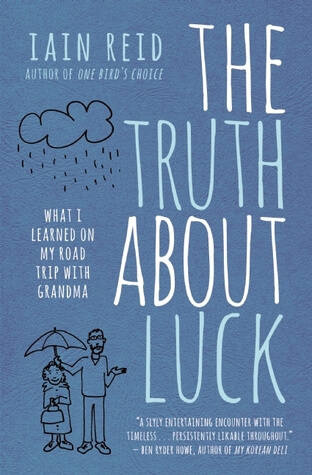

What’s a freelance writer who is a bit short on cash to do when his brother bails on their customary joint gift for Grandma’s birthday? If you’re Iain Reid, you follow said brother’s advice and give your grandmother a gift uniquely suited to you: time. The Truth about Luck is Reid’s memoir of the week he and his grandma took a staycation together. It’s an unassuming premise that unfolds into a quiet, funny, and insightful book.

“Grandma slowly brings her glass up, asking for a cheers. I clink hers with mine. ‘Here’s to stories,’ she says. ‘Old and new.’

‘And memories,’ I say.

She holds up her glass a moment longer as I take my sip. ‘Yes, she says, ‘and to not letting them go to waste.'”

– The Truth about Luck, Iain Reid

What’s a freelance writer who is a bit short on cash to do when his brother bails on their customary joint gift for Grandma’s birthday? If you’re Iain Reid, you follow said brother’s advice and give your grandmother a gift uniquely suited to you: time. The Truth about Luck is Reid’s memoir of the week he and his grandma took a staycation together. It’s an unassuming premise that unfolds into a quiet, funny, and insightful book.

Reid offers to take his 90-year-old grandmother on vacation for a week to celebrate her birthday. He doesn’t mention that due to cashflow issues, the vacation is going to take place in his apartment in Kingston, a couple of hours away from her home in Ottawa. Grandma doesn’t mind, though. In fact, she tells him that all her friends simply couldn’t believe he was doing such a nice thing for her. Reid’s guilt and neuroses that he can’t show Grandma a better time are overwhelmed by her relentless optimism and genuine pleasure at spending time with her grandson. They roadtrip together from Ottawa and over the course of the week go out for dinner, enjoying reading on rainy afternoons, take a ferry out to Wolfe Island, and find their conversation flowing more and more freely.

Continue reading “Here’s to memories: a review of The Truth about Luck by Iain Reid”