Introduction

Part 1: The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing (first half)

Part 2: Letters from Zedelghem (first half)

Part 3: Half-Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery (first half)

Part 4: The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish (first half)

Part 5: An Orison of Sonmi~451 (first half)

Part 6: Sloosha’s Crossin’ an’ Ev’rythin’ After (whole story)

Part 7: An Orison of Sonmi~451 (second half)

The Story So Far . . .

Sonmi~451‘s interview picks up exactly where it broke off, so we are thrust somewhat violently back into the narrative. Hae-Joo Im, it turns out, is a member of Union, the dissident rebel group mentioned as a threat to Unanimity in the first part of the story. Sonmi trusts him even though he lied about his ID, and goes with him before the enforcers can reach them. They meet Mr. Chang and escape in his ford, whereupon Hae-Joo and Xi-Li cut open the tips of their index fingers and extract a “tiny metallic egg”: their Souls, with which consumers of Nea So Copros are tracked, identified by name and strata, and spend dollars. As they make their escape, their car is rammed and Sonmi wonders why the feeling is familiar. Xi-Li is hit with a Unanimity phosphate fire shot, and Hae-Joo shoots him to save him the agony of that death.

They reach the conurb of Huamdonggil, which the Archivist says is an “untermensch slum” (p. 315). This, Sonmi explains, is a place of the wretched, where consumers go when they can only afford euthanasia or to be dropped into an oubliette, where migrants hide, and where crime flourishes. It is tolerated by the government because it teaches the respectable downstrata a lesson: stay in line, or end up in a place like Huamdonggil. Once there, they enter a building and wait for the arrival of Ma Arak Na, evidently a higher-up within Union’s ranks. She is addressed by Hae-Joo as “Madam” and only appears through a ceiling hatch. Mutated or perhaps the victim of a botched facescaping, she has webbed lips and “gem-warted” fingers, and it isn’t explained why she only ever peers through ceiling hatches.

Hae-Joo reports the capture of Mephi and the death of Xi-Li, and Ma Arak Na shows them into another room, where a holographic carp addresses them. It is an avatar for the secret Union general An-Kor Apis, who congratulates Sonmi on choosing her friends well and promises she may help Union change corpocratic civilization. A Soul implanter arrives to extract Sonmi’s fabricant Soul from her throat and to implant new false Souls into both her and Hae-Joo. Then it is off to the facescaper, Madam Ovid, who also seems to be a Union sympathizer and who changes Sonmi’s appearance. The Archivist asks how it is that Sonmi looks like a Sonmi now if her features were changed then. She points out that Unanimity wanted her to look like a Sonmi for her heavily publicized and broadcast trial, so they changed her back.

Hae-Joo and Sonmi travel out of the city, having a close call where they are almost discovered. They spend the night in the Hydra Nursery Corp, one of the “arks” where fabricants are grown in wombtanks. Fabricants are genomed to stay awake 19 hours a day, so after a only few hours’ rest, Sonmi watches Hae-Joo sleep and wonders which of his many aliases he is to himself when he dreams.

The next day, as they continue their journey, Sonmi asks why Union is spending such resources to protect her. Hae-Joo responds that Nea So Copros has polluted soil, poisoned rivers and air, and issues with its food supply, as the “Production Zones” in Africa and Indonesia are now more than half uninhabitable. As the wealth of the corpocracy declines, its future rests on the cheap-to-manufacture fabricants who do all of the dirty, hard, life-threatening jobs, and who die after 48 hours without government-issued Soap. Fabricants are truly a slave class, present-day Sonmi tells the Archivist, who can only be saved through revolution. The Archivist is shocked, believing that effective change can only be achieved incrementally. He asks how this massive revolution could possibly by achieved. Sonmi’s reply: “By engineering the simultaneous ascension of 6 million fabricants,” (p. 326) who would then stop doing all of the jobs necessary to keep the corpocracy running. When the Archivist doesn’t understand what difference this would make, Sonmi asks, “Who would work the factory lines? Process sewage? Feed fish farms? Xtract oil and coal?…Lift dig, pull, push?”

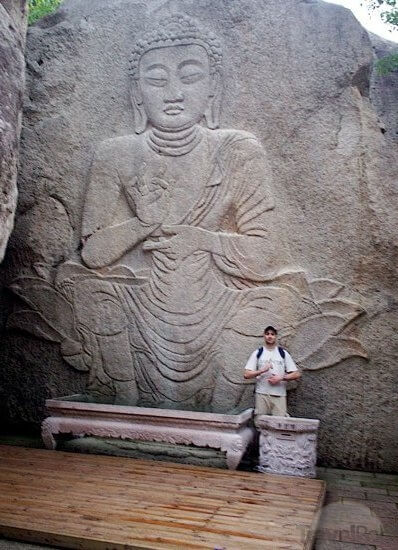

Sonmi~451’s role in all this is to be living proof that stable ascension is possible and to act as an ambassador between Union and fabricants, to turn the newly ascended into revolutionaries. She ponders this as they reach their second night’s stop, a community of people living outside of corpocracy, fending for themselves and living from the land. Hae-Joo points out a mountain across from them in the forest, which Sonmi realizes is a statue of a cross-legged giant, one hand raised. He reminds Sonmi of Timothy Cavendish, somehow. Hae-Joo tells her that he was a pre-Skirmish deity who liberated people from the cycle of birth and rebirth. The peoplw with whom they are staying live in the abbey that has occupied the land for 15 centuries, and is led by a wise Abbess. The Abbess tells Sonmi that the stone deity was known by many names that are lost, but they do know he was called Siddhartha, and that while some worshipped him as a god, he was actually a man who lived, taught about how to overcome pain, and died, “a dead man and a living ideal” (p. 332).

Sonmi and Hae-Joo leave the next day, crossing a suspension bridge where they are worried they have been discovered by a ford that blocks their path. Instead, the ford belongs to a couple who toss a “living doll” fabricant over the side to its death in the river below, the cheapest way of disposing the sentient toy their child no longer wants because it is no longer in fashion. The Archivist is surprised that Sonmi considers this an act of murder.

At last, they reach their destination, Pusan, where they settling into an apartment Hae-Joo keeps under a different alias. They are sent by General Apis to one last destination: Papa Song’s Golden Ark, which Sonmi knows from AdV footage: her Twelvestarred sisters (those fabricants who have “paid their debt” to the corp by serving faithfully for 12 years) board the Golden Ark and are taken to the fabricant retirement village of Xultation, in Hawaii. Posing as technicians, Hae-Joo and Sonmi sneak on board and hide in the gangways near the ceiling. They watch as a group of 200 Twelvestarred fabricants sing one of their sisters, a Sonmi, through the doors, on her way to the promised land. In a private room, the server is ushered into a chair where her collar will be removed. Gushing gratitude, this Sonmi doesn’t notice what Sonmi~451 does: there is only one door in and out. A helmet comes down from the ceiling over the fabricant’s head, Sonmi hears a sharp noise, and she realizes the fabricant is now dead. the helmet lifts her up out of the chair and moves the corpse along a rail in the ceiling into the next room.

Horrified, Sonmi is led along the gangway into the next part of the ark: the slaughterhouse. There is no Xultation. Twelvestarred fabricants are murdered, stripped, butchered, and turned into biomatter that supplies wombtanks, Soap, and even Papa Song products sold to consumers. The Archivist, appalled, refuses to believe that this is the case: it seems consumers believe in the existence of fabricant retirement colonies as much as fabricants themselves do. He points out that fabricant rights are guaranteed by the Beloved Chairman. Sonmi, in return, suggests that no one has ever seen a fabricant retirement village, and that Unanimity simply exterminates and recycles its slave class.

Rattled to the core, and newly resolved to fight against these injustices, Sonmi returns to the apartment with Hae-Joo, where they have joyless and “necessarily improvised” sex (p. 345). Sonmi knows that the ark, and all those like it, and the corporations and the government behind it all must be destroyed. She is installed in a villa, where she writes her Declarations, which the Archivist says “xperts” discredited as not her own writing. Sonmi claims sole authorship. And, after spending so much time in thought and writing, she also knows that as soon as her Declarations are written, Unanimity will come for her.

How could she knows this, the Archivist asks. Sonmi’s answer is simple and devastating: she has been a manipulated actor in a staged drama, from her time in Papa Song’s onward. She has been shown very specific things, including the murder of the fabricant doll, the plight of the downstrata, and her own struggles at the hands of purebloods at the University, and most especially the final sight of the slaughtership, not to create revolution for Union, but to prove Unanimity’s point. Union exists at the will of Unanimity, both to attract revolutionary types like Xi-Li and keep them in line, and to act as a “bad guy” that Unanimity can point to and blame for problems. There is no uprising, no revolution, no real Union. It is all run by Unanimity, and Sonmi was manipulated not to inspire revolution but to inspire fear. Unanimity can now use her:

“To generate the show trial of the decade. To make every last pureblood in Nea So Copros mistrustful of every last fabricant. To manufacture downstrata consent for the Juche’s new Fabrica Xpiry Act. To discredit Abolitionism. You can see, the whole conspiracy has been a resounding success.” (p. 348–9)

After figuring this out, she still went along with it because her hope is that her Declarations will somehow find a way to influence people. And she she has succeeded: by banning adherence to her writings, by teaching them as “twelve blasphemies,” the government has all but guaranteed their spread. That there will be a statewide “Vigilance Day” against fabricants who seem to be following the Declarations proves there is a need for that level of security, so Sonmi has won.

And now, Sonmi makes her last request before her date with the Litehouse: she would like to see the second half of The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish.

Some Thoughts…

Oh, this section is chilling. The double reveal, first of the real fate of fabricants, and second of the real purpose of Union, are sucker punches. While I had the sense that the true story wasn’t being told about fabricants’ fates, I wasn’t in any way expecting that Union was merely a Unanimity puppet. Does Hae-Joo know? Is his real identity that of a hardcore Unanimity man posing as a Union agent? This opposite of “bread and circuses” is Machiavellian and brilliant, using conurbs like Huamdonggil and tales of evil fabricants like Yoona~939 and Sonmi~451 as cautionary tales to keep the downstrata in line and orchestrate legislation such as the Fabricant Xpiry Act.

We see more of Sonmi’s world in this half, bringing shape to realities we have probably guessed at: Nea So Copros has been “cordonized” against the encroaching deadlands, and fabricants are used to patrol the cordons. Fabricants do the dangerous, tedious, awful jobs in this society, ones that migrants and minimum-wage workers often do in our own society, and without their enforced labour, corpocracy couldn’t exist. Fabricants seem to have been genomed not to have sexual organs, as Sonmi makes mention of stolen fabricants in Huamdonggil who “end up in brothels, made serviceable after clumsy surgery” (p. 315), along with her reference to the “necessarily improvised” sex she has with Hae-Joo. (Important, I think, that this is an act of reaffirming life and not of love. She and Hae-Joo have been co-conspirators and possibly even friends throughout, but this isn’t a love story.)

A further example of how fabricants are genomed to be workers who can’t enjoy the things consumers do: the mere taste of non-Soap food incites vomiting in Sonmi. Then again Sonmi also says she wasn’t genomed to be a revolutionary, but Hae-Joo tells her no revolutionary is. Her reluctance reminds me of the classic exchange between Frodo and Gandalf in Fellowship of the Ring:

“I wish it need not have happened in my time,” said Frodo. “So do I,” said Gandalf, “and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”(7th ed. pp. 55–56)

The Archivist accuses Sonmi of having bought into Union propaganda. Sonmi reverses the accusation: the Archivist is just as guilty of having bought into Unanimity propaganda. He is so shocked by what she says, so convinced she can’t be right, because he can only see the world through the Unanimity-taught lens of his society and upbringing.

Mitchell plays with a prevalent sci-fi theme here as well, the idea that nature will survive and find news way to grow and surpass human ruin, as we see with the “once genomed moths” whose “wings’ logos had mutated over generations into a chance syllabary, a small victory of nature over corpocracy” (p. 328). We’ve already seen this world’s future. We know that even though much of it is deadlanded, the forests in Hawaii have overtaken the Old-Un buildings.

And as mentioned in the first half of the Sonmi readalong, this is the kind of science fiction that holds up a mirror to today’s society, reflecting us in its story. The idea of Sonmi’s “trial of the century” is so very close to our morbid fascination with reality TV and celebritized trials. Of course Sonmi had to look like a Sonmi, had to be physically prepared to incite the strongest possible reaction from the viewing public. It’s not actually about justice but about conveying the message Unanimity wants to convey. Is that so different from a nation tuning in to hang on every detail Nancy Grace can grind out of the “Tot Mom” trial? And as Sonmi says to the Archivist, the Abbess’s colonists are happy to entertain themselves: “Consumers cannot xist without 3-D and AdV, but humans once did and still can” (p. 330). Not too far off our screen-obsessed culture today.

The overarching predator/prey theme continues to play out here on multiple levels: Unanimity preys upon consumers and upon fabricants. Fabricants, in fact, are quite literally physical prey, being killed and consumed by Unanimity. The “Production Zones” in other parts of the world feed the predator corpocracy. And at an individual level, Sonmi is set up and preyed upon by the government in order to keep the untermensch and fabricant classes down. Mitchell is also subtly telling us that Sonmi’s views are the correct ones, that it doesn’t matter if someone is born in a “wombtank or a womb,” they are human beings: after all, the reincarnated soul we are following was born as a fabricant. There are strong parallels between Sonmi’s world and Adam Ewing’s, similar enslavement and Abolitionist movements, similar arguments for and against acknowledging slaves as human beings.

Once again, we’re looking at a fascinating evolution from religion to corpocracy: while religion doesn’t seem to exist as we know it, the technology known as the “eternal Soul” is what tracks a person’s dollars and their place in society. The idea of a deity still exists, but most of what is known about the Buddha is lost, and, one would imagine, other religious figures and doctrines as well. This recalls what Zachry says about Church in “Sloosha’s Crossin'”: the idea of a lost deity, “an ancient god was worshiped, but the knowin’ of that god was lost in the Fall” (p. 285). The connection is drawn here between the Buddha’s changing nature between a learned, dead man and a deity, and Sonmi’s own future fate: to be worshipped as a god by Zachry’s people when the reality of her life is all but lost.

A side note on the idea of lost knowledge: I wonder at the naming of “Madam Ovid” the facescaper: this is clearly a nod to Ovid, who wrote Metamorphoses, because she metamorphoses her clients into new shapes. Is this David Mitchell having a bit of fun, or is this an echo of an old name that has persisted into this future? Or both? Certainly Sonmi is aware of writings of that time, as she makes reference to Nero and Seneca at the end of her tale, but she has also read more widely than most people in her society.

Many other points of connection exist here. Now that we’re moving back through the stories, we have a sense of who all of the players and what all of the settings are, which means we’re bringing more knowledge and insight to this second half of the book. Sonmi’s strange reaction to her car being rammed, “the final drop shook free an earlier memory of blackness, inertia, gravity, of being trapped in another ford. Where as it? Who was it?” (p. 314) seems to be the echo of the last place we left Luisa Rey, and definitely reinforces the theme of one soul being reborn into many different times and situations. This also lends credence to the idea that the Luisa Rey Mystery, “airport novel” that seems to be just fiction sent to Cavendish, might indeed be based upon real events. Looking forward in time, Sonmi’s Declarations must be what is informing the religion in Zachry’s valley, must be those writings that the Abbess still has on paper and still consults, without knowing or understanding where they came from.

The general in charge, Apis, is an echo of “Aunt Bees” in “Sloosha’s Crossin’,” and we have a wise Abbess figure in both narratives. The Hydra facility where Sonmi and Hae-Joo hide is another Luisa Rey reference, recalling the Hydra facility Luisa and Sixsmith need to shut down. Xultation’s location on Hawaii calls forward to Ha-Why in “Sloosha’s Crossin’,” and back to the ocean that Adam Ewing spends so much time crossing. And even Cavendish’s hilarious parting shout “Soylent Green is made of people” (p. 177) as he tries to escape Aurora House takes on a grim reality in this tale: truly, Soap and fabricants and Papa Song’s delicious meals are made of people. Funny that the “barbaric” Maori are supposed by the white men in Adam Ewing’s time to be cannibals, and the so-called highly civilized people of Unanimity really are cannibals. Delicious (if you’ll pardon the pun) irony.

At a circus in Pusan, a man with a megaphone invites the crowd to come see “Madame Matryoshka and Her Pregnant Embryo,” a nod both backward to Vyvyan Ayrs’s Matryoshka Doll Variations in part 2 and to the stacking-doll structure of the book itself. This intertextual book’s parts play upon and recall and echo each other. This is such a big part of the book’s genius and appeal: the book references its own structure in a way that is is so meta and so unsettling. Mitchell is reminding us that we are reading a fictional work, and that within the confines of that fictional work, we are reading six narratives that may or may not be fictional themselves. It’s enough to make you sit back and take a deep breath or two before plunging back in.

And, of course, the end of Sonmi~451’s tale delivers us backward into the second half of Timothy Cavendish’s.

What do you think of the end of Sonmi’s tale? Were you as shocked as I was about Union? Do you see parallels between Sonmi’s world and our own? Do you think Unanimity’s strategy to manipulate Sonmi is sound (if evil)? Share your thoughts on the second half of Sonmi~51’s orison.

You might also like:

Reblogged this on Jottings.

I still have a hard time with believing the end of the Sonmi story. It isn’t plausible, from my view, that Unanimity wouldn’t foresee the reaction to the Sonmi story and understand the viral-risk of her point of view catching on. That’s PR 101 since the 1980’s at least, thus isn’t believable for a story set in a future, more-developed corpocracy. It would divide the consumers at best, unnecessarily bring about ascended slaves to the Unanimity plot (in a bad pulp authorship kind of way), and we don’t get to see any of this action anyway, just learning that nothing worked out later. In fact, Prescients must be ascended slaves, I’d think, right? Is Unanimity double-crossing Execs?(interesting, but no) It’s all too flimsy to count on. Don’t like this episode’s ending.

I assumed that there was something odd going on from the point at which we were told that the servers at the dinery were being fed a different formulation of SOAP ‘with the cooperation of the management’. After the first scandal, they’d have immediately changed it, so as not to have another. I wondered whether the Seer was blackmailed or bribed to be in on it.

This may be premature as I have only just finished reading Sonmi’s part 2, but I think Mitchell explains/foreshadows Unanimity’s plan for Somni through Cavendish’s words on the last page of his part 1 where he says:

“Slavers welcome the odd rebel to dress down before the others. In all the prison literature I’ve read, from The Gulag Archipelago to An Evil Cradling to Knuckle Sandwich, rights must be horse-traded and accrued with cunning. Prisoner resistance merely justifies an ever-fiercer imprisonment in the minds of the imprisoners.”

Hi there! I think your analysis for the different fragments of the story is fantastic. I just started reading the book after watching the movie (repetitively!) and I have so many, many questions. What’s great about the book is that Mitchell has created all these open-ended answers by giving us so much information about the human condition and a specific aspect of it -predacity. He tackles so many social and political issues. It’s an astounding piece of work. I’m enjoying reading through your analysis for The Orison of Sonmi 451 and the other fragment that really fascinates me is the Frobisher/Sixsmith story. I wanted to ask you if you thought there was a chance (even after the narrative ends and we close the book) – just hypothetically- that he and Sixsmith would ever meet again as Frobisher wished in his letter.

I somehow feel that in committing suicide, he made sure that he and Frobisher would never meet again.

Thanks so much for taking the time to put all of this on the interwebs! I can’t get the movie out of my head and I love that I found your analyses.

I wondered that to, but I think the book differs in this notion from the movie. In the movie you get the impression that the Comet Soul and Sixsmith’s are destined to meet again in another life. From the book I gathered that Frobisher’s meaning wasn’t that. Instead, it was that the exact same scenario would occur again. He says they will meet again in the sense that he will relive that same life. He’ll be born again in the same life, thirteen years later he’ll meet Sixsmith the same way, ten years later he’ll be killing himself again. They are a “song” of sorts the “Old One” will keep playing for an “eternity of eternities.” In short, I think he meant that while his soul may come back, and he may encounter Sixmith’s again, the point is that they had each other for those ten years, and that was a beautiful thing.

Tragic, yet beautiful in its own way.

A reviewer on Imdb linked me this website, and I’m now slowly reading through your readalong and the comments. So many interesting opinions. Thank you so much for your efforts in explaining the connections! I started reading the book the day after watching the movie and I’ve now just finished reading Cavendish 2. Sonmi’s section is my favourite and I, too, believe that the ending is very ambiguous.

I am loving this book. I have hopes that it will rank among my favorites once I’m done. Sonmi-451’s story has interested me the most of all the stories. In part because it’s easy to read, unlike some other sections, but mostly because I love a good future dystopia. Having just finished it, like many of you, I feel unsettled. I would really like to feel resolved about this story, but I don’t. Some questions are (there is some overlap with comments above):

1) Why would Unanimity try to enact the “Fabricant Xpiry Act”? The entire social structure is built upon the backs of these fabricated slaves. Are they planing on replacing the existing fabricants with new, more “reliable”, models?

2) The sex scene came out of nowhere. Were there romantic embers being kindled the whole time that I missed? It didn’t fit with her narrative.

3) After visiting the massacre ship, it’s like Sonmi-451 presses fast forward through to the end of her story. Why the hurrying-up at the end? Especially when she reveals the biggest plot twist. Not a time in the story for skipping over details.

4) Why would an all-powerful regime orchestrate a very articulate and emotive rebuttal to their principals, and then give everyone a copy? Here’s a convincing manifesto against our doctrine, read it!

5) Such a heinous secret as the fabricants being butchered like animals, being used as their own food source, and as an ingredient in “pureblood” food can be witnessed by someone showing-up and saying they need to perform some maintenance? Seriously? There wouldn’t be better security measures in place guarding this national secret? I know this was asked by the archivist too, but the questions still stands–if there really is a rebellion, and it’s so easy to get on those ships, why has the truth not been exposed to the public?

I’d appreciate anyone taking the time to give me their opinionsc, thank you!

One more question, I just remembered:

How is it that Mr. Chang shows up right when Sonmi-451 happens upon the overdosed seer? I never got how the fact that he was there too wasn’t super weird/random/convenient.

Thanks!

Some really interesting commentary here. I’d like to propose an alternative interpretation of the final pages: Sonmi was lying about Union and her revolutionary companions being tools of Unanimity.

One of the themes of Cloud Atlas is Truth and how the Truth we’re perceiving in the book depends on the narrator. Certain things we know are true, and these are events that are referenced in multiple stories–for example, we know that the Delcarations were published and they were generally credited to Sonmi (by Zachry’s time). Specifically with Sonmi, I think we are slightly manipulated towards buying into her truth. Part of this stems from the fact that the story of Sonmi we are reading follows her ascension and enlightenment, and how she seems “pure” because she is learning everything from multiple angles without having any previous biases. Keep in mind that this is how she is presenting herself to us, and the first half of her story ends when she’s pretty much completed the “pure” portion of her ascension (before Hae Joo reveals himself to be Union). Then, we are thrust into Sloosha’s Crossin, where Sonmi is regarded as a Goddess and a force of “good” in the face of Old Georgie’s “evil”. This exact setup really makes us believe in Sonmi and believe in her Truth.

That sets us up for the second half. The second half of her story is when she really shines an ugly light on Unanimity and corpocracy. Is it a coincidence that this part of her story is presented to us once we’ve completely bought in to her Truth? Then at the end she starts explaining that there were “cracks” that should have been spotted, and explains how Seer Kwon’s part was too coincidental, etc.

Finally, she tells us that the entire story we bought into was a theatrical production by Unanimity, and explains why. My interpretation is that she deliberately told her story in this way, and revealed this at the end, because she knew the affect it would have on her future audience. How did it make you feel reading it? It was a punch in the gut, and you probably thought about how evil Unanimity is and also felt betrayed by Mephi and Hae Joo. How would this have affected an audience watching the Orison? They would have felt angered, enraged, saddened, betrayed, emboldened. This is EXACTLY what Sonmi (and any revolutionary movement) would want the people to feel. So, my conclusion here is that this WASN’T a big setup by Unanimity, but that Sonmi and her fellow revolutionaries decided to present it that way to exponentially increase the emotional reaction of the population. I think that she’s telling the truth when she says that she was arrested the day of publishing her Declarations and that this was the “logical next step” or whatever she says, but that it’s the “logical next step” in the revolutionaries’ plans to make her a martyr rather than the next step in Unanimity’s plans to control the pureblood.

Reasons from the text that may support this interpretation:

At the end when she says “haven’t you spotted the cracks?”, to me she is asking a legitimate question and that she has intentionally created cracks in the story or left them in, but they’re not the cracks she mentions. The cracks I see are the ones where the real truth shines through the thin veil she places over it at the end.

1) During the very first interaction between Sonmi and the Archivist, the Archivist tells her that “[her] version of the truth is what matters” to which she replies “that’s the only thing that’s ever mattered to me”, foreshadowing some distortion of the truth by her and others.

2) She says at the beginning that she was dreaming of Hae Joo before her interview. If he really was a devout Unanimity man and betrayed her so terribly, would she still be thinking about him that way?

3) She says that when she finished her Declarations, she gave them to Hae Joo and he or his organization somehow got them published. Why would Unanimity want to publish them? Or if they wanted to publish something to make people hate fabricants, why wouldn’t they just throw out what she wrote and replace it with things like “fabricants must rise to destroy purebloods”?

4) The Archivist knows details about the trial (what she looked like, etc.) and seems absolutely surprised by Sonmi’s exposition of Union and its purpose. There are two explanations: either the betrayal of Hae Joo/Mephi didn’t come up at the trial because Unanimity wanted to suppress it (either by not allowing testimony or by censoring that testimony), or it simply isn’t true and is a fabrication of Sonmi and the resistance movement (and so there was no active effort to suppress it by Unanimity). If it was just being suppressed, why would Unanimity then allow Sonmi’s Orison to exist, rather than destroying it to keep hiding the truth?

5) This interpretation would make other things in the story make a whole lot more sense, rather than everything just being an extremely elaborate ruse by Unanimity to achieve a seemingly self-destructive and shortsighted goal.

The character development of some of the non-Sonmi characters, such as Hae Joo and Mephi, also makes it hard for me to believe that they were really “in on it” the whole time. I think Sonmi shows them to us that way as a tribute to them, knowing that she’s casting them as betrayers for the rest of history but that they were really sacrificing their names throughout history to help Sonmi achieve the final catalyzing step in the revolutionary process.

I’d be interested to hear if I’ve convinced anyone!

You’ve convinced me! Thank you for this!!

I mean it’s hard to say – the end of Sonmi’s story is so shocking, particularly the betrayals that it says such desolate things about human nature, let alone society. Thus your first reaction is to not want to believe it. You’ve given me reason to think it could be otherwise which makes me feel happy before I even analyse it! But, it does also make sense to me!

For, when you think about this section further, it simply doesn’t seem to make sense for Unanimity to have done such a thing. Obviously they would manipulate what was seen of Sonmi, but in order to achieve their aims.. what even really has Sonmi done that will make people fear fabricants?!?!

`

Surely people can only treat fabricants as they do as they can see them as not human as that’s how they are genomes and kept as much as possible due to soap. Surely anything that shows fabricants as actually human in their thinking, even if details such as what happens to 12 starred fabricants never make it to anyone’s ears… it’s going to make people look and is thus promoting Abolishinism. ???

This would make sense of it. It also seems to make sense that Sonmi doesn’t go into detail of her final times – writing her Declatations… and possibly formulating/discussing such a plan with Hae-Joo – to distribute them and for her inevitable end.

Should have checked that before I posted it! Look before you hit send!! Too much of a rush me!!! Sorry!! In any case, I reckon I’ll choose to believe this. Could ramble on more, but I shall spare you as I tend to ramble in circles!!

Can’t stop thinking about this! I think it’s affected me more as I read the book back last October & the film only recently came out in my country. It was probably perfect timing in a way as I recalled the book in enough detail & had also forgotten enough to not make too many of the shortenings of the story bothersome to me (a few things grated but I truly adored the film – I like that it’s both more optimistic in a way, yet in another sense it keeps some of the exact same tone) Anyway, I digress. Rereading the novel now (just finished Timothy Cavendish part 2) & I discovered I’d utterly forgotten how Sonmi ended. In the film I was in fact a little surprised how forefront a character Hae-Joo was as though he’s made of more than one character from the book, I think I had blanked him entirely, offended at the betrayal.

Anyway, what I wanted to say on this note is – Union’s supposed original aim was for Sonmi to essentially lead the revolution of Fabricants who they would ascend. With her Declarations coming out thus though, obviously depending on exactly what consumers know, my personal view would be that surely rather than making consumers fear Fabricants it would gain more sympathisers and thus add many consumers to the fabricant’s side for such a revolution.

It all seems so right.

This said, the impact of everyone who helped Sonmi whatsoever betraying her is incredibly powerful in the novel. But then again, that’d be a great way to incite revolution. I know I’m talking to myself and merely repeating what’s already been said. And I’m aware that most stories in the novel centre around how utterly awful and self-serving humans are to one another, so I suppose it’s silly to think of such a positive alternate, but…

Some of us still listening. 😉

haha, it’s good to know I’m not merely rabbiting at myself (it wouldn’t be the first time, hee!)… although for all the sense I make I’m sure I may as well be!! 😉

I’m so curious now though if this is a serious implication in this tale as it really does make sense to me, particularly given the juxtaposition of the relative detail in terms of character description as well as plot within the tale with the way it’s whizzed through at the end…

Though I do kind of like the utter dismal-ity of how it naturally seems. Still, I wonder!!

Anyway, I promise I will shut up now!!!

I don’t think Melphi and Hae Joo were necessarily “in on it”, but perhaps they were puppets who truly thought that Union was real, but were really unknowingly following Unanimity’s orders.

I think that Sean has the right interpretation here.

When I finished this part of the book, I could not help but think two things :

– It makes no sens for the Uninamity to go through such a complicated plan when they have the cards to stage the same trial out of thin air (argument well developed above, I won’t go further).

– Jesus is nothing without Judas.

To explain myself on this one :

Sonmi=> Son Me => The Son is Me.

Even her name says she is the Messiah. A Jesus who was “Judased”.

Without Judas to sell him away, Jesus would have only been a weird wise guy and quickly forgotten. By being (supposedly) betrayed by the only people she trusted Sonmi becomes a true martyr, and her memory can live on to make her a goddess and not a mere forgettable political figure.

Her Declaration alone would have made her into Abraham Lincoln. The twist ending of her Orizon made her into Jesus.

The long lost “Judas Gospel” says that Judas knew there was a need for a traitor and that Jesus entrusted him with being hated and becoming the epitome of betrayal. Whether this Gospel says truth or not, it is an interesting view.

I can imagine people as aware of the ugly truths as Hae-Joo Im and Boardman Mephi accepting this role as necessary, and I cannot see them deciding to help the Unanimity survive, especially using sheer sadism.

Their knowledge of the truth of the system and of human nature implies that they (and many others in the Union) know enough to see that the Corpocracy is doomed and that this “conspiracy” would only quicken it’s end.

So, from a “psychological” standpoint, I can imagine the Union sacrificing their memory and making themselves Judases forever for the sake of Humanity. But I think it impossible that anyone would look at the abyss straight in the eyes for a long time and then say…. “Okay I’ll help build a pink fence around that, I’m sure it will make things better”.

Thank you Sean for making those lingering doubts into steel beliefs !

David Mitchell REALLY messed with us on this one.

🙂

Really enjoying this read along. Thanks for your comments on Jesus/Judas. I have always thought that Judas has had bad press all these years – someone had to do “that job” and it just happened to be him.

You’re welcome !

Every great hero needs a great betrayal to become immortal, I think that the Union is very aware of that.

One more thing I thought of : the customers don’t know about the slaughterhouse. It is because they think the fabricant are very well treated that things can continue as they are.

Most of the customers also don’t know that their civilization is on the verge of a catastrophe (the “rogue genes” contaminating everything, the dead-lands growing super-fast, the possibility to live differently…)

Then why would Unanimity allow Sonmi to speak to an archivist with what she knew? It would make more sens that they had no idea she knew any of that, maybe they did not realize the extent of her “ascension” and did not know that she was very intelligent and able to lie and hide things…

I think that the Union did not just prepare a sob-story of betrayal and all-powerful Unanimity, Sonmi also hid things during her trial so that she would be thought ignorant enough to speak to an archivist.

As for the fact that she knew when she would be taken : the Union has agents even in the higher ranks of society, they would know if someone is coming to get them, or they could have protected Sonmi until she finished her Declarations and leaked her location after that, so that it would really look like a Unanimity plot.

Thank you for this great read-along and all the comments, it makes me think even deeper about an already very deep book !

Hello and greetings, fellow Atlas aficionados!

I, like so many others that have found your readalong, truly appreciate your insights as well those of the many who comment here. Thanks to EVERYONE for contributing to the discovery and enjoyment of this masterpiece. So many great additions to your commentary in the discussion board here, I would be honored to throw in my two cents.

I found it interesting that, having received her new “Soul,” (which, incidentally, can also sound like Seoul) Sonmi~451 was renamed Yun-Ah Yoo. It happens that the esteemed Abbess was called Ms. Yoo. Also, said aloud, Yun-Ah bears a striking resemblance to Yoona, the first fabricant to display signs of ascension. Does this indicate that parts of Yoona~939 may have been reborn in the “new” Sonmi? I started reading all names this way and the only other one that struck me was the Union leader An Kor Apis. I read this in two ways: my first thought was like the anchor of a ship, which in some ways has been a theme in the book; the second relationship is that of the Cambodian city Angkor Wat. Angkor Wat was a temple built by a king in the 12th century. Originally devoted to Hinduism, it was later reborn as a monument to honor Vishnu, then again later converted to a Buddhist site (thanks wikipedia). Apis, for what it’s worth, is an Egyptian deity represented by a horned bull.

Connected? Maybe. Important to the storyline? Probably not. Indicative of Mitchell’s literary brilliance? Most certainly. Shared here to inspire others to dig deeper into this Matryoshka doll of a tale and report their findings for the benefit and enjoyment of others.

Thanks, and keep up the great work!

Thank you very much for this readalong, it is brilliant! I love this book and I agree it is worth rereading at least a few times.

I’ve always been interested in symbols and in this book they are abundant. Take An Kor Apis a carp for example. I noticed quite a few fish symbols planted throughout the whole book. What do you make of this? Can it be viewed as a symbol of sacrifice?

Wow, so much here. Having watched the movie first, I was utterly shocked by Somni’s insight into the true nature of Union, and the loyalties of Hae-Joo. Honestly, it was a pleasant surprise, given that much of the dramatic tension is gone from things like the fates of Luisa Rey and Robert Frobischer. (Or maybe I’ll be somewhat surprised again.)

Upon first reading, I didn’t think Sonmi was shocked or informed externally of Unanimity/Union duplicity. It seemed she’d intuited or deduced it herself: for instance, knowing that, upon finishing her declarations, she would immediately be arrested. This shows another parallel between the stories of Sonmi and of Jesus, in that she knew of her betrayal (“judasing”) and knowingly went to her own martyrdom.

The purposes of Juche Unanimity in creating Union as a “foil” and allowing Sonmi to Ascend in order to then conduct a show trial may be shortsighted, but totalitarian regimes in real life are often shortsighted (so are democracies). We have examples of regimes demonizing a “rot among us” both literary (such as the Brotherhood in Orwell’s 1984) and real-life (Jews under the Nazis). Unanimity even uses the the slave-class Fabricants and the fear of their uprising much the way U.S. Southern aristocrats manipulated poor whites with fears of an African slave uprising.

I can’t say this is my favorite section yet, having not quite finished the book. But it’s shaping up to be.

The ending of this section continues to bug me, even moreso because I love this book so very much. Here is a letter I wrote to David Mtchell’s publicist on the matter:

“Jynne,

I want to thank you for helping Mr. Mitchell, as Cloud Atlas is perhaps my favorite book I’ve ever read (most certainly my favorite contemporary book). If you get the chacne, please send him my most rapturous gratitude; I have a signed copy of the book from his visit at “Book Soup”.

I would request that you also ask him one question, however… this has been irking me for a while and after rereading the section, I still cannot decipher any practicality to what I’m interpreting: why would the government, or “Unanimity”, create this whole entire plan for Somni when their secrets are already hidden from the public as is? Why would you ever want to purposely expose the ghettos and brooding sicknesses of Huamdonggil or the massacres of the fabricants? And why would they insist on having her not only witness it, but create an everlasting documentation of it all for the whole world to recount? Why did Hae-Joo allow her to create this Declaration? How could the leaking of this document serve any benefit to the tyrannical government’s already implemented and seemingly impervious regime? If simply to repudiate any claims of an uprising, what are their worries given that Somni said the Union was not interested in a revolution in the first place? Even so, exposing their own debaucheries to the world through a labyrinth of orchestrated mayhem seems counter productive, frankly. If it was to merely reiterate the power they already have over their jurisdiction, why not reveal that the whole thing was a setup then? If purely for intimidation purposes, knowing the truth is a whole lot more imposing to me. If their intentions were to create an enemy, a “terrorist” group if you will that will allot them even more power, why would you want to make them look as justified and honorable as this adventure and the seedy factions it’s fighting against seem to prove?

Please, please, please… I would love to have some clarification on this. Any. Please. It’s seriously bugging me because every word in this book is so goddamn genius that I break down and ball like a baby with every read, so I feel as if there has to be a greater sense of closure and explanation for an ending that seems so discursive to me…

Please, please, please, I beg of you, anything will help. Thank you so much for your time, and thank you to Mr. Mitchell for changing my life.

Cordially,

James Mills”

Maybe you guys can help me with this…

I think Hae Joo was in on it. On p347 Sonmi says ” I knew we would never meet again and maybe he knew that I knew.” Maybe he was sympathetic to her pureness and felt something for her explaining the love making. I do find it hard to believe that she came to a sudden realization because she was not prone to these things throughout the story. I do wish that we had learned the “declarations” and maybe she didn’t even write them, but knew the picture she had to paint if there was a hope of revolution.

First of all high five for drawing a Lord of the Rings comparison!

I also found the second half on this story incredibly chilling. The fate of the fabricants really pulled at my heart strings. As did the scene where the couple throws the living dolls over the bridge. There were actually quite a few scenes that elicited a strong emotional reaction from me – ranging from happiness, sadness, guilt and anger. In particular I remember been incredibly enraged with the Archivist when he argued against Sonmi and his words just seemed like party-line nonsense. At the same time it also made me incredibly sad, because that same kind of buying into to whatever is easiest or most convenient is something we see today

First off, thanks for this read along. It helped change my perspective on a couple parts of the book that I wasn’t exactly looking forward to reading, i.e. Sloosha Crossing. It has made me appreciate and in turn dig deeper into Cloud Atlas.

For me, Sonmi 451 is such a great part of the book because of how closely it predicts a future society that we may all have to one day endure. I wonder about Mitchell’s feeling regarding the current trends of modern society as well as the specific examples he is basing some of his material off of.

A couple of parts that “clicked” for me and they’re modern day counterparts:

– The chips or “souls” that reside in an individual’s index finger = RFID chips for humans

– The Union being a creation of the Corpocracy and how it’s used impose agendas and persuade the masses = “terrorism” in America and the subsequent control and influence it affords the government.

I also thought about the concept of “slippery slope” and how it applies to the lives of the fabricants. In part 1 of Sonmi, she is watching the Clavendish film and says, “the only fabricants were sickly livestock.”

I believe this is a reference to the livestock that are currently being cloned and sold as meat in today’s grocery stores. Most of us don’t see the life of a cow as very valuable when compared to that of a human. The same mentality is held in Somni’s time about fabricants and I think Mitchell is showing us the plausibility of such a state of affairs. Obviously the jump from cows being cloned and humans being cloned won’t happen overnight, but though incremental steps such a change can occur without people noticing.

One thing that’s particularly tragic about the Fall is that the Fabricants would be the first victims of it. They’re utterly dependent on society working correctly to produce the necessary Soap for them. If something disrupted that, most of them would be dead in mere days if they don’t have stockpile of it or ways to make it.

Fabricant’s fates were always sealed…remember the old Michael Bay movie ‘The Island’ ?

What excellent analysis and insight into this part of the book. I loved this story and your comments have helped me see things I didn’t pick up as I was reading. Looking forward to next week.

Thank you! This is my favourite of the six. It’s such fun to take the opportunity to really stop and think about a book in-depth this way…and I love hearing what other people have to say, picking up on all the things I missed in my own readings.

I love this chapter – it’s easily my favorite section in the entire book. Sonmi is, in many ways, the most enlightened and self-aware character, at least until we come to Adam Ewing Part 2. She’s aware of predation, aware of its roots, and even ultimately aware and willing to do what must be done in order to try and stop it. Even Zach’ry (a close contender) blames external things like Old Georgie and the like for some of the decisions he made (although in fairness, he’s limited in his knowledge and education).

Of course, like Cavendish and Zach’ry, I suspect she’s polished her story over time (including at her own trial). She doesn’t say how she became aware that Mephi and Hae-Joo were certainly provocateurs of Unanimity, but it’s certainly possible that it happened when they testified at her trial. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if she actually was shocked at the time.

She also gets some of the best lines in the book, but I digress.

I think he did. There was a line by Mephi in Sonmi Part One at some point where he talks about how revolutionaries make some of the most devoted Unanimity agents, but I can’t find it – assuming it was actually there.

It wouldn’t be surprising. Extremists tend to swing from one political extreme to the other when they change their opinions – from hard-left to hard-right, or in Hae-Joo’s case possibly from wannabe revolutionary to devoted Unanimity agent.

Good point. I can think of some other parallels as well.

I can’t go into detail without spoiling Adam Ewing Part 2, but there’s a part where a certain bad character shoves the naked truth of Britain’s predatory behavior in the face of a “holier than thou”, oh-so-benign imperialist fancying how it might be mercy to exterminate the “savages” since they were doomed anyways. Naturally, having that truth put to him directly repulses him, but he denies it (Adam Ewing, though . . . )

I think there might be a parallel there with how Unanimity’s scheme back-fired. Think about the slaughterhouses for “past date” Fabricants. Media no doubt censors information about Xultation, but that still wouldn’t stop information about it from spreading if people were genuinely curious and putting two-and-two together about the missing retirement villages of Fabricants. What ultimately would make it work would be the fact that it happens largely out of sight, so the Purebloods can get apathetic about it and accept the lies about Xultation at face value.

But with the Sonmi plot, the show trial, the “Fabricant Xpiry Act”, and the Declarations, the Juche blatantly exposed its predatory nature as it is, as well as the fact that the Fabricants are slaves with nothing but euthanasia and recycling to reward them. Considering the Archivist’s reaction, that would be horrifying, leading to further discontent and anger in the downstrata . . . in turn requiring greater repression by Unanimity, and deepening the tensions in the slums.

In other words, the Juche turned their own country into a ticking time bomb of mounting pressure and discontent from below. Before Sonmi-451, they seemed relatively stable even if the looming environmental collapse and deteriorating status of the downstrata purebloods meant that Nea So Copros was going to decline in the long term. After her, though, they basically seeded their own revolution – and since Nea So Copros was becoming more and more of a “house of cards” due to the expanding deadlands, any minor damage to its structure quickly cascaded into full-blown collapse.

Phew! I’m sorry my reply ended up being so long. I’m going to go over the chapter a third time, and then I’ll be back for more.

Sorry, had to add this-

I wondered at first why Unanimity was deliberately introducing ascension to Fabricants on a larger scale, when it held the potential for them to rebel. It makes sense, though, since the grand scheme of the Juche and Xecs to “dissolve the downstrata” depends on Fabricants being able to not only do the rote-learning manual labor jobs, but also jobs like Boom Rooks.

Re-reading this chapter also had its share of fore-head slapping “duh!” moments. For example, I actually didn’t grasp the significance of the resistance being called “Union”, but it’s obvious now – a corpocracy would be afraid of organized labor and unionization, enough to make them the devil long after they’d been completely crushed.

HI Brett. I’m on my way out of town and away from internet for a week–I just wanted to say thank you for the comments and I will read and reply next week upon my return. I’ve got a bunch I want to say in response and don’t want to rush. So 🙂 Thanks, and talk to you next week!

Sonmi’s is my favourite of the six, too. What I love about the second half is how we see the layers behind the layers behind the layers that only intimated about in the first half: this is, in fact, succeeding in showing double-crosses and tragic reveals in a way that the Luisa Rey second half utterly (and deliberately, by Mitchell) fails to do.

Excellent point about Mephi and Hae-Joo testifying against her. You’re right, we’re only hearing her story from her polished retelling of it. Can you imagine the intense betrayal she must have felt if that’s how it went down? Truly, we’re seeing a horrible and cold side of humanity here. And you’re right, Sonmi does, in the very long run, win, because the Juche have done this all wrong. the Archivist’s character is a beautiful way of showing how Souled people will react, first with horror, then with growing understanding…and who knows where that leads? We don’t see how Sonmi is elevated to the status of a deity by Zachry’s time, but certainly she must have been upheld by a great number of people as a martyr, and as a savior.

Re: Union, I also love that “Union” and “Unanimity” sound like similar concepts, though they appear to be antithetical to one another.

And we’ll talk more about Adam Ewing in a few sections 😉

I think she was deliberately preparing an account to be recorded before her death. One of the earliest points she makes in Sonmi Part 1 is that every prison has jailors and walls through which information and news pass. It’s quite possible that she believed that her Declarations would generate enough sympathy so that eventually some curious and sympathetic person with archives access would leak her Orison and its contents to the public. Once that happened, it likely only added to her deification.

I can’t really tell where she’s omitting information, not like how I think Cavendish is playing around and possibly inserting fictional events to make his story more filmable. Considering her argument that “truth is singular, and versions are mistruths”, I wouldn’t be surprised if she believes she’s telling the true events as they went down, even if she retroactively interprets then with her “present” mentality and knowledge (and skips over a lot, like the extended period when she was writing her Declarations and consulting a bunch of people in the process).

It’s a sign of how well written the character is that we’re able to discuss her motivations and what she would be “thinking” and planning off-screen, even though she’s a fictional character. It’s like everything I’ve ever read about how characters develop a life of their own in the hands of their authors.

I would agree that she’s telling the truth as she sees it: she’s not deliberately changing events like we suspect of Timbo, or even mythologizing like Zachry (though I think it’s closer to mythologizing)…but she is definitely presenting her truth in a specific way. She could, for example, from the start explained to the archivist whose side Hae-Joo was really on, or that she had met another ascended fabricant in Wing~027. Instead she builds her story into a reveal, leaving her future listeners feeling shocked and betrayed on her behalf. She’s molded her truth into the most impacting story she can, in order to make a last impression on those who hear it, and, she hopes, share it.

I am struck over and over by Mitchell’s genius. Sonmi is so fully realized a character that, as you say, it’s so easy to talk about what she was likely doing “off camera.” I’m sure you’re noticing in your third readthrough things you didn’t notice in your second, as I in my second am picking up a ton more than I noticed and put together the first time around.

Thanks for bringing to light the same questions as I had with the Sonmi 451 story which were 1.) Why would Unanimity expose their evils just for a Reality Show 2.) Why would Unanimity ascend their own Fabriciants (which would bring severe questions of ethics into play, feeding the flames of Abolitionists).

Your answers are also persuasive. However, I remain unconvinced of the soundness of Unanimity’s scare tactic as you describe it. Because, there is a catch in using the method of Fabricant ascension as a scare tactic against the downstrata. The catch is, once Fabricants are ascended to the level of sentient beings no different than ‘purebloods’ (and it’s revealed to the public) then Unanimity would be forced to give them the same rights to freedom, that is, Fabricants can no longer be born into labor. (or else rights activists will riot, and Unaminity would loose respect and legitimacy as rulers) This defeats the purpose of Fabricants. And thus you are back to square one, who will scare the Fabricants into working hard? It becomes an infinite regression.

For me, Sonmi’s trial didn’t so much conjure up reality TV as it did the Stalinist show trials of the ’30s and ’40s. Then again, I don’t watch Nancy Grace.

Thanks for these wonderful essays – Cloud Atlas is one of my favorite books, and it’s such a pleasure to read someone else’s appreciation of it.

Oh, really good point! I was thinking of how this book written in 2004 is already resonating with the way things like reality tv and sensationalist trials are occurring now in 2012, and hadn’t thought backward about historical examples. Which, of course, plays into the theme of history repeating. Of course the totalitarian corpocracy would stage a show trial similar to earlier totalitarian regimes. Thanks for this!

And thanks for reading and commenting 🙂 I’m so pleased you’re enjoying the readlong.