Introduction

Part 1: The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing (first half)

Part 2: Letters from Zedelghem (first half)

Part 3: Half-Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery (first half)

Part 4: The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish (first half)

Part 5: An Orison of Sonmi~451 (first half)

The Story So Far . . .

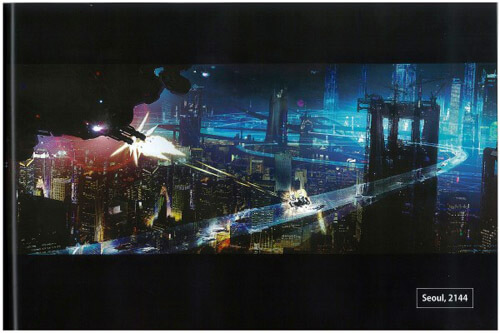

Of all the stories in Cloud Atlas, this one is my favourite. So much is going on in terms of history, context, politics, and society, and it’s set against a highly believable futuristic backdrop and told in a modified form of evolved English. (For example, with the politcal prevalence of corporations in this “corpocracy,” many everyday objects are referred to by their once-trademarked names: people drive fords, download information on their sonys, wear nikes on their feet, watch disneys, and so forth.)

This section occurs as a dialogue, the recorded final interview of an imprisoned clone, or “fabricant,” conducted by a government archivist. It takes place in a futuristic Korea now known as Nea So Copros,which is governed by a political party/doctrine known as Unanimity. Though much of the world is “deadlanded,” technology in this world far exceeds our own. The main character, Sonmi~451, is fabricant who is being asked for her version of the truth in this final interview, before she is sent “to the litehouse.” She begins by talking about her life as a server at a fast-food franchise called Papa Song’s. Sonmi would awaken with her cloned sisters, recite the Six Catechisms at Matins, work 19-hour days serving and cleaning up after “pureblood” consumers, end the day with Vespers, consume something called Soap, which contains nutrients as well as amnesiads that deaden curiosity, and go back to sleep. Fabricants have limited IQ and vocabulary, but know that after twelve years of service, they are sent to a place called Xultation, their “debt” fulfilled to the corporation that owns them. At this point, they become consumers just like purebloods: the ultimate afterlife for a server.

Sonmi~451 is asked to recall the infamous Yoona~939, who worked at the same teller as Sonmi and who was “ascending”: gaining higher consciousness, vocabulary, and knowledge, as well as personality. Dinery manager Seer Rhee noticed Yoona’s “deviations from Catechism” and had her checked out, but physically she was performing as genomed. Yet her aberrant behaviour continued; at one point she woke Sonmi before “yellow-up” when everyone else was still asleep in order to show her a secret—first, that Seer Rhee consumed the fabricants’ Soap as a drug and could be found passed out at his desk; second, the inside of the lost-and-found closet. Marvelling at the consumers’ left-behind jewelry, Sonmi was most shocked by a picture book of fairy tales. The fabricants, who had never been outside the dinery, mistook it for what the rest of the world was really like. Yoona criticized Papa Song and the ideology of Unanimity that has enslaved fabricants. Sonmi, too afraid that they are breaking Catechism, was spurned by Yoona. Hatching an escape plan to reach that world on her own, Yoona~939 was gunned down on New Year’s Eve when she tried to make a break for it.

Sonmi did not at the time realize that her own awareness was growing, that she understood Yoona far more than her sisters did, and she didn’t draw the connection between her blossoming consciousness and the fact that she and Yoona had worked side by side. After the “atrocity” of Yoona~939, two of the fabricants who had reached their twelfth year were escorted away to leave for Xultation. The rest of the fabricants were examined for deviancy, but were all performing as genomed. Although Sonmi does have a comet-shaped birthmark between her collar and shoulderblade that does not appear on anyone else of her stemtype, she passed the exam.

At this point, Sonmi finds her thirst for knowledge growing. She eavesdrops on conversations and watches the dinery’s “AdV” screen as much as possible. And she finds herself pondering the doubts about society and Unanimity that Yoona raised. Once more awakening before yellow-up, Sonmi explores the dinery and discofers Seer Rhee dead from a Soap overdose. She is then confronted by an intruder in the closed dinery: a chauffeur called Chang. She is given a choice: stay in the dinery until the DNA sniffers discover her and accuse her of being a Union spy, or come with him.

Dizzied by the world she speeds through in Chang’s ford, Sonmi is worried that she doesn’t know the correct Catechisms to behave properly in her new world. She is dropped off at Taemosan University, where she is given to a postgrad sutdent named Boom-Sook Kim, who has been experimenting on her without her knowledge. Boom-Sook deserts her in his lab for many days with enough Soap to keep her alive. Another fabricant, Wing~027, enters and explains the situation: he is being experimented on for flameproofing of tissue, and she is there for “cerebral upsizing.” he also gives her an abandoned sony full of lessons and tells her she must learn to read.

Lazy and from a rich family, Boom-Sook has purchased his PhD dissertation and is unwittingly the reason for Sonmi’s stable ascension. Totally unaware of her progress or that he and his plagiarized PhD have caused a huge scientific advancement, he mostly ignores her upon his return, which means she has months on her own to study. Her thirst for knowledge can’t be quenched, and she is soon voraciously reading high-level philosophy and political dissertations, hiding her intelligence and her sony from Boom-Sook.

Boom-Sook and his friends decide to use her for drunken target practice one even, aiming for successively smaller pieces of fruit placed on her head. At this point, she is rescued and brought before Dr. Mephi, Boardman of Unanimity, and “architect of the Merican Boat-People Solution,” who has kept track of her library requests and realizes how evolved her mind is. She is enrolled in the university and told to study whatever she wishes, in exchange for subjecting herself to scientific tests. She was the back-up experimental case, while Yoona was the first attempt, and she is the first stable, fully-ascended fabricant. As such she poses political, ethical, and scientific problems of all kinds. Though she has the illusions of freedom, she recognizes that she is still a kind of slave, with no choice but to submit to the tests.

Sonmi~451 attempts to attend lectures in person, but she is openly mocked and insulted by the other students. To them she is sub-human and has no right to be in their classes. She has the rest of her lectures downloaded to her sony. Noticing her restlessness and self-confinement to her quarters, Mephi assigns a student, Hae-Joo Im, to take her out and show her a good time. Hae-Joo and Sonmi go to a galleria, where Hae-Joo explains that each family, according to their social strata (which is defined by the amount of money they have) are legally required to spend a specific amount of money each month, because “hoarding is an anti-corpocratic crime” (p. 227). Sonmi is mistaken as a fashion-forward consumer who has deliberately facescaped herself to look like a fabricant.

The next evening they spend together, Sonmi requests that they return to her dinery. Disguised, she is recognized by none of the other servers, who seem to have no memory of the Sonmi who disappeared one day, and who have no wish or ability to talk about the outside world or a life outside of serving, in spite of her prompting. The consumers in line accuse her of being an Abolitionist and a Unionist. She and Hae-Joo leave the dinery, Sonmi’s eyes opened to the fact that fabricants really are slaves and nothing more.

are watching a disney entitled The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish. The disney is interrupted halfway through when Hae-Joo receives a message: Mephi has been arrested as Union spy, and Unanimity enforcers are coming to arrest Hae-Joo and kill Sonmi~451 on sight. At this point, Hae-Joo tells Sonmi that he is not exactly who he has claimed to be, and the section ends.

Some Thoughts…

Oh, I love this section, and for so many reasons. First, let’s talk about language. This is first story where Mitchell is doing more than just showing what a good ear he has for dialect and time period. He’s not mimicking Melville or writing modern-day British farce. He is actually creating a new form of English here, one based on the historical and political setting of Nea So Copros. Spellings have simplified (losing the “gh” from words such as “litehouse,” the “ex” for words like “xcise” or “xperiment”), and new words are added to the lexicon, or used in new ways: to betray someone is to “judas” them, for example. People get their teeth “emeralded” to be fashionable, old people are “dewdrugged” to remain youthful in appearance; one “curfews” at night or “thruways” to a new destination. Even “orison” is a word that is rarely used in today’s English: an orison is a prayer, and in this dialect is used as both a noun and a verb: this is Sonmi’s orison, which the archivist has orisoned. The meaning has altered, and seems to speak more to Sonmi’s version of the truth, or her story, rather than a prayer.

Concepts have also been altered in the way society sees and uses them, in particular the concept of the “soul.” The fabricants have no soul, but the consumers do. The soul is quantified in the consumers’ soulrings and is used to purchase things. Because dollar amounts alone determine prejudice and social strata, and because corporations and consumers are what the political system is founded upon, this interpretation of what a person is, what a soul is, is fascinating—and totally accepted by everyone in society, while it seems as foreign to us as free will and individualism would seem to a 12th-century serf. Indeed, the slavery of the fabricants is as normal and acceptable to this society as the slavery of black people in Adam Ewing’s time. The corpocracy is even described by the archivist as the natural order: “future ages will still be corpocratic ones. Corpocracy isn’t just another political system that will come and go—corpocracy is the natural order, in harmony with human nature” (p. 234).

The archivist is a young man, one who is putting his career and future on the line for this interview. Unanimity has branded Sonmi~451 a heretic who has no business being archived because she cannot possibly offer anything to future generations. Genomicists, who see Sonmi as “holy grail,” had to pull strings to have “the right to archivism” enforced (p. 189). Through the archivist’s youth and genuine shock at some of her statements, we see how heretical indeed Sonmi~451’s ideas are. What she has to say about slavery and the flaws of corpocracy are shocking to him. We don’t yet know what happens to lead Sonmi to imprisonment and execution, but we sense that it must have to do with her heretical beliefs and her connection to Hae-Joo Im. As she says, “to enslave an individual troubles your consciences, Archivist, but to enslave a clone is no more troubling than owning the latest six-wheeler ford, ethically” (p. 187).

And speaking of souls and heretics, the total melding of church and state fascinates me here. There doesn’t, in fact, seem to be a word for “religion” at all, nor any discussion of a deity, though religious terminology and imagery is rife throughout the narrative. The fabricants are controlled through their Catechisms and their unflagging (and genetically/chemically programmed) faith in Papa Song as a kind of god. The manager of the dinery is referred to as “seer,” which is both a shortening of the word “overseer” and a word with religious or spiritual overtones. And because Sonmi has done something against the government, she is a heretic. There is also a sort of reverse-Marxist thing going on with the government here. Unanimity is also referred to as the Juche, a political ideology but also a Korean word that refers to the “main body” or proletariat, who control the corpocracy and enforce the quota of dollars every member must spend. We seem to have a blend of North and South Korea in Nea So Copros in this totalitarian, consumerist regime.

The indictment of consumerism is strong here, a lens being held up to our current society, a way of saying “See what we could become?”, which is what good science fiction should do. Catechisms as a way of controlling the behaviour of lower classes is telling as well. The world they live in, though it contains elements to struggle against, makes sense to the characters, just as much as ours makes sense to us. Sonmi watches the movie version of Timothy Cavendish’s section and is puzzled by much about our society that we take for granted: that people “sagged and uglified as they aged…Elderly purebloods waited to die in prisons for the senile: no fixed-term life spans, no euthanasium. Dollars circulated as little sheets of paper and the only fabricants were sickly livestock. However, corpocracy was emerging and social strata was demarked, based on dollars and, curiously, the quantity of melanin in one’s skin” (pp. 234–35). I’m not quite sure which “fabricants” she’s referring to, but it’s interesting that she takes for granted that old people can and should use dewdrugs to remain attractive and that at the end of a fixed amount of time, people should be euthanized for the good of society. But, as we’ve seen across all the stories so far, certain themes resonate. Prejudice and societal predacity may no longer be based on skin colour or gender, but it certainly exists based on money, not to mention the enslavement of fabricants.

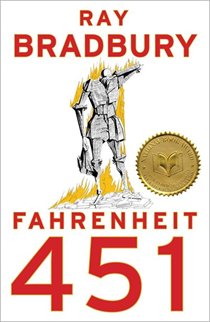

The theme of ascension is at the forefront of this narrative, with Sonmi’s intellectual rise from almost-mindless server to accomplished thinker called her “ascension.” We also see time and history as a sort of upward narrative, with society (theoretically) learning from past mistakes to rise above them, and with Sonmi’s intelligence and understanding ascending the more she reads past thinkers. She also comes across the problem of banned information: indeed, her very name, Sonmi~451, is an allusion to Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. Many of the old treatises and even forms of entertainment, like the “disney” Sonmi and Hae-Joo watch together, are banned by Unanimity, and Sonmi’s own experiences and testimony were nearly banned from being archived. Unanimity is trying to erase any ideas or beliefs that might threaten its existence, which, of course, dooms its society to repeat past mistakes. The slavery seen in Sonmi’s time mirrors that of Adam Ewing’s in the 1850s. Abolitionists are spoken of with the same derision by those in society who benefit most from slavery. Further, without really knowing a lot about the society we’re reading about, it’s tough to tell the difference in ideology between Unanimity and Union. Even he names sound similar, and they are obviously bitter enemies, bent on destroying each other.

Of the several points of connection in this section with the ones that have come before it, my favourite occurs on page 210, the first time Hae-Joo enters Boom-Sook’s lab. Sonmi is still Boom-Sook’s experiment at this point. She has been ignored for months. But when Hae-Joo enters, “he did an unusual thing: he looked at me…Purebloods see us often but look at us rarely. Much later, Hae-Joo admitted he was curious about my response.” This reminds me so much of the first moment of connection between Adam Ewing and Autua: “Then a peculiar thing occurred. The beaten savage raised his slumped head, found my eye & shone me a look of uncanny, amicable, knowing!” (p. 6). Other points of connection include, of course, the comet-shaped birthmark and the viewing Timothy Cavendish’s movie. There are also a nod toward Luisa Rey and her struggles with the evil Alberto Grimaldy, when Sonmi watches a Juche Boardman opening a “newer, safer, nuclear reactor, grinning as if his strata depended on it” (p. 231).

Sonmi also raises some interesting philosophical questions, particularly about happiness. She is lost in existential crisis as she learns more and more yet continues to be subjected to the whims of the university and government who own her: “What was knowledge for, I would ask myself, if I could not use it to better my xistence? How would I fit in on Xultation nine years and nin stars later with my superior knowledge? Could amnesiads erase the knowledge I had acquired? Did I want that to happen? Would I be happier?” (p. 224). Can Sonmi~451 ever fit in with “where she came from” again, or should she, now that she has evolved? She puts it simply and eloquently upon her return to the dinery: “Kelim~889 cleared the table next to us; she had already forgotten me. My IQ may be higher, but she looked more content than I felt” (p. 231).

So what do you think about this foray into the future? Do you like the style of this section? Do you find the social context plausible? Are you rooting for Sonmi~451’s plight?

You might also like:

Does anyone have any references in terms of Vespers, Matins, and molten glass from The Fall that also occur in Anna Smaill’s book The Chimes?

Very pleased to find this webpage as I am close to finishing the book. Firstly, the “sickly livestock” fabricants refer to the Dolly the Sheep clone and subsequent experiments.

I pondered on the meaning of the work “Juche” until I realised it was a very subtle comment on the roots of the ultimate success of corporate interests over mankind’s better side. In Somni’s world the corporate expansion we are now suffering had reached it’s apex, beautifully referred to in the product names becoming the nouns. “Juche” is an evolution of the work “Jewish” to refer back to our time, where most of the world wide brands are owned and managed by people of that persuasion. Jews being traditional traders and ‘shopkeepers’ and their propensity for making money being exaggerated into the results of ultimate greed. In this sense there is an ironic link between the totalitarian world to be achieved at all costs as Hitler wanted to create and the ultimate evils of capitalism ‘in the pursuit of all profit’ that he earlier tried to warn the world against. His ideology and the one he most hated finally end up with the same result in Somni’s future.

Reblogged this on Jottings and commented:

somni’s story – cloud atlas

the ‘fabricants’ in The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish being referred to as ‘sickly livestock,’ is a reference towards the sheep Dolly cloned in 1997, one of many hundreds of attempted clones, but the only healthy or nearest healthy one that they could create. Also cloning has been done of some cattle in the US for beef production, and there may one day be a form of “Savings and Clone” for household pets in the near-future.

I’m not sure if someone has already pointed this out, but Somni’s name means sleep. I wonder if that has anything do to with the fact that Ayrs saw Papa Song’s restaurant in a dream.

Seeing as how I have found this blog nearly a 1/2 year later, I’m sure everyone has moved on from Cloud Atlas. But I’ll comment any how. I have just completed Sonmi’s story and it is by far my favorite.

I wanted to point out another parallel I noticed from Luisa Rey’s story. In the beginning of part 2 of Somni’s story, as they are fleeing Unanimity capture, she says “The ford gathered speed, weight, and weightlessness. The final drop shook free an earlier memory of blackness, inertia, gravity, of being trapped in another ford. Where was it? Who was it?” I believe this is referring to when Rey’s car is pushed off the bridge (“the Beetle lurches out into space”) by Smoke at the end of part 1 of Rey’s story.

Admittedly, I had not heard of this book until the movie came out. I watched it and was confused for much of it but decided I liked it in the end. I was curious the original format so I decided to read the book as well. Somni’s story left me feeling…..deceived. I went into the book knowing (or thinking that I knew) how each story would end. I was really engrossed in Somni’s story and sympathized with her character. Only to discover that she was just a pawn in a drawn out Unanimity scheme. From the movie, I thought Hae-Joo was her friend and lover…but really he was just using her like everyone else in her life.

P.s. I also totally missed the Fahrenheit-451 reference haha

Oh no!!…I’m just now realizing this page is only looking at part 1 of Somni’s orison…it’s a bit of a spoiler. Sorry!!!!….and unfortunately I am unable to delete it

I really enjoyed this section. As a science fiction lover, it definitely appealed to a lot of things I love about the genre. Especially since it reminded me of Blade Runner and other Philip K Dick stories. I totally missed the Farenheit 451 reference, but now that you point it out it’s glaring, so I feel a little sheepish for missing it.

Like you mentioned, it hold a mirror up to our own consumerism and asks us how far we’re willing to push it. I also loved the way it touched on what it means to be human. Is it just intelligence that sets us apart? Should Sonmi be treated differently because she has “ascended” or should all fabricants be extended the same courtesy? Or should we even have fabricants? (Frankly I find the whole idea rather creepy myself).

I really felt for Sonmi in this story, and I enjoyed the format of it’s telling (the interview style). It really helped keep the suspense up, because we only found things out when Sonmi decided to tell the interviewer. I can’t wait to find out what happens to her next. I have to admit though, this isn’t my favourite section (although it’s close). There’s something about Cavendish that still grabs on to me a little bit tighter.

A Blade-Runner-style world is absolutely how I picture it! I love the big questions brought up here. As you say, the nature of intelligence and humanity, and the role or even the existence of fabricants at all, let alone as an underclass of slaves…I find Sonmi wonderfully sympathetic because she seems so guileless and straightforward. She wants to tell her story, her truth, she doesn’t care if it makes the Archivist uncomfortable (in fact, she perhaps *wants* to shake him a bit), and I always felt like she was buffeted along by the choices of others, doing her best to keep her head above water.

My favorite section of the book. Things are getting strange in this world: People chatting without never meeting or seeing their faces (like us in this blog). And there are some things that have become a rule like having a e-mails to participate.

My favourite too–seems it’s a popular choice, in fact! Great points about the anonymity and we can see parallels for that in technology today (particularly given that this book was published eight years ago).

I just like to point out how the word “cuckold” is used pretty much in every one of the stories. I mean I’ve heard/read that word only once in my life before this book and here it is mentioned 4 or five times in this book alone. What’s the deal with that? Anyone else found this odd?

Interesting. I hadn’t noticed this one. Entirely possible that this plays into the idea of the predatory nature of humanity…that one person would prey on another by taking someone they love, or someone who “belongs” to them. I remember the use of the term in this section because Sonmi is very careful to point out that she’s using the word deliberately.

It’s kind of like “slooshing.” I’ve noticed that pop up a few times throughout the narrative, and I’m not sure if it’s a deliberate reference to the sixth story, or if that happens to be a verb that David Mitchell just likes!

I can’t believe it took me this long realize how specifically Mitchell links his comment about “individuals prey upon individuals, groups upon groups, and nations upon nations” to the actual structure of the book’s six narratives. The entire novel is built on the “ascension and descension” themes that you’ve written about, not just in the individual narratives themselves but in the actual order in which they’re shown.

We start out at the “Individual” with Adam Ewing and Robert Frobisher, climb to the “Group” with Luisa and Cavendish, and finally reach the apex of “Nation” with Sonmi and Zach’ry. Then we descend back down, all the way to “Individual” again, where it ends with Mitchell’s view about choice and individuals (which I won’t spoil for first-time readers).

Ooooh. Fantastic observation. I hadn’t put that together either.

I think we could go even further with it, and point out that each of the three categories seems to have an example of “prey” and “predator”. In the “individual” category, Ewing is the “prey”, and Frobisher is a “predator” (or so it seems – Frobisher Part 2 plays chaos with that). In “group”, Seaboard is the “predator”, while the elderly (including Cavendish) are the “prey” in his chapter. And in “nation”, Nea So Copros is a brutal predatory state preying on our protagonist, while in “Sloosha’s Crossing” Zach’ry and his people are being preyed upon by the brutal Kona.

I agree with you. I think this is a deliberate structural choice. It’s like the two sides of the glance between Adam/Autua and Sonmi/Hae-Joo. I think there are likely many of these “both sides of the coin” moments throughout the book, many places where David Mitchell is giving us different sides of the same type of scenario. Even with Henry Goose’s offering of medicine to “help” Adam for his own personal gain and Meronym’s refusal to heal Catkin because she wants to preserve the natural order of the valleys…

Thanks so much for writing these, I’m really enjoying them! I’m currently listening to the audiobook for the first time (which has its own merits- if you can imagine 6 wonderfully different narrators) and I miss out on things like the new way of spelling words in Nea So Corpros.

I didn’t pick up on the 451 reference, or the connection to the eye contact in Ewing’s chapter. I think it’s beautiful that the Cloud Atlas reincarnation got to experience both sides of that encounter.

In terms of how realistic this future is, I think Corpocracy already exists in a way. It feels like corporations have more control over legislation these days than citizens. I think using clones as labor would be way too resource-intensive to ever work (won’t get into this bc it’s explained in pt 2). Machines and artificial intelligence seem to be a much cheaper way of getting things done. It would be interesting to see an additional story that shows the predation of humans on AI that have a sense of self!

Thanks for commenting! I’m glad you’re enjoying the readalong. I’m having a blast writing it–it’s so great to examine a book in such detail (and not because it’s mandatory for some course!).

Oh interesting re: audiobook. That would add a whole extra layer of interpretation to an already complex book. I imagine I’ll be somewhat Cloud Atlas’d–out by the end of this readalong, but I’ll definitely make a note to check out the audiobook at some point. I can imagine Sloosha’s is somewhat difficult to follow in audio format.

I definitely agree that Mitchell is magnifying and codifying something that already exists in today’s society, and I think that ties into Brett’s point below, that there is a sense of modernity within this futuristic society. Interestingly, I had trouble with the concept of corpocracy the first time I read this section because I didn’t immediately make the leap to corporations but rather thought the “corp” had to do with “body.” So I read it at first as a sort of body-related government, a privileging of the pureblood body over the cloned body. Which it sort of is, even though it was a misreading!

Since I haven’t physically read Sloosha’s I can’t say how adapting to the text compares with adapting to the spoken language in that chapter. What I can say is that whoever was in charge of that narration did an amazing job. The voice actor spoke so naturally that you don’t even question the valadity of the strange tongue. The accent was a warped dialect and it worked perfectly with the setting. I’ve seen people give advice for reading that chapter by saying to imagine the accent is Southern (as in the southern states of the US).. And all I can think is “No! It’s Hawaaiin!”. I would recommend trying to just get a small sample of the audio, even from YouTube or something, just to see how they interpreted it.

Oops I meant to say that *the accent is a warped Hawaaiin dialect.

I’m curious about that as well. It reads like something that would be much more understandable when heard, as opposed to read. I’ll see if the library here has the audiobook (I own the e-book for Cloud Atlas).

I thought it sounded somewhat southern in the preview screening of the film I saw, but then, Zachry is played by Tom Hanks and not a young and then teenaged boy, so, you know. Differences. I’m not sure I know what a Hawaiian accent sounds like. I am deeply curious now. Unfortunately the library doesn’t have it. I’ll track it down somewhere!

What I find (and what I’ll talk about on Tuesday) is that the more I read Sloosha’s, the easier I find it. You sort of slip into the rhythm and your brain recognizes patterns. The first bit is hard but you settle right into it.

Slooshas crossing audio book part was the absolute best! I started saying “nay” and “spec” ( spesh as in special) when talking , lol! Ps I’m Jennean and just finished the reading the e-book and listening to the audiobook together. I’d read at home and then listen to what I’d read in the car or whatever, on my iPod. Best book ever. I also liked iBook format because I could touch a word I didn’t know and instantly get its definition.

Thanks for reading and commenting, Jennean! I imagine reading and listening to the book at the same time makes for an incredibly immersive experience!

Funny thing is, I listened to the audiobook as well, and my thought with Sloosha’s was, “I’m glad I got the audiobook, because I can’t imagine reading this.” 🙂 The narrator makes it extremely natural sounding, and is amazing. That was probably one of my favorite parts of the book because it was just fun to listen to, and want to play snippets for my wife to give her a feel for how it sounds.

I’ve got to get my hands on a copy of this…and you know, as much as my first reaction was that it must be terribly difficult to follow Zachry in audiobook, I also found myself quoting it to my partner because I wanted him to hear how the language sounded, how it had evolved.

First, let me say that I am really enjoying this read-along. I am reading Cloud Atlas for the first time, despite having bought the book years ago. I was motivated with the movie announcement to get it read sooner.

Just wanted to add a small bit to your analysis. When Sonmi referred to the “only fabricants were sickly livestock”, I think she is referring to genetically modified livestock, for example, the EnviroPig, a pig modified to process phosphorus more efficiently that natural born pigs.

Thanks! Glad you’re enjoying it! I’m so glad people are responding–it adds so much more to my understanding to here what other people think and react to as well.

And aaaah, that makes sense. I thought Sonmi was specifically referring to what she saw in the Cavendish film, and wondered if she thought the nursing staff or some other members of society were fabricants, hence my confusion. But for Sonmi, a fully sentient human clone, to learn about Dolly and her ilk would probably be as shocking sa someone first understanding that we evolved from monkeys….

You know… after I made my comment I reflected on what you wrote in your analysis, and doubted that TC would have mentioned GM animals. Sonmi must have learned about them from researching her sony, though I don’t remember any specific mentions in the book.

She’s referring to animals like Dolly, the first cloned sheep (1996).

I really enjoyed this chapter, too. The homage to Blade Runner and Brave New World seemed obvious from the get-go, particularly with the term “Fabricant” (reminiscent of the “Replicants” of Blade Runner). The pacing was good, and so much of it is about Sonmi discovering more of her world as she awakens, with a fresh perspective on things that others consider ordinary. It’s probably my second favorite chapter in the whole book, after Part 2 of the Sonmi section.

I’m not sure I entirely buy the plausibility of a future slave class of humanoids, or the Enrichment Statutes. There seem to be few robots for such an advanced society, and consumption is not necessarily the ultimate goal of corporations (I’m guessing that the banks and financial institutions were major losers when this society formed in the story).

I still find it quite fascinating, as the apex of the Predatory Society. Every level of its pyramid is built around extracting from below, with the Fabricants at the bottom.

Sorry, I had to type my last two paragraphs in my post in a hurry. To expand –

In fitting with Mitchell’s theme about humanity’s nature as the “Cloud Atlas”, I feel like there is a sense of “modernity” in Nea So Copros, even amidst their advanced technologies and occasionally alien customs (such as mandatory euthanasia). This is not surprising, since much science fiction is about holding up a mirror to some part of contemporary society so that it might be examined through symbolism, allegory, or parody.

I don’t find it completely plausible, though. Even assuming that their identity as being genetically unchanged is paramount (hence the “pureblood” moniker), nobody in either Nea So Copros nor the “sickly democracies and democidal autocracies” that exist elsewhere has sought to turn their incredibly capable genetic engineering capabilities on themselves and their children? Even when it literally means the difference between survival and extinction in the encroaching deadlands?

All that said, I personally find it fascinating. While it may not be entirely plausible, it is still incredibly compelling as a depiction of an entire nation that is fundamentally predatory. Every aspect of it, even the consumerism that blankets it, is just the surface trapping of a society where someone is constantly being fed upon by someone above them, all the way to the Xecs who make up the society’s aristocracy.

Oh, definitely see the influence of Blade Runner and Philip K. Dick in general in this narrative.

I love the layers upon layers of predacity in this story. Even the people who are helping Sonmi are doing so for predatory reasons. Sonmi herself seems to be the only person not preying on anyone else in this section.

I also enjoy the suggestions of history that we as readers don’t know about, the casual mentions of “deadlanded” countries, and the mention of the safer nuclear reactor…is it nuclear disaster that has ruined so much of the globe? And could Nea So Copros even exist without the exploited underclass of fabricant slave doing the menial and dangerous jobs?

A nuclear aspect of the deadlands would definitely fit with the recurring nuclear element that appears in a couple of the chapters, and also fit with the “Skirmishes” as a series of conflicts that up-ended the international order while sparing the Korean peninsula from devastation. I figure it’s a combination of that, pollution, ecological collapse, and areas that are dangerous because of diseases still lingering in the soil and water.

I just realized that the particular kind of consumption that is available to the lower and middle pureblood strata is a more subtle way that the Nea So Copros oligarchy feeds on them, along with the forced wealth and income transfer that is the product of the Enrichment Statutes.

I don’t think it would survive without the Fabricants. The fabricants’ labor is the only thing that allows for the combination of high productivity and lots of leisure time underpinning the regime’s primary method of pacifying the populace (lots of consumer goods).

The nuclear angle probably also explains the red scabbing illness that we’ll see in the next section, and the birth defects in the babies born in that era, too.

Excellent point about the particular kinds of consumption available to the lower strata. Levels of control nestled within levels of control…

Correction: The Prescients did modify their children to be more melanoma resistant by darkening their skin.