|

|

|

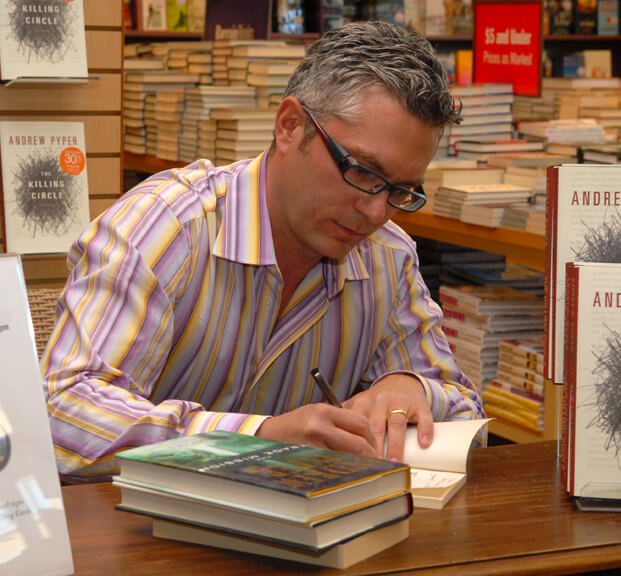

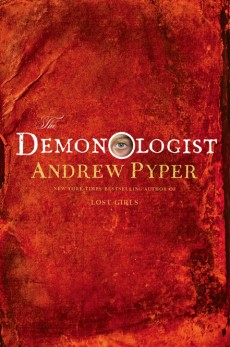

In Andrew Pyper’s The Demonologist, (available March 5th) Professor David Ullman discovers that demons exist—and that they are the reason his beloved young daughter has been taken from him. I recently talked with Andrew about the bread crumbs his protagonist must chase, and the world of emotional horror that opens before him. . .

What brought about the genre shift to horror?

In hindsight—because all of this is hindsight when I talk about the “category” of the book, it’s all post-facto analysis—I was just following my nose in a narrative way and going where the story took me. But I think, why did it take me there? Because I’ve always been interested in the supernatural. It appears glimpsingly through almost all the previous novels, but in a kind of partial way. And this story demanded, because it entertains the possibility of demons existing alongside us in the real world, the creation of an entire world. Whereas the previous novels required people putting up a forbidden window, this is like, no, no, you have to build an entire premise whereby all human action will be infused with the supernatural companionship with demons. So once I recognized that, it felt quite liberating. I didn’t feel like there was a constraint of rules—although you can’t go that far, because that would make it a different kind of book. There was no sense of rules that might be broken.

It’s interesting to me, the idea of demons living alongside us. You play with this Miltonic idea of Hell not being a physical place, but living in us and alongside us. Unlike, say, in a movie like Constantine, where Keanu is transported to Hell, in The Demonologist we have these hellish things happening in our minds and all around us. Is that a conscious choice to stick with this Miltonic idea? What brought about this vision of Hell for you?

It is in part born because Milton is obviously an influence on the novel, a text that I used both thematically and to a degree mechanically, but I think that commitment, that is, the commitment to realism, having the story take place in the real world with these impossible supernatural beings moving through it, that was just an aesthetic choice of my own. I love horror and I love fantasy, but when it comes to those kind of stories, I’m definitely on the muted, restrained “keep it real” end of the spectrum. I know some people are like, “No, if you’re going to talk about Pandemonium, why don’t you take us inside Pandemonium? Let’s see the floor plan.” Mine’s a more internal, psychological Pandemonium. That’s just what I prefer. I personally like those kind of stories, like Rosemary’s Baby, where this is a story about the Satanic but it actually takes place in present-day New York.

© Christ’s College Old Library