Part 1: Introduction & Warnings

The Story So Far…

We begin with an explanation of what we are about read, in the clipped tones of a professional. . . or a survivor, whom I’ll refer to as the interviewer. There is no indication if this is a man or a woman, how old, or what country this interviewer is from. The world, the interviewer tells us, has been an at peace for a decade, and the interviewer has compiled information for the United Nations Postwar Report committee chronicling what has been called “The Crisis,” “The Dark Years,” “The Walking Plague,” and “World War Z.” S/he (forgive the clunky hybridized pronoun) included many human testimonials that s/he was asked to remove by the committee chairman, who only hard facts in the final report. But the interviewer believes there is great value in preserving the human element of the wartime memories—preserving, lest the stories be lost and we repeat our own mistakes. And so, the interviewer has turned these oral testimonials, which s/he has tracked down from survivors all over the world, and turned them into a book, a history of World War Z.

The first section, “Warnings,” takes us all over the globe. We begin in Greater Chongqing, China, where the interviewer talks to Kwang Jingshu, a doctor. Kwang recalls meeting Patient Zero. He was called to the village of New Dachang, whose residents had been relocated when the government needed to build a dam where their homes stood. Outside the meeting hall where the sick have been placed, he finds villagers too terrified to go inside. He is told it isn’t safe, but he dismisses their fears of sick people as peasant superstition. Inside, he finds six patients, running fevers, not coherent, and all with a bite mark somewhere on their bodies. He is surprised to see the bite marks appear human, and are very clean, showing no hint of the bacterial infection that should be common with such wounds.

Then he asks to see the seventh patient, the one who started outbreak. This Patient Zero is a child who became sick after a bout of “moon fishing”—diving into the wreckage of the old town, now deep underwater in the new dam, for salvage or looting. Before losing coherence, he claimed to have been bitten by something down there, and his father, with whom he was diving, was never heard from again. But the person the doctor encounters is unlike anyone he’s ever met before: he is cold, his skin grey, and he’s rubbed against the restraints he’s been put on so much he’s scraped all the skin away. And yet there is no blood. Kwang orders two large villagers to hold the boy down as he tries to examine him, and the boy struggles so violently he breaks his own arm under the weight of one of the peasants. He shows no sign of pain, or even knowledge that his arm is broken. He twists away and tears the limb completely off, freeing himself from the bonds holding him. And he goes after the doctor, who quickly runs and locks the boy into the room.

Grim now, Kwang calls an old army buddy, Dr. Gu Wen Kuei, and shows him via videochat on his cell phone the other six infected. Gu, who was initially cheerful and friendly, becomes all business, instructing him to restrain in the infected and vacate and secure the room if any of them fall into a coma. “Support,” Gu says, is coming. And then, most ominous of all, Gu tells Kwang something in a kind of code. When they were in the army, in a skirmish against the Soviets it seemed they would not live through, Gu said “Don’t worry, everything’s going to be all right.” He repeats this phrase now, and Kwang knows they’ re in deep trouble.

As the “support”—the army—arrives, an old woman tells them that this is punishment for the government’s choice to flood Fengdu, the City of Ghosts with temples and shrines devoted to the underworld. Kwang, the interviewer tells us in an addendum, was arrested and held without charges until well after the outbreak had spread outside China.

in Lhasa, Tibet, which the interviewer tells us in now the world’s most populist city, we meet Nury Televaldi, who worked as a “shetou,” a person who smuggles people across borders. When people were just starting to get sick, he worked in Thailand and Myanmar, helping the ill try to get to western countries where they thought they’d get better medical attention—for a serious profit, of course. People were smuggled by land, as well as by sea and plane—until, he says ominously “Flight 575.” On that particular flight, he heard tell that a businessman who had a small bite was trying to get to Paris with his wife. He made it to the Parisian hotel before the sickness overtook him. Televaldi thinks this may be where the Parisian outbreak started.

Others he smuggled disappeared into “the host country’s underbelly” upon arrival, or as the interviewer restates “the low-income areas.” This, says Televaldi, explains why the outbreaks started in “so many First World ghettos.” Poorer countries who bordered richer ones, such as Mexico, actively allowed the sick in for a fee, knowing they would then head into the richer countries. Those who became sick, or whose symptoms became apparent, on ships were often tossed directly into the ocean, only to wash up on islands, still writhing. He tells one story of a driver he saw transporting an obviously infected group to Kyrgyzstan.

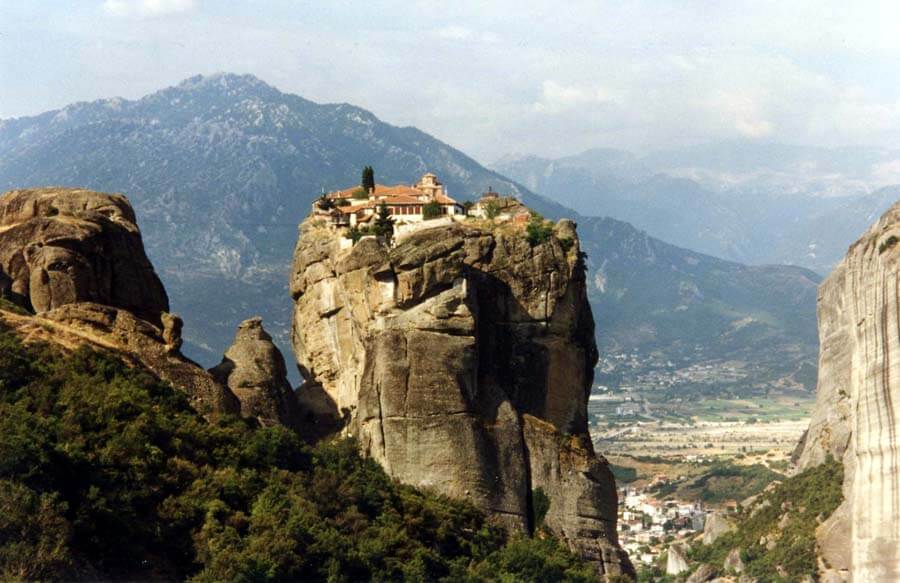

In Meteora, Greece, the interviewer meets with a Canadian, Stanley MacDonald, of the Princess Patricia Light Infantry, currently living in a monastery built atop almost vertical columns. He was in Kyrgyzstan involved in “drug interdiction operations” when the outbreaks began. He speaks of finding caves in “that rocky wasteland,” (loc 311) and inside after following a bloody trail, bodies. Some had been trying to escape from something and ended up dying in their own booby traps. Some had been torn apart. The only “intact” bodies, not missing limbs or other pieces, had died of head shot wounds, all with “meat, chewed, pulped flesh bulging from their throats and stomachs.” In the last tunnel they checked, they found a hand still moving from underneath a pile of rubble. Digging in, they found that “first the arm came free, then the head, the torn face, wide eyes and grey lips, then the other hand…the waist down was still jammed under the rocks, still connected to the upper torso by a line of entrails” (loc 354). He was told upon returning to Edmonton that this was a result of “unknown chemical agents” and incarcerate him for “evaluation.”

In the Amazon Rainforest, Brazil, the interviewer meets with Fernando Oliveira, once a doctor, now a drug addict who lives with, or is held captive by, the Yanomami people, whose village hangs suspended from trees and whose population came away relatively unscathed. In Rio, Oliveira was to perform a heart transplant, illegally, for a patient named Herr Muller, who suffered from a condition called dextrocardia where his heart was formed and situation backwards (the left aorta on the right side of the heart, and so on). The donor heart had to match this extremely rare situation, and it likely came from China, through a broker in Macau. After the operation, the doctor Oliveira was working under, Dr. Silva , dismisses the younger Oliveira’s concerns that the comatose patient seems ill, instructing him to go blow off steam.

After many hours, Oliveira receives a frantic phone call from his receptionist. Upon returning to the clinic, he finds the receptionist and the nurse beside themselves with fear. He takes his gun and goes inside, to discover blood seeping from under Herr Muller’s door. He enters the room to find Muller hovering over Silva’s body, bits of meat in his mouth, black liquid oozing from his gaping chest wound. Horrified, Oliveria shoots him in the head. The police, Oliveira says, were his partners in organ procurement, and helped him clear up and hush up the mess.

Muller’s wife was lucky, Oliveira muses. Though the infected heart of the donor would have sent the infection to the brain in seconds, if other parts were used in other transplants, for example kidneys or a skin graft, the patient may well have gotten home before succumbing. Oliveira has no idea if the person who harvested the organs knew they were infected, but he points out that the “Chinese army. . . they’d been making millions on organs from executed political prisoners” (loc 459). Who knows, he muses, how many infected organs could have been transported out of China before anyone know what they were dealing with. He hypothesizes that this is how much of of the outbreaks began.

In Bridgetown Harbor, Barbados, the captain of the “Infinity Ship” Imfingo, one Jacob Nyathi, remembers growing up in South Africa just after Apartheid. He recalls his father pushing the family to abandon old tribal ways and modernize, move to the city. On his way home from work one day, he hears gunshots. Not uncommon in his neighbourhood of Khayelitsha, he takes cover, but the gunshots only intensify. He sees a mob, fleeing, and fights his way through them to find his family, on the way seeing a group of infected people in shanties, moaning and slouching toward him. He attacks the closest with a cooking pot, hitting the infected over and over, not slowing the attack at all until at last he breaks the skull and damages the brain. As he flees, trying to convince others to run too, he is taken down by a bullet to the shoulder. He awakens some time later in a hospital where he hears of outbreaks of “rabies.”

In Tel Aviv, Israel, the Israeli intelligence operative Jurgen Warmbrunn recalls to the interviewer “Most people don’t believe something can happen until it already has. That’s not stupidity or weakness, that’s just human nature” (loc. 567). His agency first received warnings about the outbreaks from Taiwan but assumed the code must be wrong: surely the message about dead bodies reanimating back to life and eating the living couldn’t be the correct message. But at his daughter’s wedding, he speaks with a professor who tells him about the “rabies” outbreak in Khayelitsha, how golems were on the rise there. But these were not peaceful golems. These were bloodthirsty.

Stephen T. Asma © 2008

Warmbrunn begins combing through UN documents, finding mentions of the accounts from Rio, Kyrgyzstan, and China, and coming to the understanding that these outbreaks are real and that the only way to stop the reanimated sick people is by destroying the brain. “Isn’t it the only way to annihilate us all?” he muses (loc 617). His findings, combined with those of American government agent Paul Knight and fifteen others, became what is now known as the “Warmbrunn-Knight” report, and he laments that if more people had heeded it, they wouldn’t have needed the battle plan put together by South Africa.

And finally, in Bethlehem, Palestine, the interviewer speaks with Saladin Kader, a Muslim professor who was a teenager in Kuwait City when the outbreaks began. The younger Kader thinks Israel’s invitation to all Israelis, Jews, and even Palestinians to take shelter from the outbreaks in Israel, a “voluntary quarantine,” is “a Zionist lie,” but his father forces the family to go after the second major outbreak in their area. Kader rages against his father, but they do go, and at the border dogs sniff out the infected, who are turned away no matter their background or political affiliation. Once in Israel, they are placed in a “resettlement camp,” a crowded, guarded tent city. They are also subjected to numerous medical tests. When they are cleared three weeks later with clean bills of health, they’re allowed to leave the camp.

But peace doesn’t last: the Israeli Civil War commences with an armed uprising of Jewish rebels in Beer Sheeba. So much is going on politically that the young Kader doesn’t understand. To his horror, amidst the violence he sees a van blown up and “figures climbing out of the wreckage, slow-moving torches whose clothes and skin were covered in burning petrol” (loc 768). He suddenly understands what Israel has been trying to warn the world about.

Some thoughts…

Right away, it’s clear this isn’t your usual reading experience. There’s no central character apart from the totally unknowable interviewer. Each of the seven narratives calls to each other in some way, builds on each other to begin to show us a picture of what is going on. But this book was written ten years after VC (Victory in China) Day and the end of the Zombie War. These people are referring to events in their collective past that need no real explanation. When Televaldi mentions “Flight 575,” anyone still alive in this world would immediately know the meaning of that, its history, the part it played in the outbreaks. We, the readers now, aren’t given too much explanation. It’s a great plot device, allowing us to sink into this world and become totally immersed in its strangely believable premise. What feeds into this are colloquialisms: the outbreak is called The Crisis, The Dark Years, the Walking Plague, African rabies. Or, as the interviewer says, the newer and more “hip” terms for what happened: World War Z or Z War One. The interviewer hastens to tell us that s/he doesn’t like the latter term because it implies that an inevitable Z War Two must come. I love this vague distaste we sense the interviewer has for these terms, conveyed by the quotation marks around “hip.”

Patterns begin to emerge in the “Warnings” stories. Disbelief about what could possibly be happening, misunderstandings and rationalizations: it’s rabies, it’s demons, it’s golems. It’s a treatable disease. One old woman in New Dachang claims this is the punishment for drowning Fengdu and its temples devoted to the underworld. We also see the outbreak spreading through a combination of selfishness and selflessness: those who will do anything to save themselves and those who will do anything to save those they love, no matter the cost to others. And, of course, those at both an individual and a government level who don’t mind making a profit from all of the suffering. Realization that those with bite marks must be contained, and that those who have succumbed can only be taken down by destroying their brains. Not to mention that when it’s all over, the places where populations have managed to survive, if not thrive, are in remote locations; the tree village of the Yanomami, the monastery buildings in Greece.

Too, we get a glimpse of just how much havoc has been wreaked. In Chongqing, the interviewer tells us, where 35 million people once lived, there now only 50,000. That’s less than 1% remaining of the original population.

Brooks never overplays his hand here. The Z-word has already been dropped. We know the kind of book we’re getting into. And yet we’re learning about exactly what happened through eye witness accounts—accounts, we have to remember, of events that took place over a dozen years ago. These are unreliable narrators who are telling us what happened through the lens of their later experiences. This allows us to experience some serious dread. As Kwang first approaches the village, he tsk-tsks away the villagers’ fears as peasant superstition, the kind of thing that needs to stamped out in the face of reason. And yet the moment he sees Patient Zero, sees where the skin has rubbed away but hasn’t bled at all, we know bad things are happening. And the moment that arm breaks and then tears away, we feel the same terror poor Kwang must have felt. More terrifying still: Gu is grim but in no way shocked by the infected. There’s a military protocol that’s clearly in place. Somewhere in the government, they knew this was coming.

We see a lot of the world’s political situation as it was before The Crisis. So much emphasis is placed on internal conflict in the latter half of the twentieth century, into the twenty-first century (when, I presume, the outbreaks occurred. People are still alive who fought in 1969 wars, or who were born as Apartheid ended, so the outbreaks must have occurred right around the time we’re living now). References to border skirmishes between China and the Soviet Union, gun violence in South Africa and Brazil, Chinese illegal export of organs harvested from executed prisoners, the war on drugs in Kyrgyzstan.

A few things I’m left to wonder: is it significant that there are references across these different testimonials to one another, for example when Warmbrunn refers to the story of a Brazilian nurse who talks about the murder of a heart surgeon? Second, is there significance to the fact that Jacob Nyathi is the private owner of a futuristic boat the type of which is normally owned by governments and not people? Third, just how much was known before the outbreaks became widespread? What did the Chinese government know? Were other governments preparing themselves as well? Will we find out the original cause of this disease?

Please feel free to leave comments on what you thought of this first section of the book!

You might also like:

|

Turning 30: the 30 books that have shaped the reader and person I am |

I really enjoy seeing the pictures that you’ve posted; they do bring another level of appreciation to the episodic elements of the story. We share a lot of the same questions, but I find myself just reading on, turning the pages, not really trying to suss anything out about the story, not overly aware of the unanswered questions. I don’t have the sense that, if I just pay more careful attention, I will have a greater understanding of the events; I feel very much an outsider. And, given the nature of this story, I’m quite alright with that status! I will read on…

I was slow to like this book. There was something about the interview format that I didn’t care for. But, as the story is progressing, I’m appreciating it more and more. I particularly enjoy the differentiation of this story versus conventional zombie stories. This story is laying a foundation for a much slower outbreak, or at least, a seemingly more detailed discussion of the spread of the “disease.” I followed your Cloud Atlas Readalong long after it was written. I’m very pleased to follow this one, coincidentally, as I’m reading it myself. Thanks again for your fantastic dissection of selected titles, unlike any I’ve read before. Cheers from SoCal.

Thanks for coming back for this readalong, C.J.! This is not generally my genre, but I’m fascinated by the way Brooks is building up the world for us so far, showing us the origins of the disease and the possible vectors for its spread.