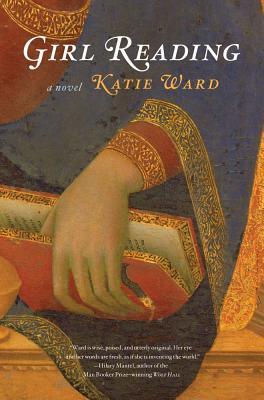

Seven women in seven different eras contemplate reading and art in Katie Ward’s ambitious debut novel Girl Reading. Each section introduces a new story, a new set of characters and circumstances, and a new work of art that was inspired by and includes the likeness of a girl or woman reading.

“I look through your notes again and they seem so delicate, dropped leaves. I like the unfinished poems best because it feels as though you have been interrupted momentarily, called away to make a decision about the horses or the baking, will be back shortly to shine them up.”

– Girl Reading, Katie Ward

Seven women in seven different eras contemplate reading and art in Katie Ward’s ambitious debut novel Girl Reading. Each section introduces a new story, a new set of characters and circumstances, and a new work of art that was inspired by and includes the likeness of a girl or woman reading. In doing so, Ward gets to create rich stories in different time periods while discussing the nature of art and the role of reading in women’s lives.

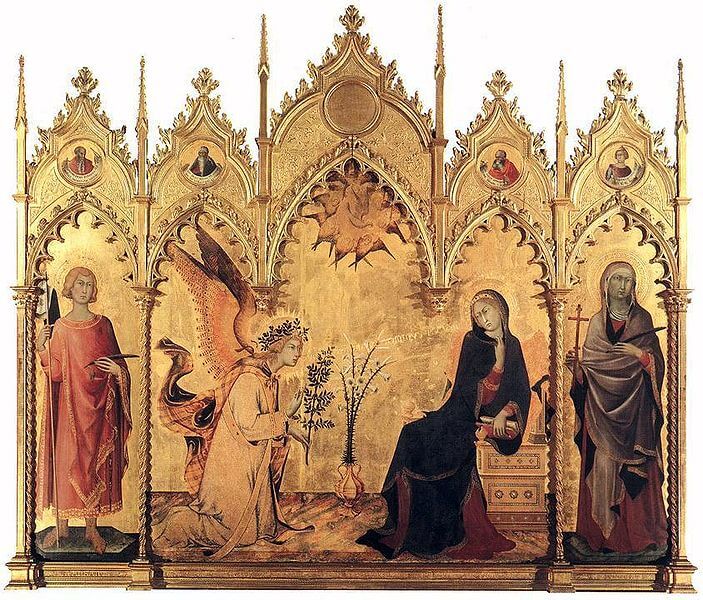

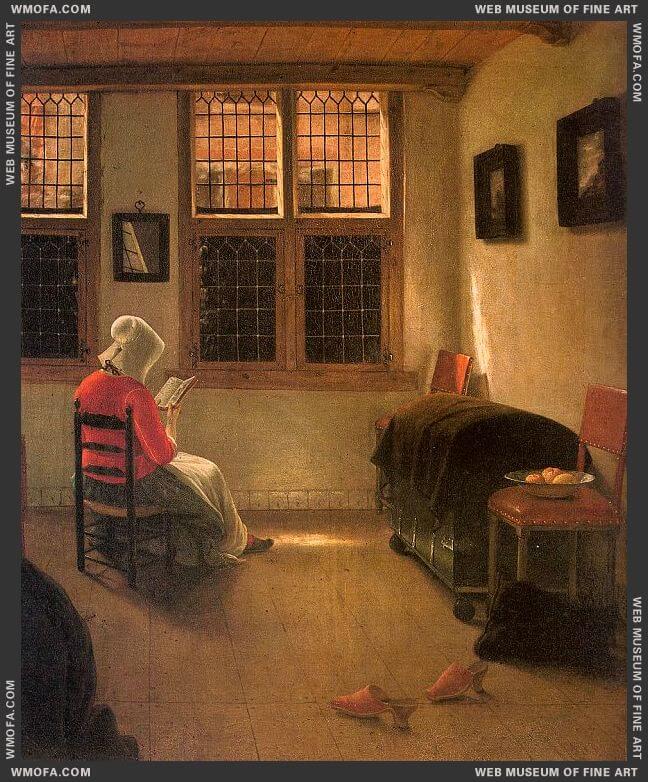

While called a novel, this is, in fact, much closer to a set of seven themed short stories or very short novellas. They range in place, time, and context, while maintaining a similarity of tone throughout. First is Italian master Simone Maritni using an orphaned girl as his model of Mary in his Annunciation in 1333; next a deaf woman named Esther works as a maid in the household of Dutch artist Pieter Janssens Elinga in 1668; third, a celebrated female portraitist paints a likeness of a dead poetess for her grieving lover, a Lady in British society who has fallen into despair in 1775. Next, we come to a set of twins who have chosen very different lives, one as a famous spiritual medium and one as the wife of a photographer in London in 1864; then, a girl in 1916 on the cusp of womanhood falls in love with an older artist, and finds herself embroiled in all of the adult issues and entanglements around her; and sixth is a determined young woman, who works for a British MP, has high career aspirations and a terrible boyfriend. Her picture is taken and posted on Flickr in 2008.

Each of these stories stands pretty well alone, and could be read as a short story and a meditation on art or gender roles or history. They touch upon similar themes, in particular the difficult roles women have had to play, the way they have so often been preyed upon throughout history, and the reserves of inner strength individual women can and must tap into. Most of the main characters find themselves in untenable situations that they simply must deal with and live through, from being an orphan at the whim of powerful men in Renaissance Italy to a grieving noblewoman shunned by society for being gay, to an empowered present-day woman still at the mercy of her boss and her loutish boyfriend.

The stories are ever so slightly unified by the seventh story. Set in 2060, people spend most of their times in an augmented reality called “mesh” and are no longer able to access real, physical art. An engineer named Sincerity Yabuki is showing off her invention, Sibil, a mesh simulation that shows users the stories behind works of art—in particular, six works of art that each feature a female reading. But Sincerity has a secret when it comes to Sibil, and her story calls up questions about the nature of art, of reality, and of living in an increasingly cyber-connected world.

Ward does a number of things well. Her writing style is confident and nuanced, and it’s hard to believe this project is her first book. She easily brings us to the end of one story, erases the etch-a-sketch, and deftly delivers us into a whole new world of characters and contexts. The settings are meticulously researched and constructed. Her worlds quickly engross you. Her leading ladies are accessible and sympathetic, and are never clichéd. Several stories in particular stood out for me: I was brokenhearted for Esther in “Pieter Janssens Elinga” and for Lady Maria in “Angelica Kaufmann.” The unfairness of their situations and the total lack of control they have to do anything but put one foot in front of the other—Esther far better than Maria—are beautifully written. Likewise, I was entranced by the twin sisters of “Featherstone Of Picadilly,” of their arguments about what makes a fulfilling life for a woman, and for the ultimate dilemma the two share.

I found my interest waning in the more contemporary tales, in particular Gwen’s story in “Unknown” and Jeannine’s story in “Immaterialism.” Jeannine was terribly frustrating: while I didn’t want to read about a super woman, necessarily, the story’s focus on clothing, boys, bars, babies, and working at the beck and call of powerful men in order to further her own career felt disappointing. Surely there is more to say about the modern female experience than these things? Surely we’ve come further than poor Laura Agnelli in 1333, all but given to Martini by the priest and with no say in the matter?

I was also disappointed by the heavily eurocentric bias of the overall book. With the opportunity to look at women’s roles, the nature of art, and the importance of stories and literacy, setting the first six stories in Europe, and mostly, in fact, in England, seems like such a waste to me, and feeds into the usual Western ideas of “great art” and “master artists” being only from Europe. Sure, Serenity Yabuki is of some sort of Asian background, but the world depicted in 2060 has become globalized and the focus isn’t about a particular history but about gathering together the other six stories. I would have loved to see stories from Japan or China or India, from the Tuareg or the Assinboine or the Aztec. Art doesn’t just happen in Europe.

And perhaps this is a small pet peeve, but throughout there are no quotation marks. None. I absolutely despise this convention if it occurs for no good reason. Lack of quotation marks if the entire narrative is being told campfire- or confessional-style by a character is fine. (Junot Diaz is a good example of someone who uses lack-of-quotation-marks well.) Here, there doesn’t seem to be any reason whatsoever for it, and they’re sorely missed. Dialogue is often confusing because it’s impossible to tell who is speaking, or when speech stops and narrative picks back up again. This was a really poor style choice, and unfortunately smacks of pretension.

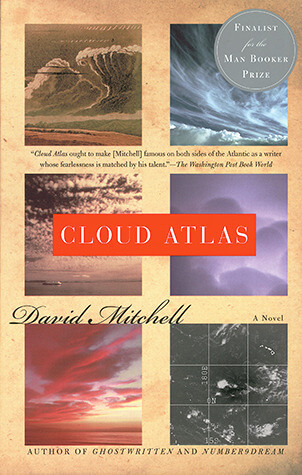

This is a funny book for me to have read this month. I picked it up quite by accident, having stumbled across the title and immediately falling in love with the premise. I’m currently eyeball-deep in an in-depth readalong of David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas , a series of six deeply disparate and yet subtly, intricately interwoven stories. Ward’s writing seems influenced by Mitchell’s style (he does similar things in his also brilliant Ghostwritten), but the lack of connection beyond a sort of overall theme of “reading” and “art” and “women” keeps this book from being truly great. It’s ambitious, but it’s not really a grand, sweeping novel. It’s a set of well-written short stories, not the epic that I imagine it was meant to be.

But give Katie Ward time. In spite of my criticisms, this is an impressive debut novel, with great settings and characters, and big ideas at play. I look forward to reading her second book, whenever that may be.

Three out of five blue pencils

Girl Reading by Katie Ward, published in Canada by Scribner, © 2011

Available at Amazon, Indigo, and fine independent bookstores everywhere.

You might also like:

What a neat concept for a novel. I’d almost want to pick it up just to enjoy the art, though it’s disappointing to hear it’s eurocentric. I’ve definitely seen enough Western European already and would love an opportunity to learn more about art from other cultures.

It would have been an interesting way to draw comparisons and parallels between the lives of women in, say, Tang dynasty China to Falklands-era Argentina to Aborigine Autralia, along with Europe.

It definitely is a neat concept. I’d almost want the author to come back and write it again ten years from now, with more experience under her belt.