Introduction

Part 1: The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing (first half)

Part 2: Letters from Zedelghem (first half)

Part 3: Half-Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery (first half)

Part 4: The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish (first half)

Part 5: An Orison of Sonmi~451 (first half)

Part 6: Sloosha’s Crossin’ an’ Ev’rythin’ After (whole story)

Part 7: An Orison of Sonmi~451 (second half)

Part 8: The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish (second half)

Part 9: Half-Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery (second half)

The Story So Far . . .

We last saw Luisa Rey as her car plunged into the icy waters around Swannekke Island, forced off the bridge by the nefarious assassin Bill Smoke, who works for Seaboard CEO Alberto Grimaldi. As she fights her way clear of her seatbelt and struggles to open her window to escape the car, she sees that the Sixsmith Report is ruined, hundreds of pages swirling through the dark water, and she fears she has “paid for the Sixsmith Report with her life” (p. 392).

The scene changes. Isaac Sachs is on a plane with Alberto Grimaldi. He is musing about the nature of time and memory: is the actual event that happens in the past superseded by the collective memory of what we think happened? As people who were on the Titantic die, are we left with a different version of the Titantic‘s sinking, a “virtual past” that is malleable and based upon the whims and beliefs and hearsay of the present? Does the flipside exist, a malleable “virtual future” based upon our daydreams and beliefs of what the future will hold? He proposes:

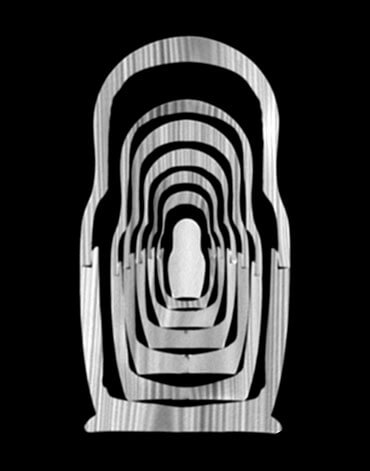

“One model of time: an infinite matryoshka doll of painted moments, each ‘shell’ (the present) encased inside a nest of ‘shells’ (previous presents) I call the actual past but which we perceive as the virtual past. The doll of ‘now’ likewise encases a nest of presents yet to be, which I call the actual future but which we perceive as the virtual future.” p. 393

Finally, he concludes, he has fallen in love with Luisa Rey. And then his plane explodes. Bill Smoke has switched allegiances and has taken out Sachs and Grimaldi for Presidential Energy Guru Lloyd Hooks.

Luisa, meanwhile, has survived and been taken in by nuclear protester Hester Van Zandt. Hester fixes her up, lends her some clothes, and sends trusted friend Milton to get a truck to take Luisa to safety. Milton immediately rats Luisa out to Joe Napier, giving him the details of Luisa’s whereabouts and plans in exchange for cash, and telling him that Napier is the only person getting this information—though we get the feeling the “trustworthy” Milton might be making a few more calls on the subject, too.

Luisa arrives home and discovers Javier hanging out with her “Uncle Joe”: Napier is in her home, but does his best to dispel her fears, telling her his secret. It turns out that he was a cop with her father, Lester Rey. Lester saved his life during the botched operation at Silvaplana Wharf (the one Luisa told Sixsmith about in the first half of this story). He’s repaying the favour by warning her away from her Swannekke digging. He tells her that Smoke killed Sixsmith and is coming for her. Luisa takes Napier’s advice and says goodbye to young Javi, who takes a moment to philosophize about the nature of time, too: If you can see into the future, does that mean the future is fixed? Luisa says that while the far future might be fixed by the actions of others, what happens in the next minute is made up by what you decide to do. Can you change the future? Luisa can’t say.

Art by Yuriy Shevchuk

She goes to her mother Judith’s house, just in time for a big fundraiser. Luisa comes from a wealthy, socialite background, and her mom wants to set her up with one of the dreamy triplets she’d previously mentioned on the phone. Luisa dresses up and trades barbs with old society “friends” who are shocked she’s not married yet. Bill Soke arrives and sweet-talks Judith. Clearly Milton called him, too. As Luisa has never met him in person, she doesn’t know the man her mother is trying to set her up with is in fact Sixsmith’s killer, out to tie up loose ends with her. Luisa does her best to ignore him, fixing her gaze at the TV instead. She is horrified when the news reports the crash of Grimaldi and Sachs’ plane.

Back to work Monday morning, and the news of the day is that Spyglass has been bought out by a big conglomerate. More or less out of hiding, Luisa goes to pick up the copy of Robert Frobisher‘s Cloud Atlas Sextet from the music store. The curious clerk is actually playing the album when she walks in, and without knowing what she’s listening to, she realizes that she knows the music but can’t figure out why. Back at the office, Luisa finds out that she’s the only one who has been fired. She asks the owner, K.P. Ogilvy, and her editor, Dom Grelsch, if Seaboard happens to own the conglomerate who bought out Sypglass. Neither will answer, but their silence says enough for Luisa to know the truth, and to understand this means she really is on the trail of a massive story.

Meanwhile, Napier is ushered into a meeting with WIlliam Wiley, Vice-CEO of Seaboard, and Fay Li. He is offered a handsome early retirement package. Seeing it for what it means—favour has shifted and he is now a liability and not an insider—he takes the deal. Riddled with guilt and paranoia, he leaves Swannekke Island and heads to his fishing cabin. He stocks up on supplies and makes it all the way to the woods. But can’t sleep, plagued by fear that every sound he hears is the tread of an assassin. He reflects on his role in the Margo Roker assault: he was told by Bill Smoke that the old woman was not going to be at home and that they were just going to steal her files. Instead, as he stood watch, he heard her scream and found Bill Smoke clubbing her nearly to death in her own bed, implicating Joe as an accessory to the assault and making it impossible for him to go to the authorities. He decides in the present that he can’t let Lester Rey’s daughter keep putting herself in danger, and heads back into Buenas Yerbas.

Luisa reads about Lloyd Hooks’ move from Federal Power Commission to CEO of Seaboard. Back to her usual breakfast joint, the Snow White Diner, Luisa runs into Grelsch. Turns out it’s his usual breakfast spot, too, but she’s never seen him there because he leaves an hour before she arrives each morning. He explains why he allowed her firing to happen: his wife has leukemia, they’re about to lose the house because of the medical bills, and the new owners have agreed to pay for everything, including reimbursement of previous bills, if Grelsch stays on and keeps quiet about Luisa and the Sixsmith Report. He says he’s not ashamed of putting his own family’s needs first. Then again, he’s also not above putting Luisa in touch with another newspaper editor, just in case that story she’s working on happens to go somewhere.

Luisa picks up her stuff from the office, including a letter that was sent to her, which includes a key and a note from Sixsmith: the key is to a safe deposit box in a nearby bank, where Sixsmith has deposited a copy of the report. Luisa goes straight there, but not before Fay Li, still on the hunt for the report for her own purposes, arrives with two henchmen. Fay confronts Luisa and takes the key from her before instructing her goons in Cantonese to do away with Luisa quietly. But as Luisa is taken down the hall, she’s thrown to the ground by an explosion: it’s all a set-up. In a double- (or triple-, now?) cross, Bill Smoke has rigged the report to a bomb, and Fay dies in the explosion.

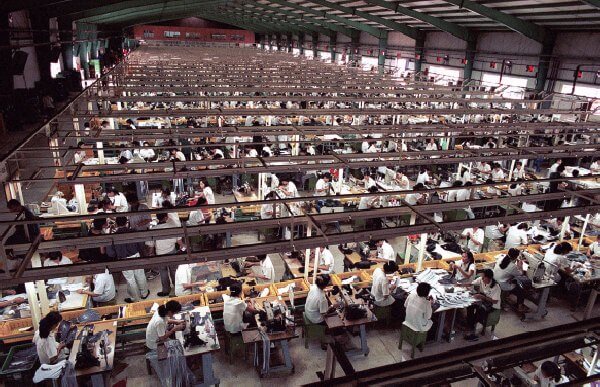

Dazed, Luisa is aware of someone trying to manhandle her into a car, but that someone is taken down with a baseball bat by Joe. He’s returned to save her, and they make a break for it on foot, Smoke and his two goons in hot pursuit. They duck into a warehouse, where they’re confronted by a Mexican woman claiming no illegal workers are on the premises. They go past her, farther into the building. Behind them, Smoke and his men appear in the building, and one of the men shoots the Mexican woman’s dog and calls her a “wetback” when she doesn’t answer immediately about Luisa and Joe’s whereabouts.

Luisa and Joe find themselves in a sweatshop, the dog-killer right behind them. Just as they think there’s no escape, the Mexican woman appears and clubs the killer into unconsciousness, in revenge for both the death of her dog and the racism. Joe suggests she tell the other assassins that he is the one who did that damage.

Safe for now, Joe takes Luisa to see someone who has flown in from Honolulu to see them: Sixsmith’s niece, Megan . Megan asks if her uncle was murdered, rather than having committed suicide, and Luisa confirms it. Megan tells them that Sixsmith had a yacht called Starfish he never told anyone at work about, and that most likely a copy of the report can be found there. Joe and Luisa go, finding the yacht moored near the Prophetess, a restored schooner, and of course the ship that Adam Ewing sails on in the first and last sections of Cloud Atlas. And Luisa once again feels a “strange gravity” as she passes the ship; her “birthmark throbs. She grasps for the ends of this elastic moment, but they disappear into the past and the future” (p. 430).

Inside the yacht, they locate the report, but Bill Smoke finds them before they can leave. He shoots Napier, but Napier manages to shoot Smoke, too, feeling that his debt to Lester is at last repaid. Both men die. At exactly the same moment, Margo Roker awakens in the hospital to find Hester Van Zandt beside her: perhaps their ending will be happier than Napier’s.

The story jumps forward a bit, to find Luisa reading about the aftermath of her scoop in the newspaper, the one Grelsch referred her to. She’s blown the story wide open, Lloyd Hooks has forfeited his $250,000 bail and fled the country, five Seaboard directors have been charged, and two have committed suicide in the wake of the scandal, Swannekke is being scrapped, and the country is safe from nuclear explosions and corporate corruption. Luisa is pleased that the story is now out of her hands and that she has a new job, and also that she has a letter from Javi: his mother has moved them into a nice house with a new man, and he sounds like he’s doing well. Also good, Megan has responded to Luisa’s request and sent her the second half of Frobisher’s letters. And now, safe, respected, and enjoying breakfast at her favourite diner, she settles in to read the next letter from Zedelghem.

Some Thoughts…

Again, I’m reminded of how chameleonlike David Mitchell can be. For some reason, the differences in writing style are striking me even more on the way back out of the stories than they did on the way through the first halves. Perhaps this is because I now know what to expect from each subsequent section, rather than being surprised as we move from one tale to the next.

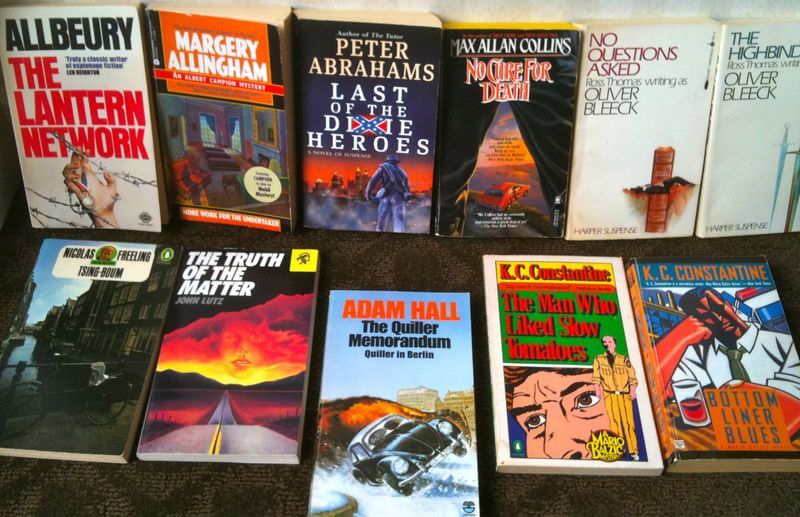

After a deeply suspenseful ending on the first half, we’re once again back into Luisa’s world of double- and triple-crosses. No one’s allegiance can be trusted, and none of the secondary characters is safe from murder (although Luisa, of course, escapes unscathed). The imagery is heavy-handed, with gems such as,”Water vapor rises from the Swannekke cooling towers like malign genies. Pylons march north to Buenas Yerbas and south to Los Angeles” (p. 396). The characters are almost entirely archetypal and cliched: the cop/security/guy/what-have-you who is only X months from retirement (Napier), the cool-as-ice assassin who takes great pride in the art of his deaths (Smoke), the grizzled-but-fair news editor (Grelsch), the turncoat who gets it in the end (Li). It’s got exactly the feel of a pulpy thriller that hasn’t yet had an editor help tone it down, going hand in hand with the Cavendish section to make us doubt what is “real” within Cloud Atlas and what is fiction.

Also heavy-handed in this section are the hints that Luisa is both Adam Ewing and Robert Frobisher reincarnated. Unlike in other sections, where the connection is fairly tenuous and sometimes not there at all, in this case Luisa’s birthmark “throbs,” and she feels a strange sense of import when she sees the Prophetess and when she hears the Cloud Atlas Sextet: Hilary V. Hush, the “author” of this section, obviously wants us to draw these lines in a way that David Mitchell, pulling the strings above Hush, isn’t as interested in doing in other sections.

There are some interesting inconsistencies of plot in this section, which I think have been put here to make it all the more obvious that we’re reading an unedited manuscript. Why, for example, would Fay Li bother to have a picture of Javi to threaten Luisa with, when she then immediately orders Luisa’s execution? The dun-dun-dun of Luisa’s death knell is just too pulpy for Hush to resist. Why would Bill Smoke go to the trouble of either breaking into a safe deposit box (and not just taking the report out), or setting up a safe deposit box with the oft-mentioned vanilla-coloured binder inside to make Fay or Luisa think they have the real report and then wire that report up to a bomb? Way too flashy, too time-consuming, and too messy when Smoke has already proved himself adept at making deaths look like suicides. Further, the package to Luisa arrives in the khaki envelope described in the first half, but in the first half Sixsmith mails her a key to an airport locker, one that the omniscient-ish narrator reminds us that characters walk right by without ever realizing its contents. So…is that a plot error? Did Smoke somehow intercept that package, switch keys, rewrite the letter to Luisa, and then send it on to set her up at the bank? Mitchell, I think, has deliberately riddled his “bad airport novel” with bad plot twists that make no sense, for the sake of suspense and cheap thrills.

Several characters wax poetic about the nature of time in this section, and Luisa herself makes a similar observation to Timothy Cavendish’s “lives crisscrossing” sentiment (p. 163) when she says “It’s a small world. It keeps recrossing itself” (p. 418). Coincidence? Tim putting those words in his own mouth as he writes his memoirs long after he first reads Half-Lives? Or something more?

Though Mitchell has gone out of his way to cast doubt on the validity of Half-Lives as a “true” story, the existence of the “Swannekke” people in Zachry’s time, and mentions made of Buenas Yerbas, do suggest that at least the geographical places exist within the future “true” stories. We certainly have a few interesting points of connection backward and forward outside of the very obvious Prophetess and Cloud Atlas Sextet references. Luisa’s mother Judith lives in Ewingville—named for Adam Ewing, perhaps? Megan Sixsmith is a radioastronomer in Honolulu. Perhaps she works in the temples of the Old’s that we see at the height of Mauna Kea in Zachry’s time. And the sweatshop that Luisa and Joe escape through is eerily reminiscent of the fabricants in Sonmi’s time, toiling away without adequate pay or working conditions, tucked away where society doesn’t have to think about their existence, doing the crap jobs that no one wants to do (and no one wants to pay proper money for). There isn’t a lot of difference between these illegal aliens and Sonmi’s sisters, at least in terms of their lot in life and the role they play in society.

Our theme of predacity is, of course, prominent here: Seaboard goes after Luisa very personally, corporation against individual. Many individuals actively hunt other individuals, Bill Smoke and Fay Li being the most prominent. Greed at the individual and corporate level abounds as well, in the form of Milton selling out Luisa to almost certain death in exchange for a payout, and of course in Seaboard’s insistence on going forward with the Swannekke project in spite of its dangers. We also have more of society’s inherent judging and distrust of others not like themselves: Fay Li invokes latent racism in the bank guard when she gets by him by speaking in “her most intolerable Chinese accent” (p. 420) and flashing ID the guard doesn’t even look at because it’s in “Chinese ideograms.” The Mexican woman physically strikes back against the man who calls her a wetback (and shoots her poodle). Luisa faces down mysogyny as people in her mother’s circle try to marry her off, express shock that she’s not married, and proclaim her a “bull dyke” when she rejects their advances.

As we talked about in the first half of the Luisa Rey story, the use of the limited-omniscient narrator is a departure from the other stories, because we get to see more of Luisa’s life and world than is evident in the other tales: the wealth of her family, the society world her mom lives in where snagging a husband is much more important than having a successful career, for example. We get to cheer for Napier as he makes the decision not to just retire into obscurity but to help Luisa; we get to see Grelsch justify putting his family’s immediate health before the possibility of nuclear disaster. We even get to see the happy ending of Hester and Margo, as Margo awakens from her coma at last. Because this is very obviously a novel and not excerpts from a journal or an interview, we get a much more finished picture. The bad guys get what they deserve. The good guys win. Who can say how much of this is “true”? We can’t ever know.

So what do you think about Luisa Rey’s tale? Do you buy all the of the plot twists? Do you think it’s “real,” or at least based on the truth?

You might also like:

|

TYPE Books’ Year of the Short Story: |

Sorry that I’ve only found this thread 7 years late but it’s the most comprehensive look at the Luisa Rey sections that I’ve come across. Perhaps Dee still monitors the page?

What I want to know is whether anyone thinks that Hilary V. Hush’s actual identity can be discovered using clues embedded throughout the novel. There are several such as the seemingly random Alain-Fournier reference but I haven’t been able to come up with an answer.

Mitchell seems to love games like this and I’ve been rewarded with several minor discoveries of the fun he has with his readers. Timothy Cavendish references …”Solzhenitsyn in Vermont” at the end of his narrative. I discovered that Solzhenitsyn spend much of his exile in a town named Cavendish. In the Adam Ewing section an Australian ship named Nellie is mentioned. When I googled “Nellie Australia” the first hit is Nellie Melba, a famous Australian opera singer and the daughter of famed builder “David Mitchell”.

Did anyone else think that Hilary V. Hush might be connected to Hester Van Zandt?

I agree that the bank job must have been consciously riddled with inconsistencies. In addition to what was said, why would Smoke want to prevent blood spilling on the report when he is about to kill Luisa on the boat? He alrady had access to a copy of the report from the airport/bank locker. No need to blow it up and hope for finding another one.

I found this section (like it’s first half) a lot of fun to read but it just doesn’t leave the same impact on me as other sections do. I had a similar thought about Smoke rigging up the file to a bomb. It was very exciting when I was in the moment of reading that section but the more I thought about it the more over the top it seemed. This section really did read like a pulpy novel at times which was both an excellent and not so excellent thing.

I think that the poem read to Margo by Hester should be discussed. It was ‘Brahma’ by Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of my personal favourites. The themes of the poem are heavily relevant to Cloud Atlas itself, including the similarities of things that humans percieve as different and the importance of mankind working in harmony.

Regarding the thought that Timothy cannot be a reincarnation of Luisa: How do we know this is impossible? Reincarnation is unproven, and thus has no hard established rules. Who’s to say that one’s soul cannot travel backwards in time upon death and take hold in a body that existed at the same time as a previous incarnation? If you die tomorrow at the age of 30, it’s possible your next life could be in the body of someone who was 13 at the time of your death. The soul is still housed in a “future” self because the next incarnation was born after the previous one.

I definitely agree with this point here. And I believe that Mitchell has hinted it in the near-finale of Luisa’s story. I don’t know if I’m the only one who finds this very remarkable, but I think that Margo MAY have been the reincarnation of Joe Napier. After Joe’s death at 21:57, the scene immediately transitions to Margo’s awakening at–oh what do you know–21: 57, as well! And Margo sure isn’t a baby. Hmmm….that scene has left an odd impression on me for quite awhile now.

I’m dying to ask – what did you think about the little girl who shows no emotion when her poodle is killed? What was the point of this… were we supposed to think this is maybe a clone, one who has no emotional development? The whole sweatshop scene seems an obvious reference to Sonmi 451, but I’m not really clear on what the little girl represents…?

Great question! I definitely agree that the sweatshop scene is meant to be an earlier iteration of the fabricant workers in Sonmi’s time. I take it from the brief description that she is perhaps not fully there, the way she stares at him “as if he were nothing more than a pleasant sunset.” From Hilary V. Hush, I think the little girl is another throwaway element of dramatic tension, a child who reacts in the opposite fashion you would expect to the violent death of her dog, or who has her own sad story that we don’t get to explore.

Were I Timothy Cavendish editing this book, I would want her cut entirely. I don’t *think* she’s meant to be an analogue or reference to anything else in the overall book, but I’d love to hear other people’s thoughts on the matter!

” I definitely agree that the sweatshop scene is meant to be an earlier iteration of the fabricant workers in Sonmi’s time.” yet it is clearly such a FABULOUS trope from those times – Hard Boiled-Cop, young audacious reporter, hard-core working-class backdrop. . . .

My impression is that Luisa, whoever she was, and her story were filtered heavily, yet convincingly for publication viewing the reception of the above Timothy Cavendish. They (whoever “they” were) needed copy and used what they could. Of course a lot of truth could be involved. . . . .

Weird side-note, but when I opened up Kindle Cloud Reader to re-read the Frobisher section, I noticed that the cover of the e-book in my Kindle Library had changed to reflect the new movie cover. Too bad – I liked the old one.

Oh, ugh. Definite downside to e-books.

Didn’t Tim mention that he edited the first half of the Hush novel he came across? Could the first half of Half-Lives we are exposed to be Tim’s edited version?

That’s possible, although it’s odd that he would leave the “reincarnation” element in there after mentioning that it was nonsense.

I got excited about this idea, but I think Brett’s right–if this were the edited version, Timbo would probably have axed the reincarnation “nonsense.”

I started reading the the 2nd half as if it was Timbo’s edited version. that would explain the plotholes since we didnt get to read his version of the 1st half.

VERY good

I’m re-reading it for a third time, since my last re-read was 3 weeks ago:

1. There’s an interesting Author’s Voice From On High moment when Sachs’ plane gets blown up, where it’s mentioned that the Actual Past and “Virtual Past” created from memories, fiction, etc will now start bifurcating. I didn’t quite notice that at first, but it probably explains why the second half of Luisa Rey seems so crazy – the “Virtual Past” in which the events occurred is getting farther and farther from anything resembling what actually happened.

2. You’d think the comments about Luisa going to her mother’s and counting on people thinking her dead would lead to something, but it doesn’t (a reminder of how poorly the Hush novel is written). She’s out and about among a bunch of rich corporate people at the party, and Bill Smoke actually shows up there (and doesn’t do anything). The whole thing is a plot dead end. .

There’s also no reason for her to suddenly show up at work and go music shopping like everything’s fine, either. She’s gone into hiding for her life, which lasts all of 30 seconds and doesn’t end in some sort of “No, I can’t live this way!” revelation but rather is, I think, forgotten…

Anyone for a little “Sextet”?

I love this chapter, even if I don’t like it as much as the Sonmi sections. It’s just insanely convoluted craziness, with nonsensical plot twists, in-your-face themes (not just the connection to Frobisher and Ewing, but the feminist theme too), and multiple double-crosses. It’s like Hillary Hush started out with a merely “mediocre” novel in the first half, the kind of book that would be considered second-rate Tom Clancy knock-off level, and then just completely lost control of the writing in the second half.

Since Cavendish is the one reading this, and he’s clearly writing his own autobiography to sell a movie, I wonder if the whole “bad guy acts racist and gets hit for it” is a plot element that he stole and thinly adapted into the bar scene in his story.

I absolutely adore the idea that Timbo is modeling his ghastly ordeal after this (and after how many other things, too?…). The way he ponders his birthmark, as if to make that important, even though he CANNOT be Luisa et al reincarnated because the timeline doesn’t work; the comment about the crossing/recrossing…As you said in the Cavendish second half comments, it’s doubtful that the deus ex machina of the pub people rising up to save Tim and his crew actually happened, or at least happened in exactly the manner he says it did. Perhaps he just got better enough that he was able to be released from the nursing home. Perhaps he’s still there, and his writing is how he copes with it…

When I first read this book a few years ago, I don’t remember realizing just HOW off the rails this second half of Half-Lives is. It’s really kind of an incredibly trainwreck to watch. Every time Napier thinks about how close he is to retirement, I feel like there must be a drinking game to go with it. Wonderfully cliched.

The issue with Cavendish being alive at the same time as Luisa is one of those things that makes me doubt that this all takes place in the same “reality”, even if the stories mostly line up chronologically. To me, Cavendish really feels like part of the “cloud atlas” soul, particularly since he shares many similarities with Frobisher.

It would also mean that Zach’ry would have to be part of it, and I think that’s wrong. His son even mentions that Meronym had the comet birthmark.

That’s a fascinating idea. Cavendish still being stuck in the retirement home and writing out his memoirs would be incredibly depressing. That would imply that his story was made into a movie presumably after someone (his brother?) found his memoirs after Cavendish himself died in the home.

It also makes a sickening kind of sense. Maybe in “reality”, he had the stroke, got put into the home, and he’s just completely losing touch with reality and fantasizing about a life and escape that he can’t really ever do. I wonder what Mitchell himself has said about this section.

That happened to be my total reading on his piece, a nuthouse case thinking he’s sprung free, even though he hasn’t. it’s still the most entertaining part

I’m not one for taking the reincarnation idea too literally, but just wanted to say that the way it’s written about throughout the book if it is even intended literally doesn’t seem to preclude the same soul existing as two different people at the same time (I’m thinking of Zach’ry’s cloud atlas ponderings here – I think you could reconsider the linear notion of time we have). I personally kind of see the reincarnation theme as another way to heighten the notion of the connection between all of us more than to be a thing to consider as explicit though. That said, which of us hasn’t had that odd moment of unusual feeling towards something or a strange sense of recollection? (Incidentally I am currently reading Frobisher part 2 again and am noticing his indirect connections to Ewing’s story much more on this read through.) Since I’m commenting on Luisa’s story – noticed so many references to other stories here – even silly throwaway things such as driving a Ford… It’s all so very clever! 😉

Oh yes, it appears I have begun to comment on all the blog posts now even though everyone else has been and gone 6 months ago. Depending on how you look at time… hahaha (oh dear!!!)

and which I experienced just now, hmmm…

You talk about some of the plot holes in the “pulp-narrative.” One of the things that confused me most about this story was how Bill Smoke and Fay Li new about the location of the Sixsmith’s file to begin with. Did I miss something?

It’s definitely an inconsistency. I think the idea is that Smoke somehow found out about the safe deposit box, whether he set it up from the beginning or whether he “hijacked” Sixsmith’s actual box, and told Fay Li about it. He must have known Fay would double-cross Seaboard, so figured he’d take out both pesky women with one bomb. But it’s a big logical inconsistency, and I think Mitchell is making the point that books like this sacrifice narrative quality for cheap thrills. There’s a reason you can’t put a down a Dan Brown book. He ends every very-short chapter with a cliffhanger…not unlike the way the first half of Luisa’s story made us all want to skip ahead and find out what happened to her. And while the first half is fairly sound, narratively, the second half is where the wheels come right off.

That’s part of Hush’s implied bad writing, I think. Not only does he have all manner of insane plot twists and double-crosses, but random stuff starts popping up with no logical events leading to it (like Li and Smoke somehow figuring out the safety box).

For that matter, the whole party at Luisa’s mother’s place felt jarringly out of place, like the section in the first chapter where everything comes to a halt so that we can get a few pages of her boyfriend moving his stuff out of her apartment.

I picture this as the kind of thing I see in the slush pile: a lot of ideas zooming around the authors head that haven’t been full thought out and plotted properly, or that shouldn’t be there in the first place. I can picture Timbo’s red pen circling things and crossing them out, asking for a reworking of the mother scene to make more comment on social stratification, perhaps, or crossing out the boyfriend entirely (he is, in fact, crossed out entirely in the movie…which I don’t think is enough of a spoiler to get me in trouble here!)

That makes sense. From what I’ve seen in the preview, it looks like Hanks-as-Isaac-Sachs has a bigger role than his weird passage through the story in the book.

I’m eagerly anticipating that movie, by the way. I know you said it was disappointing, but I would still like to see how they tried.

Oh, definitely see it. I’m eager to hear what other people think. I find the further into the readalong I go, the more disappointed I am in retrospect. That said, I know quite a few people who saw it at TIFF who were blown away by it.