Introduction

Part 1: The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing (first half)

Part 2: Letters from Zedelghem (first half)

Part 3: Half-Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery (first half)

Part 4: The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish

The Story So Far . . .

Cloud Atlas’ fourth part takes us back to a first person point of view as Timothy Cavendish writes his memoirs. Tim wants to tell the story of an ordeal that happened to him six years earlier. A sixtysomething, barely solvent vanity publisher in London, Tim starts his story by remembering an event he wasn’t planning to talk about, the time he was mugged by a trio of teenaged girls. Though this has little to do with the tale of his ordeal, it sets up two major components of this narrative: that Tim is old and is therefore treated poorly, and that he has a somewhat wandering style of remembrance.

Moving on to the story at hand, what he refers to as The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish, he prefaces the tale, by claiming that he had no idea what Dermot “Duster” Hoggins would do. Hoggins, a petty thug from a family of petty thugs, had hired Tim as his editor and vanity publisher of his fictionalized memoir, Knuckle Sandwich. On the night of the giant literary “Lemon Prize” announcement, Hoggins finds Tim in a pub with everyone else in British publishing, sees a critic who unmercifully butchered Knuckle Sandwich in a scathing review, and tosses the unsuspecting intellectual over the balcony to his death.

Hoggins goes to jail, but Knuckle Sandwich’s sales skyrocket, naturally, due to the public’s morbid curiosity. Because it was vanity-published rather than traditionally published, Tim owns the copyright and royalties outright and uses the proceeds to pay off his many debt-collectors. This means that when Hoggins’ angry and equally thuggish brothers break up in Tim’s house and demand their “fair share” (fifty thousand pounds) Tim has absolutely no means to pay them back. He can’t get the bank to extend any further credit, nor will his brother Denholme, a broke merchant banker who describes himself as “the mighty fallen” (p. 157) and no longer has the means to bail Timothy out. What he can do, however, is set Tim up in a hideaway until the coast is clear, or at least until Tim can figure out his next move.

Thus begins Tim’s journey, which takes up most of the first half of his story in Cloud Atlas. To King’s Cross he ventures, leaving his lone employee, Mrs. Latham, to hold down the fort. He has many trivial trials along the way, the type of thing that we all experience at one time or another, but that make his add up to make his journey a headache. He suffers through long lines, having waited in the wrong queue (the advance ticket line) and finding that the perfectly capable ticket seller will not sell him a ticket for today. The others in line won’t back him up, and Security believe the younger people in line over Tim’s protests that he has waited his turn.

Image from TownsendBooks.com

Finally on the train, Tim takes out one of the many new manuscripts that has been sent to him in light of his recent success with Knuckle Sandwich, a book by Hilary V. Hush entitled (you guessed it) Half-Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery. Reflecting on what a terrible title for fiction that is (a hint that perhaps it isn’t fiction?), Tim further comments on the fact that it’s been written in bite-sized, movie-adaptation-ready chapters, in an “artsily-fartsily Clever” style (p. 162).

In Essex, his train is delayed due to a missing driver and he must wait for a shuttle to Cambridge in order to catch his connection. It turns out he grew up in Essex, and he is struck by all of the ways time has changed it, for example a fitness centre standing in the place where he once made out in a barn with his first love, Ursula. He follows a path to the house where Ursula once lived and by peering through the window he discovers, to his shock, that she lives there still, a grandmother to a precocious redheaded child dressed as a witch. He is confronted by another costumed child wrapped in bloody bandages (so this must be Halloween or at least a Halloween party around the end of October) and he beats a hasty retreat.

Back on the shuttle to Cambridge Tim goes, and in spite of the delay being entirely the fault of the train company, his connection ticket is no longer good because it’s for the day before. He buys a new ticket, and gets stuck once again, this time due to mechanical difficulties, in Adlestrop. While waiting for his journey to continue, he’s offered a drag on a joint by a friendly Rastafarian, which messes him up so badly that he has no real memory of getting from Adlestrop to his final destination. Denholme has arranged for him to stay in a hotel called Aurora House. When he finally gets there, he signs the guest registry and collapses into bed.

It isn’t until the next morning, when he is confronted by a woman going through his things who takes away his keys and other valuables, and swats him across the face for talking back, that he makes the startling realization that he’s not in a hotel at all. Aurora House is a nursing home, obviously Denholme’s idea of a joke. He hasn’t signed a guest registry but papers committing himself to Aurora House’s care. He isn’t allowed on the phone or to leave the grounds. Most mortifying of all, when he tries to make break for it, he is captured by a man called Mr. Withers, who throws him over a lawnmower and canes him into submission. This is not just a nursing home. It’s an abusive nursing home. Nurse Noakes, Mr. Withers, and the rest of the staff will keep Tim there by any means necessary, and as he observes, no one will believe him that there has been a mistake: “You can see it, can’t you, dear Reader? I was a man in a horror B-movie asylum. The more I ranted and raged, the more I proved that I was exactly where I should be” (p. 179).

Back in his room (locked in against his will), Tim is visited by two of the residents, Gwendolin Bendincks and Gordon Warlock-Williams, heads of the Residents’ Committee. They implore him to settle in and stop rocking the boat. Echoing Nurse Noakes’ earlier sentiment, they tell him that the world outside has forsaken him because he is old, that Aurora House is his only world now, and that he needs to get involved.

Horrified at his own oldness and the helplessness of his situation, he goes through the rest of his day without much of a fuss. At supper that night, plotting his escape, “a chain of firecrackers exploded in my skull and the old world came to an abrupt end” (p. 181). Thus ends the section, and we’re left wondering what has happened to Tim (though also knowing, since he is narrating this tale six years later, that this cannot be his end).

Some Thoughts…

Though one of the more straightforward narratives in Cloud Atlas, more is going on under the surface than we might at first realize. Tim says he is writing out his memoirs in longhand, which re-establishes the claim of authenticity in this section that we saw in the first two but that seems to be missing in the Luisa Rey section. While “Half-Lives” seems to be a novel and indeed is presented in this section as a fictional manuscript, these events we’re reading about actually happened to Tim because these are his non-fiction memoirs. This, of course, calls into question whether the first two sections, which we’ve learned about through the Luisa Rey section, are indeed “real” or fiction.

In the company of Adam Ewing and Robert Frobisher, Timothy Cavendish almost immediately shows himself to be an unreliable narrator, starting off his narrative by tale us the wrong story, forgetting which summer it is he is trying to talk about, and making all sorts of protests that none of what happened was his fault. Like Ewing and Frobisher before him, we have only his word on what happened, only his take on the story. How much agency does he have in his own ghastly ordeal? It’s hard to say, but one would imagine that if he’d had any real business or worldly acumen, he’d have known that the brothers Hoggins would come calling in old debts eventually. (In the way he casually eschews any responsibility for his divorce from his wife, whom he disdainfully refers to as “Madame X,” we also see this weakness of character and inability to take the blame.) I also get the impression from Denholme’s angry reaction to seeing Tim, before he’s even asked for money, that he has had to bail Tim out on more than one occasion. The nursing home prank smacks of revenge, a revenge that’s the result of many years’ build-up of tension.

Of particular interest to me is that in 2004 when Cloud Atlas was first published, this was the “current” section, and in less than a decade, it’s been rendered quite firmly in the past. Note a few things: the lack of smartphones and social media, even in a curmudgeonly “These kids today and their technology” way (though there is one anachronistically ironic moment where Tim refers to book reviewers as “twittering” about the Hoggins murder, using the term as it was originally meant). Note also the fact that Tim is a vanity publisher, a creature that all but doesn’t exist anymore. There isn’t a single mention of self-publishing, which is a huge part of the publishing world today and has very much replaced vanity publishers.

As a narrator, Timothy Cavendish is, to me, quite reminiscent of Robert Frobisher. Both have a casual arrogance, a deep-seated belief in their own infallibility. His negative descriptions of the countryside he passes through on his journey away from his debt-collectors recalls similar disdain on Frobisher’s part during his journey from his debt-collectors. They both refer to their parents as “Mater and Pater,” and both seem to be in dire financial straits though they are from wealthy families.

As with each of the first three parts, we also have a ton of casual racism sifted into Cavendish’s narrative. Angry at the woman who won’t sell him a ticket because he is indeed in the wrong line (which he claims isn’t his fault), he refers to her as “Nina Simone” (p. 160) because she is black, and when confronted by a black security guard, he calls the man “a colored yeti in a clip-on uniform.” His is the racism of an elderly grandfather or great-aunt, the kind of off-the-cuff comments that we might call someone on if they were our own age, but which we often dismiss because the elderly “don’t know any better.” It demonstrates the xenophobia that Mitchell has highlighted in every section so far.

Unlike the sexism that Luisa Rey faces down, Tim’s battle is with ageism. Morosely, he reflects upon this discrimination: “Language, too, will leave you behind, betraying your tribal affiliations whenever you speak. On escalators, on trunk roads, in supermarket aisles, the living will overtake you, incessantly. Elegant women will not see you. Store detectives will not see you. Salespeople will not see you, unless they sell stair lifts or fraudulent insurance policies. Only babies, cats, and drugs addicts will acknowledge your existence” (pp. 180–81). A lot of Tim’s problems do come about because no one will help or believe him, because he is old and therefore assumed to be incompetent.

So we have these bigger systems of predacity occurring, the old being preyed upon by the young, and on the individual level, Tim preys upon Hoggins’ notoriety and the critic’s death to make money, all but steals the royalties from Hoggins, is tricked into going away by Denholme, falls prey to faceless corporations’ predacity in the form of the various train issues he faces, and then, most obviously, is forcibly constrained, stolen from, and beaten by the operators of Aurora House. The other residents seem to have settled into their confinement well, and Tim muses, “Prisoner resistance merely justifies an ever-fiercer imprisonment in the minds of the imprisoners” (p. 181). Almost everyone in this section is horrible to everyone else. The shining exception here is Mrs. Latham, Tim’s assistant, who takes care of the books (as he says, “the gnostic algebra of what to pay whom and when” [p. 152]), and who keeps Tim and his business in line, for reasons that even Tim doesn’t understand. He points out that he doesn’t pay her enough to justify her loyalty. Is something else going on with Mrs. Latham, or is she just a nice woman who enjoys her work?

The other major theme, ascent/descent, occurs here in the guise of the golden past, the “In my day, everything was better than it is now” mentality. Tim repeatedly makes these claims. Essex has changed, Cambridge has changed, it’s a travesty that a gym has replaced a barn about which he had good memories, the teenagers are crass, the trains used to run better, and on and on. To Tim, humanity has descended terribly.

A side-note, something I found interesting but have no idea the implications of: Timothy Cavendish seems somewhat obsessed throughout this section with Egypt. It comes up several times. First, he mentions the Nefertiti earrings he gave Mrs. Latham to mark her tenth anniversary with the publishing house, which he points out he got out of a bargain bin at the British Museum gift shop—establishing both that he didn’t get them in Egypt and that he is a cheap bastard who bought a bargain-priced gift for his “priceless” assistant. When he is confronted in the line for being a queue-jumper and is told to go back where he came from, he barks inexplicably “Do I look like a ruddy Egyptian?” (p. 160). When he thinks back on his love affair with the mysterious Ursula, on separate occasions he refers to himself as Tutankhamen and then to Ursula as Cleopatra. I’m not sure what to make of this, but it’s prevalent enough in this section that it’s worth the mention, at least.

Finally, this section is rampant with forward-and-backward looks at the rest of the book. Knuckle Sandwich is apparently available in “piles” at airport bookshops, and “Half-Lives” is supposed to be an airport novel. “Half-Lives” appears as a manuscript, which Tim derides and which he assumes is fiction (though we don’t know this for certain at this point). The fact that Knuckle Sandwich is supposed to be a fictionalized memoir speaks both to the nature of this section and of the Luisa Rey section. Are they fiction too? Is any memoir not a fiction of a sort?

Other references of note: a jazz sextet plays at the awards night, a meta reference to the sextet nature of Cloud Atlas as a whole. For the second section in a row (or possibly the third), the narrator uses the verb “sloosh” (p. 90, p. 155), and I wonder if this is an intentional reference to the upcoming middle section, “Sloosha’s Crossin’.” A deliberate forward reference, similar to Vyvyan Ayrs’ dream of the restaurant far in the future where all the servers had the same face, occurs as Tim notices how much Cambridge has changed since his day: “Cambridge outskirts are all science parks now…where those Biotech Space Age cuboids now sit cloning humans for shady Koreans” (p. 168).

Tim listens as “a howling singer on the radio strummed a song about how everything that dies someday comes back” (p. 171). And, though we have no direct suggestion of reincarnation here other than Tim’s similarities to Frobisher (no comet birthmark is mentioned), perhaps the most important passage regarding the cyclical, overlapping nature of time is provided by Timothy Cavendish: “You would think a place the size of England could easily hold all the happenings in one humble lifetime without much overlap—I mean, it’s not ruddy Luxembourg we live in—but no, we cross, crisscross, and recross our old tracks like figure skaters” (p. 163). You would think this world would be enough to hold all the happenings of many lifetimes, but apparently we are crossing and re-crossing our old selves, our past lives, again and again.

So, what did you think of this section? Did you enjoy it? What do you think of Tim as a narrator? As a character? Is Luisa’s story fictional, based on its place in Tim’s narrative? What is the purpose of the Egyptian references? What do you think of Mrs. Latham? What else do you think about this section?

You might also like:

|

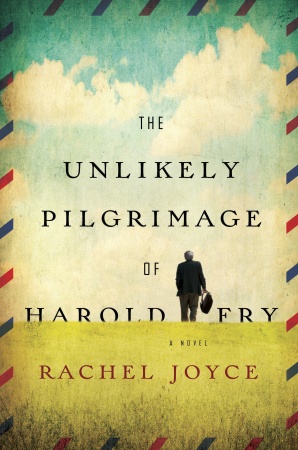

Review of The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, by Rachel Joyce |

The National Ballet of Canada’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland |

I know it’s been a whole year since you posted this, but I’m just about to finish reading Cloud Atlas for the first time. I’ve seen the movie, which is vastly different in some parts, and I’ve been trying to piece together this whole “reincarnation” thing as far as the book is concerned. I googled Cloud Atlas explained and that’s how I found your analysis, haha. The movie leads us to believe that Zachry is also a part of this string, although in the book it looks like it’s actually Meronym who is? Anyway, I wanted to comment here in particular b/c you say that Cavendish mentions no birthmark, but I think he actually does? On page 357 when he’s admonishing the idea that Luisa is a reincarnation of Robert, he says “I, too, have a birthmark, below my left armpit, but no lover ever compared it to a comet. Georgette nicknamed it Timbo’s Turd.”

I’m wondering what you think of this? Could it be a hint that Tim does in fact have the same birthmark as the others, and is just being cynical seeing as he thinks reincarnation is too “hippie-druggy-new age,” or does he just happen to have a totally unrelated birthmark that’s not the comet? I’m just curious about your thoughts on this! He also says, pg. 380 during his escape from Aurora House, that the car “shunted rather than moved because the hand brake was on…I flung away the sensation of having lived through this very moment many times before.” When reading Cloud Atlas I keep getting the distinct feeling that each character mentions these little “recollections” that tie back to the previous story (ie, further proof that they are supposed to be reincarnated). I can’t help thinking that this commentary from Cavendish is actually a memory of Luisa being driven off the bridge by Bill Smoke. Likewise, there’s more than enough evidence of Luisa being Robert’s reincarnation: the fact that Sixsmith says he feels like he’s known her for years, despite having just met; the fact that Luisa states implicitly that she KNOWS Robert’s music; and most notably to me, the fact that she’s terrified of guns. Seems a little too coincidental that Luisa is afraid of guns when Robert (her presumed past life) killed himself with one?

Then there’s Robert, who I’m sure had an experience that was like being on a ship (Adam), and Sonmi who I remember mentioning something that reminded me of Cavendish. I’d quote these passages properly if I could just find them damned things, but I’m certain they’re in here somewhere!

Anyway, thank you for analyzing each section of the story! I feel like I understand Adam’s way more now than I did when I actually read it, haha. And I couldn’t remember who had the birthmark in Sloosha’s Crossin’ until I read your review of the section. I wonder why Mitchell chose not to write it from Meronym’s perspective, like he did with the previous incarnations?

Though Cavendish is definitely an unreliable narrator (I love how he finds creative ways to blame others for his problems, rather than just see them as unfortunate accidents or his own fault) but I still found myself drawn to him. Maybe it’s because I work for a small publisher (not a vanity publisher but we still face challenges in getting our books “out there”) and I found that formed a sort of bond between us.

I also really liked the end of this story when he reaches Aurora House and doesn’t realize it’s a home for the elderly until much later and then he stuck there. His struggle to try and prove he didn’t belong there made me pity him and has kept me invested to find out what happens to him in part 2 of his story.

It’s funny. I didn’t remember enjoying this section nearly as much the first time I read this book, but Tim has become one of my favourite narratives in one of my favourite sections.

And his story gets more interesting…can’t wait till you read the second part of it!

I’m enjoying this read along. I saw the movie first, but now want to go back and read the book. I think the Egyptian themes were there to imply reincarnation in case the reader still wasn’t sure what the underlying theme of the story was by the third section. Why do these people have a similar birthmark? Not because they are necessarily related in a physical, or genetic sense, but in a metaphysical one. The metaphors in Could Atlas have metaphors! lol

I said third section but I meant the fourth section we’re in. =)

Indeed they do! Thanks for your comment 🙂

Hello,

I’ve just discovered this read-a-long blog and have been really enjoying it. I came across it because I was listening to the audiobook version (which is slightly abridged- why?), got about half way through and got really annoyed with the book. What is all this pretentious nonsense. Why don’t you just write in ruddy normal English, man. I was googling for a breakdown of the book and found you guys. Actually you really got me engaged with the themes of Cloud Atlas and I’ve now gone back to re-listen to the first half (ascent!), which has been very pleasurable now I know what the hell’s going on and can start to make links for myself. Am a little behind on the chapters but wanted to throw my penny’s worth in.

Picking up your comment Dee about the reference Tim makes to Ancient Egypt, I was wondering whether this is a reference by Mitchell to the structure of the book. It seems to me that the structure follows that of a pyramid (ABCDEFEDCBA), and with the themes of ascent, following by that of descent after the sixth story. This got me thinking and I started trying to connect others themes to Ancient Egypt and pyramids – the slaves that helped built the pyramids, how the pyramids were supposed to be aligned with the stars (observatory at top of mountain in story six), the reference to boats in the stories and the boats that were embedded in the great pyramids to take the souls of the dead (or something), the Egyptian idea that the soul double (ka) of the person leaves them at their death (a pair of earings?). There are apparently also some language similarities between Egypt and Maori.

On a different note, there also seemed to be a link within this chapter and the first – the similarity between Autua (the slave who knows too much, has travelled the world, escapes, is captured and flogged and cannot be constrained), and Tim (on the run from those he owes, escaping from his ‘captors’ and spanked). I also wondered about the breaking down of the trains and being stranded in places, much like Adam perhaps?

Anyway, this may all be me going off on a tangent and reading into it a bit much, creating another subjective story that has holes and may be unreliable – maybe that’s the point? It seems there are elements of the characters and themes which are repeated throughout the stories and also reversed (Sonmi having knowledge withheld, Meronym withholding knowledge). Top marks to Mitchell for making us think though.

Thanks for stopping by and commenting, Rom! I like your idea of the Egyptian themes as a nod to the metastructure of the entire novel. Good parallels between Autua/Tim and Adam’s ship/Tim’s trains, too. So many subtle points of connection, aren’t there? I love that they’re embedded throughout without ever hitting the reader over the head.

The first time I read this book, I had a bit of trouble settling into it because I didn’t like the Melvillian style, and I only stuck with it at the urging of a colleague whose reading tastes are similar to my own. I’m so glad I did, and I hope that this readalong might help others stick with it and discover the joys of this book too.

One of my favorite sections. I laughed out loud several times while reading. Maybe the story is exaggerated by his author, because people always tend to exaggerate while telling adventures of their life. I love Timbo and his tale.

And I think Luisa Rey first mistery is based on real events.

it’s funny, I didn’t remember loving Timothy Cavendish’s tale the first time through. It was overshadowed for me by some of the tales of grander scope. But upon this reading, I totally fell in love with it. I definitely agree that he’s exaggerating or possibly even falsifying some of the events, not unlike what we’ll see in Sloosha’s Crossin’, but I do think the bare bones of his tale happened to him.

The Luisa Rey question is, to me, one of the central mysteries in the. I think we’re meant to doubt whether it’s real or fiction, which casts doubt on the veracity of the other tales. He’s playing so much here with ideas of truth, storytelling, bias, and fiction. The author’s name, Hilary V. Hush, seems quite obviously a nom de plume, so who knows if this really is based on real events…we can guess, but we’ll never know! (The movie, if and when you get a chance to see it, takes a stand on this point. It makes a tiny alteration that I won’t spoil but it definitely doesn’t leave the ambiguity in place.)

To be perfectly honest, I wouldn’t be surprised if a ton of it is Cavendish making stuff up and/or grossly exaggerating his “persecution” in order to sell another hot “autobiography”. He’s clearly hankering for another publishing success along the lines of Knuckle Sandwich, which itself was probably self-serving.

There are holes in his story even from the beginning. He just happened to accidentally check himself into a nursing home, in such a way that he signed over any rights to leave of his own volition? His brother is broke, but has enough money to pay for him to stay there indefinitely (although this is the UK, so perhaps the NHS would pay for part or all of it)?

I never thought of it that way or really considered the plot holes in his story. I love how this idea throws his entire narrative into question, though! Certainly he’s made himself the poor, put-upon hero of his own tale, but it’s fascinating to consider that much of this might in fact be fabrication…

You know this may sound unusual but reincarnation was not something I was thinking about when I read the book the first time. I didn’t think of these people as reincarnated but more connected over space and time like something cosmic or even spiritual. But now that I am thinking more about the reincarnation thing, I am not sure at all how this story fits in the overall narrative. I am getting more and more curious about the movie!

I think David Mitchell quite deliberately leaves the idea of reincarnation ambiguous and tenuous. We don’t see the birthmark in every story, for example. He really shies away from any easy answers. I can see reading the book and seeing it more as connections and repeating patterns than necessarily as the overarching story of one soul’s journey. (I’ve now seen the movie, and I was disappointed with how they boiled the themes down and made them overly obvious.)

This was a ghastly ordeal! I enjoyed the storytelling immensely as I felt I was right there with him. Also I found myself laughing as he was telling what really is a completely harrowing experience. Apart from the Luisa Rey manuscript how do you see this story fitting in with other stories?

Good question. We don’t have the obvious connection of the comet birthmark in this story, nor any dreams or memories that really connect him to the other stories so far. I think this section is there to cast doubt on the proceedings, as much as anything. Within the context of the novel so far, each section has been “real,” and then we have Tim reading Luisa’s story as though it is fiction. This is a disconcerting thought. We’re emotionally invested and picking up threads and promises that we’re looking at reincarnated lives, only to be told that perhaps this is all fiction even within the confines of the novel. That Timothy doesn’t seem to be overtly connected to any of the other lives and stories also throws doubt onto the simplicity of the idea of rebirths. This isn’t meant to be an easy theme (and it’s one I fear has been oversimplified in the film, since many of the characters are wearing Tom Hanks’, Halle Barry’s, or Jim Broadbent’s faces for the purpose of visual storytelling).

What do you think is this story’s purpose or place in the overall narrative?

(A sidetracked thought…this actually leads me to wonder if anyone has done an analysis of Cloud Atlas through a Buddhist lens. Buddhists believe that we are made up of 5 skandhas, or aggregates, including physical form, perception, and consciousness, that come together over and over in each reincarnation, but are inherently without an eternal “I”….)

And I agree–I love Tim as a narrator. He’s a bit of a jerk, a bit of a prima donna, but so funny and so human during what, as you say, is truly a harrowing experience. It’s one of those wacky happenings that’s just crazy enough to actually happen to someone.