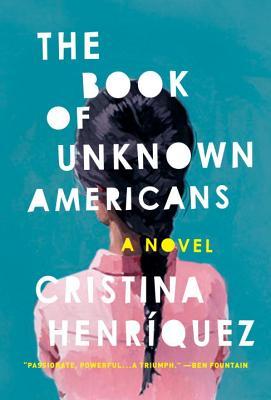

Different motivations prompt immigration to the United States in Cristina Henríquez’s ambitious novel The Book of Unknown Americans.

“I couldn’t help but think of how in Pátzcuaro Arturo used to come home at midday and sit at the kitchen table, eating the lunch I had spent much of the morning preparing for him. Soft tortillas that I had ground from nixtamal, wrapped in a dish towel to keep them warm, a plate of shredded chicken or pork, bowls of cubed papaya and mango topped with coconut juice or cotija cheese. . . And now this? This was where I had brought him? “

– The Book of Unknown Americans, Cristina Henríquez

Different motivations prompt immigration to the United States in Cristina Henríquez’s ambitious novel The Book of Unknown Americans. The Riveras arrive in Delaware from their comfortable, happy home in Mexico with the hope that their brain-damaged daughter Maribel will find help at a special school. The Toros emigrated years ago from Panama. They try to cope with alienation in their new and from their old ones, loss of identity and hope, while finding the profound importance of community.

Unknown Americans plays against the idea of America as the promised land for people running from social or political upheaval, or people running toward a shining dream of success in a different country. For the most part, the legal immigrants of the story have left loving homes, strong cultural and familial ties, and steady jobs, for an uncertain future. Henríquez alternates the point of view between Maribel’s mother Alma and the Riveras’ teenaged son Mayor to move the story forward, interspersing short interludes told from the points of view of other neighbours in the apartment complex.

Alma is an absorbing and beautifully drawn character. She blames herself for the accident that damaged her daughter’s brain, and in moving the family to Delaware so Maribel can get the help she needs, Alma also feels responsible for her husband Arturo’s predicament, working ridiculous hours in poor conditions at the mushroom farm that has sponsored the family’s visas. Her overprotectiveness of Maribel is both understandable and frustrating. Her terror at being unable to speak English or find her way around her new city is matched by her despair at having to stretch Arturo’s meagre salary to feed her family with cheap, bland food. Their tiny, barely furnished apartment contrasts poorly against her memories of their bright, warm home in Mexico, filled with delicious smells, laughter, and family. She is brave and frightened, loving and withdrawn, trying desperately to hold her family together even as she is sure it is her fault they’re falling apart.

The book is strongest in her hands and in the short one-off chapters told from the point of view of a different person. Each neighbour has come from a different Central or South American country for a different reason. We hear stories of people who came to be movie stars or wrestlers, who bought their way out of prostitution or who wanted to be priests. This also helps to flesh out the story, as we see, for example, the woman Alma find to be a meddling braggart and who spies on Maribel and Mayor, talking about why volunteering and keeping an eye on the neighbourhood is so important to her. This gently underscores Henríquez’s point—we’ve jumped to a conclusion about many of these people before taking the time to get to know them and see things from their point of view.

The story falters when it jumps into Mayor’s point of view. His voice, and Maribel’s, never quite find an authentic note, sounding much more like forty year olds than fifteen year olds. They speak to each other as though reading lines from a play, and while the romance that develops between them is sweet, it’s troubling never to see it from Maribel’s side. The villains of the story are likewise lacking in dimension—it’s obvious from the beginning who the bad guys are, and they act like bad guys consistently. The plot feels mechanical, which makes for a predictable climax that is neither shocking nor as emotional as it should be. Ultimately, the tension and pacing don’t find their footing.

The book succeeds and fails on the strengths and weaknesses of its characterization. When it’s good, it’s very good. A quick but thought-provoking story about how “the immigrant experience” is not one homogenized thing but contains multitudes, The Book of Unknown Americans is a worthwhile read for the voices it gives a voiceless—or ignored—segment of the American population.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Three and a half out of five blue pencils

Three and a half out of five blue pencils

A copy of this book was provided to me by Bond Street Books in exchange for an unbiased review.

The Book of Unknown Americans by Cristina Henríquez, published in Canada by Bond Street Books, © 2014.

Available at Amazon, Indigo, and at fine independent bookstores everywhere via Indiebound.

You might also like: