The Luminato Festival has always had strong visual and performing arts components. This year also features a more robust literary program, celebrating the art of the written word. On June 11th, 2014, the Toronto Reference Library’s Appel Salon hosted a unique round-table event: #ReadWomen2014 Luminato.

|

|

|

|

The #ReadWomen2014 hashtag for Twitter was created by author and illustrator Joanna Walsh as a year-long celebration of women writers. The parameters are flexible as readers shape what exactly #ReadWomen2014 means to them. The hashtag has been promoted by bookstores, publishing houses, literary critics, and readers. Issues have ranged from the Vida count and CWILA count to the “girly” covers for books that happen to be written by women (See Maureen Johnson’s coverflip challenge from last year), celebrations of women writers’ awards, and recommendations of women writers’ works. Luminato has joined the discussion with its #ReadWomen2014 panel, featuring Lisa Gabriele (The S.E.C.R.E.T. trilogy as L. Marie Adeline), Heather O’Neill (The Girl who was Saturday Night), Elizabeth Renzetti (Based on a True Story), and Miriam Toews (All My Puny Sorrows). A mix of readings, round-table discussions about writing and motivation, and Q&A, the evening was moderated by Luminato’s Literary & Ideas Curator Noah Richler. “So why gather these four great novelists?” Richler asked. “If only for the company!”

Write what you know

Richler began by asking each of the writers their thoughts on the old adage “write what you know,” and how much of their writing is influenced by their own experiences. Lisa Gabriele, who has written and ghostwritten works of fiction and who writes erotica under the name L. Marie Adeline, joked that S.E.C.R.E.T. does not reflect “the bloody boring life of erotica novelists. . . it’s sad, really!” But choosing to write from the point of view of a struggling single mother in one of her books and a successful African-American journalist in another taught her how little she knew about other people’s lives. While she could identify with much of her black character Solange Faraday in terms of career and ambitions, she asked her best friend, who is black, to read Solange and help her with authenticity. The book “does feel very organically a part of me, a sieve through which I push part of myself.”

Elizabeth Renzetti spoke of “knowing” in other ways: “I’m a huge alcoholic and have taken every drug” she joked, referencing Augusta Price, the larger-than-life actress in her debut novel. In reality, as a journalist who has worked in the Globe & Mail‘s London bureau, she was influenced by a number of UK memoirs that were by or about people who hadn’t really done anything of note. She was interested in “the selective way they chose to remember their lives” and the reasons people have for writing memoirs, in “truth and fiction and what lies in between.”

From a lower-class neighbourhood of Montreal and growing up with a sense of shame for her family and herself, Heather O’Neill was worried about being looked on as just a statistic. She wrote Lullabies for Little Criminals in order to examine that place and to explain the beauty she found in her life, what was worthwhile. She wanted to create a character and a neighbourhood that people would love; in writing her character Baby, she wanted to keep “true to how I saw the world s a child…a dark novel, written in the alleyways, staying in the alleyways.” When she gave it to a Quebecois friend to read, she was told “Oh, that’s fantastic, but you realize they’re going to kick you out of Quebec!”

Miriam Toews, whose novels are all influenced by her life, and whose latest All My Puny Sorrows is a coming-to-terms with the real-life suicide of her sister, said of writing what you know, “It does make sense to me, but on different levels.” Certainly writing what you know requires little research, and allows you to “add some juice and call it fiction,” but she prefers to discuss the idea of why we write: “we’re trying to make sense, process, create an emotional truth we can live with.”

On why we write

With the rise of books like 50 Shades of Grey, and after several ghostwriting projects that felt like work, Lisa Gabriele wanted to write something fun, a different kind of erotic world from what has been popularized in the last couple of years. She wanted the gender politics she cares about to be reflected in this work, to play with the physical tropes and to tackle issues that weren’t being addressed. She created a world in which her women characters have sexual agency. It’s not about getting the guy. “So I pumped it out,” she said, grinning mischievously. “For lack of a better word. It just came….it was a hard job.”

Elizabeth Renzetti quoted Farley Mowatt: “The only pleasure in writing lies in its cessation.” She wanted to push past the limits placed on journalists, where “You’re not invited to project yourself into the mind of the people you’re writing about.” Heather O’Neill starts first with characters whose stories she wants to tell. In The Girl who was Saturday Night, she wanted to explore ideas of separation and destructive love from the point of view of “over-the-top” twins whose lives are enmeshed, so she decided to look at this question of separation against the backdrop of Quebec trying to leave Canada.

Noah Richler asked if the act of writing to deal with her sister’s suicide “satisfied” Miriam Toews at all. “In the moment,” Miriam responded. “It’s a way of giving meaning to events that were chaotic and ugly.” Her writing became “a reinterpretation, with beauty and a hopeful feel.” She hopes that the book can be “a living, breathing document, a manual of survival,” but satisifed? No. There can be no satisfaction, ultimately.

The subversive

In Miriam Toews’s books in general, a subversive element can be seen at work, pushing against patriarchy, but in this one, Miriam sees the subversive element simply as the act of talking about and acknowledging death, of helping someone labelled mentally ill or depressed so they won’t die “alone violently, with deep shame.” Lisa Gabriele’s subversive element, meanwhile, lies not so much in the erotic elements of her story as in the discussion of women’s bodies and agency. Erotica “is a new genre full of old ideas,” she said, which is why she included a subplot about a teenaged girl being bullied into a suicide attempt because she has had sex. Women are still frowned upon for either having sex or not having sex, and she wanted to challenge that notion.

Women, writing, and public reaction

Bringing the hour-plus discussion of writing in general around to the topic at hand, that of being a woman writer in 2014, Noah Richler asked about the panelists’ experiences with sexism in publishing. Lisa Gabriele, who reads and writes both “serious” works and erotic works for women, says “I read all sorts of books for pleasure. A s a reader I would go to those books for different reasons.” She tries not to read criticism that comes from “a bad, dark place. I try not to shit on what other people read.” The audience burst into applause at that.

While Heather O’Neill does not pay attention to critics who approach her work with negative gender stereotypes, Miriam Toews pointed out, “Are male writers asked ‘Was writing this book therapeutic for you?'” Or are women writers continually brought back to a place of emotion in a way that men are not? Elizabeth Renzetti pointed out that when men write about interior lives (think Jonathan Franzen), it’s always assumed they’re writing about something bigger. When women write the same, it’s dismissed as a “domestic novel.”

Fast-paced and funny, the evening made for wonderful discussion and offered great insight into who, why, and how we read and write. The choice to keep the questions general until the last ten minutes was a bit odd. Had the event been about writing and happened to feature four women writers, the tone would have been perfect. For an evening that was part of a hashtag movement specifically about discussion of women writers and the problems they face, this did strike a somewhat timid note. Addressing more issues would have been more in keeping with the activist part of #ReadWomen2014. But the celebration of these wonderful women writers was a joy to be a part of.

You might also like:

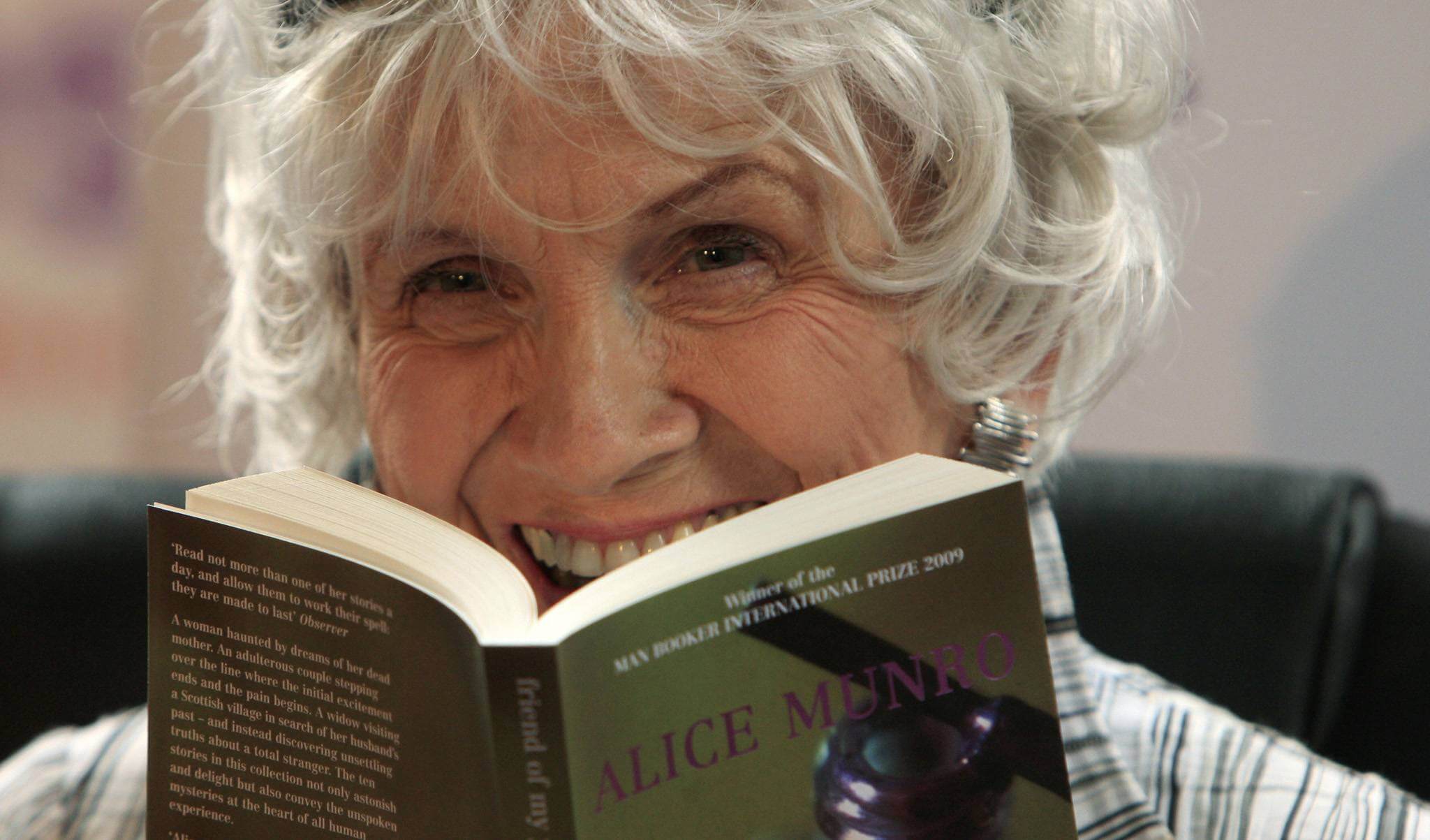

The IFOA’s Tribute to Alice Munro, |

I went as well. It was a great discussion and venue!

This sounds like it was a fascinating event! I wish I could have gone. I’m not familiar with Lisa Gabriele and Elizabeth Renzetti’s writing but I love Heather O’Neil and Miriam Toews books.

It was a great night! Like you, I only knew Heather O’Neill (though I haven’t read the new one yet) and Miriam Toews, but this definitely made me add Lisa Gabriele and Elizabeth Renzetti to my TBR pile!