Previous readalong posts

Read Part 1: “Introduction” & “Warnings”

Part 2: Blame

The Story So Far…

In Langley, Virginia, USA, the director of the CIA Bob Archer welcomes the interviewer into his office. Archer talks about the mythical status the CIA has enjoyed as an agency of master spies who knew everything going on around the world, in every country abroad and in every home in America. They propagated that status because it created a paranoia that kept people in line, even though their reach couldn’t possibly extend that far due to budget constraints. But still, Archer says, everyone blamed he CIA for not anticipating World War Z. He credits the Chinese with “the greatest single Maskirovkas in the history of modern espionage” (loc 812), i.e. claiming that the massive “Health and Safety” sweeps they were doing when the outbreaks first started were part of a dissident crackdown and not a major health crisis.

He also blames the purges in the CIA for the lack of intel on the disease: after the last, prolonged brushfire war, the American public was exhausted and a number of CIA employees took the fall, causing the smarter among them to jump ship to the private sector in order to avoid the witch hunt, and causing a brain drain. The interviewer asks if Archer had suspicions about what was happening in China. Archer did indeed, but his doubt was brushed aside, and the Warmbrunn-Knight Report wasn’t seen by anyone in the CIA until after the Voluntary Quarantine in Israel.

In Vaalajarvi, Finland, the interviewer notes that it is “hunting season,” spring, when the corpses frozen in winter reanimate with warmer weather and the UN N-For, or Northern Force, does its annual “Sweep and Clear.” The interviewer is there to speak with Travis D’Ambrosia, Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, who doesn’t deny that the US made mistakes at the beginning of the Great Panic. Like Archer, he and the people he worked with hadn’t read the Warmbrunn-Knight report, but they did have suspicions before the Israeli announcement. He says the joint chiefs had had a similar plan to the report: Phase One included the “Alpha Teams,” which Stanley MacDonald referred to in Part 1. These were attack forces whose “orders were to investigate, isolate, and eliminate. . .with extreme prejudice” zombie threats throughout the world (loc 882). This was a cheap, big-win phase and the government backed it, but D’Ambrosia says it was meant only to be a “stopgap” until Phase Two could be put in place. The government didn’t okay Phase Two, which would have “required a massive national undertaking, the likes of which hadn’t been seen since the darkest days of the Second World War” (loc 890). Like Archer, he stresses the American public’s weariness and impatience with war. It wasn’t a politically feasible move to make at the time. In democracy, he points out, you need the good will of the people on your side.

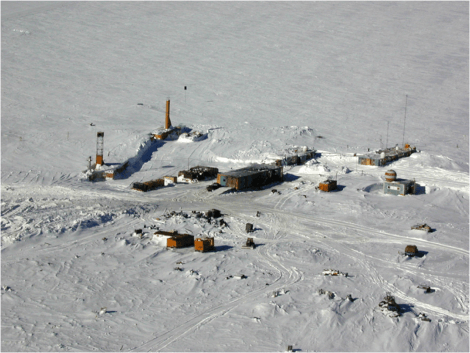

In Vostok Station, Antarctica, the interviewer visits a man who has been leasing this remote, nigh-impenetrable place from Russia since the Great Panic. Breckinridge “Breck” Scott waxes poetic about how capitalism works. “Fear sells,” he tells the interviewer, and he made his fortune based on that, selling a vaccine for rabies when reports began to circulate that the outbreaks in Africa were a type of that disease. He is pleased he didn’t have a cure. Vaccines, he says, are much more lucrative. “Phalanx” was fast-tracked through the FDA, “one of the most underfunded, mismanaged organizations in the country. I think they were still high-fiving over getting Red No. 2 out of M&Ms” (loc 949). He likens Phalanx to the flu shot, stressing that he and his company were selling peace of mind and that they never lied: “they told us it was rabies, so we made a vaccine for rabies” (loc 974). He also sold things like air purifiers even though the disease was never airborne, and so on, using public fear, gullibility, and ignorance to line his pockets. He claims that his vaccine kickstarted the flagging American economy, ending the recession (that growth itself ending when a particular reporter broke the story that a wonder drug didn’t actually exist). He seems to show no remorse, though he giggles at the end, perhaps nervously?

In Amarillo, Texas, USA, we meet Grover Carlson, a fuel collector for bioconversion plant. As he collects dung, he confirms that as chief of staff to the president of the United States at the time of the Great Panic, he of course saw the “Knight-WarnJews” report. The administration read it three months before the Israeli Voluntary Quarantine, but saw it as alarmist and far too expensive. Because the disease was assessed as a low priority, the government authorized the Alpha Teams and pushed Phalanx through, but did nothing more. “Do you know how long it would have taken to invent one that did?” he says when the interviewer points out that Phalanx didn’t work. If they’d allowed Americans to know what was really going on he says they’d have lost valuable political capital. Of course they never tried to “solve” the problem, he says, likening it to poverty, crime, and disease: “in politics, you focus on the needs of your power base. Keep them happy, and they keep you in office” (loc 1042).

He seems to blame the police, the “wet-pants senators,” and the media for trying to take power away from his administration and for being alarmist and spreading panic. He also claims that he was never part of a cover-up, that the media covered it up by themselves, and that any real news reported by “alternative media outlets” was only heard by “pansy, overeducated know-it-alls” (loc 1059). He stands by the claim that the administration gave the problem the amount of attention they thought it deserved, even after receiving dire warnings.

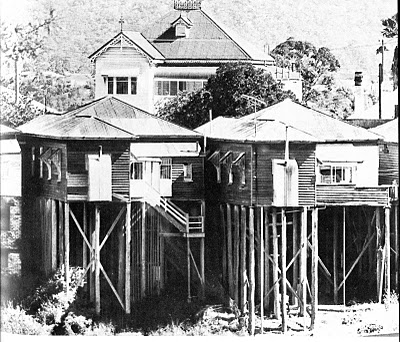

In Troy, Montana, USA, mayor Mary Jo Miller presides over her “New Community,” based on the Israeli Masada model, a town on stilts with serious security measures. She sounds like she was a typical upwardly mobile, upper-middle-class, unhappy woman: husband cheating on her, 401(k) issues, kids a drain. She was “too busy” to notice the news, and the beginnings of the Great Panic hadn’t really permeated the local gossip. Though her kids began to act out due to stress and fear, she was in her own world. She medicated them both for their anxiety issues, put everyone on Phalanx as a precaution, and continued going about her daily life. It wasn’t until her family was attacked that she realized this was a serious threat. A zombie came through the window: “it was about five foot ten, slumped, narrow shoulders with this puffy, wagging belly. It wasn’t wearing a shirt and its mottled gray flesh was all torn and pockmarked. it smelled like the beach, like rotten kelp in saltwater. . . In a split second, it was like all the lies fell away” (loc 1136). Though she claims not to remember it, her children say she ripped the head off a zombie menacing her daughter, and she and the children escaped, leaving her husband to fend off the zombies so they could get away.

Some thoughts…

We’re getting more of a sense of the structure and timeline of the world into which this plague arrived. Everyone at high levels was at least aware of the Knight-Warmbrunn report, even if they ignored its warnings or didn’t read it in the first place. People at those high levels of power, at least in the US, were aware that something was happening, long before it was admitted. Was there a cover-up? The people interviewed here deny it, but these people are also out to save their own reputations by telling their own highly biased take on history (and isn’t that what history is in the first place? By pulling together so many different firsthand, perhaps unreliable, accounts of what happened as it happened, the interviewer is almost creating an anti-history, a disparate collection of opinions and remembrances that may not all support one particular version of history). The US was in a recession and was just out of a brushfire war—perhaps the one now happening in the Middle East? Perhaps one in the very-close future? The appearance of African Rabies and the Israeli Voluntary Quarantine are universally accepted markers of the real start of the Great Panic, of everyone beginning to realize what was happening in the world.

Several themes are prominent in this section, which is all told from American perspectives: the head of the CIA, a member of the joint chiefs, the creator of a fake vaccine, a White House chief of staff, and a suburban mom-turned-survivor-turned-mayor. And with the exception of D’Ambrosia, none of these are terribly good people. They each display their own kind of brashness, arrogance, almost pride in the ignorance they had before and even during the Great Panic. Though D’Ambrosia is aware that between various government groups, the government let the American people down, the others defend their actions even today, a decade after VC Day, twenty years after the Great Panic. Grover Carlson, the former chief of staff, is particularly odious. A foul-mouthed, racist, sexist jerk, he is still trying to make the same political point he was holding to before the Great Panic. It’s apt that he’s seen by the interviewer literally shovelling shit. He’s certainly doing so figuratively as he blusters about all of the things his administration did correctly.

Carlson also raises some interesting questions about government. With the tide of popular opinion turned against wartime thinking, including precautions taken at home on the financial and practical level that Phase Two would have demanded, could the government even have implemented these measures if they’d tried? Would they have been voted down, even voted out of office? D’Ambrosia agrees with Carlson on this point: “In totalitarian regimes—communism, fascism, religious fundamentalism—popular support is a given. You can start wars, you can prolong them, you can put anyone in uniform for any length of time without ever having to worry about the slightest political backlash. In a democracy, the polar opposite is true. Public support must be husbanded as a finite national resource” (loc 894–902).

That said, there are mentions of China’s sweeping measures to stem the spread of the disease, measures made by a totalitarian regime and obviously to the detriment of human rights, including what would be illegal searches and privacy breaches in the US, not to mention mass executions. And yet China is, it seems, where the plague started. So this isn’t just a problem of political approach.

Still, Brooks is presenting a scathing indictment here: of governments more worried about re-election than the good of the people; of government agencies too concerned about empty coffers or too behind the times or laden down by the wheels of bureaucracy; of individuals only too happy to make a profit off others’ fear by using capitalism exactly as it can be used (not by gaming the system, per se, but simply by knowing how to make a buck off the public); and, just as bad as the others but on a more microcosmic scale, of our own personal blindness. I found Mary Jo Miller offensive and totally believable as a self-absorbed suburban nightmare, not aware of anything happening outside her borders—not just outside the country but even outside of her own airheaded first-world-problem-filled priorities. She is already a zombie of a type before the Great Panic, an example of the lackadaisical, deliberately ignorant NIMBYism that allowed the others in this section and the agencies they worked for to get away with their many, many failings.

And of course, the more things change, the more they stay the same. Scott may have made his bajillions by selling the public medicine they didn’t need that would never protect them from the zombie plague spreading across the globe, but someone is now making money by building these “Masada” towns that Miller is mayor of. Are these towns necessary? Would their security measures work if there were another outbreak? We don’t know, but the builders operate on the same principle that Scott does: fear sells.

Everyone is more than ready to point fingers elsewhere and to defend their own actions in this section, but seems no one is blameless.

Please feel free to leave thoughts about the readalong or the book so far!

You might also like:

|

Review of The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, by Rachel Joyce |

I’m trying to remember if I’ve ever read a book of interviews before: have you? Being a reader who loves stories told through letters and diaries, this doesn’t seem that different in some ways, but it takes out the immediacy those forms offer. It reminds me of reading stories that use footnotes in a creative way, providing the reader with more information but the author is taking a step back even while revealing it.

This section read more quickly for me; perhaps because it’s homogeneous with its American respondents. But, then again, I just checked the page counts, and it was a shorter section anyhow! i’m looking forward to the next segment, and soon I’ll be “caught up” with your schedule.

I love, love, love this book. It was completely different than what I was expecting, but offered up a few home truths about human nature and our will to survive.

Me too. I was not expecting a political allegory. I just finished the Cloud Atlas read along, which I really liked, and I was surprised to see this choice. But I am halfway through the novel, and I understand the appeal. It’s easy to find parallels (Animal Farm?) but Brooks stands up well on his own terms.

We know that mankind survives (don’t we?) but the road ahead is very uncertain at this point.

The political and social observations throughout are fascinating. Really, this could be a story of any fast-acting infection spreading across the globe, and it’s a considered examination of how humanity might react.

This is definitely a different read (and readalong) than Cloud Atlas! More of a summer blockbuster than a deep philosophical read, but still interesting, I hope. Thanks so much for commenting and reading along.

Totally agree. It’s much more serious and intelligent than I was expecting when I first picked it up (after seeing the movie trailers). Thanks for stopping by, Nicole!