|

|

|

Guy Gavriel Kay has been writing epic stories for many years. From the high fantasy of The Fionavar Tapestry to magic-tinted analogous histories in Tigana, A Song for Arbonne, and The Sarantine Mosaic duology, Kay’s style weaves together sweeping narratives with poetic, pitch-perfect writing.

In his new book, River of Stars, now available from Penguin Canada, Kay returns to the land of Kitai, which he first introduced in Under Heaven. In a setting based on Song-Dynasty China, we meet the ambitious warrior Ren Daiyan, a second son who wants to win military glory and take back lands long lost to Kitai, and Lin Shan, a woman educated by her father in a way that only boys are allowed. Poet, songwriter, and thinker, Shan must navigate a society that wants her to be much less than what she is. As the face of Kitai shifts once more, as war looms and “barbarians” encroach, Daiyan and Shan move and are moved by the currents of history. . .

I have always been fascinated with the way you tell stories in worlds close to our own but a little removed: something like medieval Italy in Tigana, Moorish Spain in The Lions of al-Rassan—a world you revisited in the Sarantine Mosaic duology — medieval Provence in A Song for Arbonne. Can you talk a bit about how you choose time periods and geographies, and why you set your books in (historically accurate and meticulously researched) analogues rather than the actual historical places in our own world?

Huge, very good question. I’ve done speeches and essays on this, so a sound bite is hard! Certainly there is no rule or formula for “where I go” in a next book. So far (knock wood) I seem to always end up with a time and place that fascinate me. I do that “quarter turn to the fantastic” for many reasons (see “speeches and essays,” above!). One is that I am not happy about pretending I know the innermost thoughts and feelings of real people. I don’t like “piggybacking” on their fame (or even taking obscure people and allowing myself license from that obscurity). I find it creatively liberating and ethically empowering to work in the way I do. There’s a shared understanding with readers in this: that when we explore the past we are always inventing, to a degree. I also like how a slight shift to the fantastic allows me to sharpen the focus of the story towards those themes and elements I want the reader to experience most clearly, and I can even change things, keeping even those who know the history on their toes!

Several centuries have passed since the events of Under Heaven, and the empire of Kitai is much diminished, though still large and powerful. You based this on the Song Dynasty before and after its sacking by the Jin Dynasty and the loss of its capital. How did you decide that this was the time and place you wanted to explore?

It is a terrifically powerful time and place, Dee. And encompasses so many of the things that draw me in terms of history. One of them is almost post-modern: that dynasty was itself fascinated by China’s own history. It shaped itself through an obsessive response to some major events of the past. . . and that notion is something I found very powerful as something to work with. Add some truly magnificent real figures to be inspired by, and room to introduce some of my own. . . the setting was a gift!

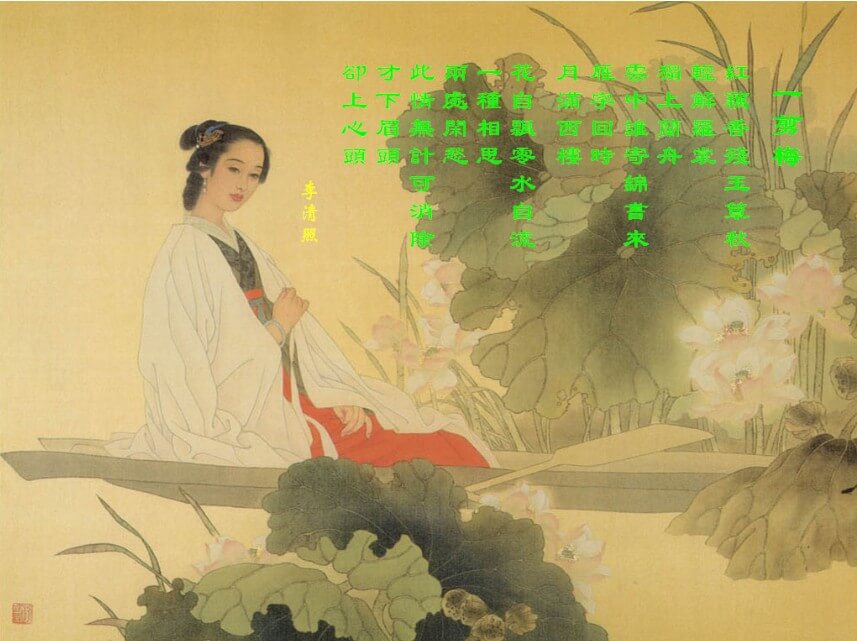

Tying into that question, your central figures, General Ren Daiyan and the poet Lady Lin Shan are based on, or inspired by, historical figures. I’m not terribly familiar with Chinese history myself, so after I finished your book I did some digging and read a bit about the real-life general Yue Fei and the celebrated female poet Li Qinzhao. How do you choose who will play a part in your sweeping epics? How do you decide what of their historical nature to incorporate into your characters?

These two emerged fairly early in my research and correspondence as likely to be major figures. They shared something that quickly became a theme of the book: the idea of people fighting hard against the rules, norms, constraints of their world. And I am always looking for ways to explore the status (or lack of it!) of women in history. Lin Shan gave me tremendous scope for doing that with a degree of accuracy. I don’t try to incorporate guesses as to “what they were really like”. . . that, as I said above, is central to how I write. I acknowledge that we can’t really know. There are some exceptions, as Li Qingzhao left behind her a great deal of (wonderful) writing, and I have made use of that. But the relationships among characters are not historical. This is why it is Kitai, not China!

Stories and legends from Under Heaven permeate the world of River of Stars, though each book stands alone. Did you enjoy playing within the world you had already created, nodding toward the lost Kanlin warriors, having Lin Shan explore the ruins of the old capital of Xinan? How did the first book inform the crafting of the second?

It seemed necessary, proper to do that, given the obsessive backward-looking nature of the society I was working with. Yes, it was an interesting challenge. Partly because the new book is meant to absolutely work for readers who have never even heard of Under Heaven! My psychoanalyst brother has suggested that in his profession, one would start with the newer book, “the present” and then go back and explore the past. I’ve written “Time runs both ways. We make stories of our lives.” and his insight fits these books very well. You can go either way in terms of sequence.

Daiyan and Shan’s stories form the backbone of this book, but many different stories come together, many different stars form the overarching river. Even those with minor roles are paid attention and given respect, and the reader is treated to glimpses into the backgrounds and motivations of many different people in Kitai and the Steppe. Can you talk a bit about the variety of minor characters, how you choose whose stories will, in part, be told, and the choice to give the reader these stories along with the larger ones that form the greater part of the tale?

Someone once wrote “Kay’s never met a secondary character he didn’t like!” and I have to admit it is mostly true. I may not like some of them, but I am interested in all of them, and want the reader to be. As a reader myself I am often frustrated with books that feel “thin”. . . I wanted Kitai, the empire, the setting, to become almost a character for the reader. I want you immersed deeply in it, and that requires not just as vivid a sense of place as I can manage, but also a cast of characters to fill it, people you come to care about, even among very minor ones. I always think of Shakespeare, actually: his genius for moving between a courtly setting and the simplest figures. I try, as best I can, to give some of that range.

Can you talk about the shift in your writing from high fantasy and worlds of magic in the Fionavar Tapestry and Tigana toward more historically grounded stories? Though a hint of the supernatural appears in the form of the Fox-woman and in discussions of ghosts in River of Stars, I don’t know that “fantasy” is necessarily the correct category for this work.

As we grow older our interests and focus often change (I’d say: they should!). Over the years my initial fascination with myth and legend has been paralleled and even outstripped by a love of history and a desire to explore the way it impacts on the present day. The supernatural in the last several books has served a major role for me in one way: I want to create settings where the world is as the people of the time understand it to be. I don’t want any modern smugness about the past. (You know: “Can you believe the silly things ancient Byzantines thought?”) I want to erase that complacency, add to reader immersion by showing the world as my characters understood it. If they believed that family members not buried properly might linger and haunt a home or village—I want to make that be so. To give value to the worldview of the past, take my readers further in that way.

The idea of history, of memory, of reaching backward, weaves through this book. We see it in Qi Wai’s collecting and cataloguing of relics, in Lin Shan’s admiration of earlier poets, in Ren Daiyan’s hero-worship of warriors of past dynasties, and even in the way the whole book is told, as you switch between immediate perspectives and a sense of a narrator looking back at the events as they happened long ago. This pairs with the idea that small actions and circumstances may have a larger effect on world events. This sense of remembrance is seen in earlier works, too—I’m thinking specifically about the banishment of the memory of Tigana, and the recurrence and inevitability of the Arthur/Guinevere/Lancelot pattern in Fionavar. Could you talk a bit about the importance of these themes in your work?

That’s a sharp question, and I think I have half-answered it above! In an epigraph to my fourth book, Tigana, I quote the Greek poet George Seferis about how remembering either too much or too little is dangerous, destructive. That’s probably an ongoing motif that runs through my work—it is certainly very strong, as you say, in Under Heaven. I think forgetting the past leaves us rootless, ungrounded, lost. But also that obsessing with the past, being locked into recollections and injustices, or fears, can also cause us to lose ourselves. Certainly the other issue you raise—the interplay of individual initiative and character, as it plays against random events and the “force of history” is another thing I spend time working with. But I worry these answers make the novels sound like dissertations! My underlying goal is to keep you up till 3 AM turning pages. . . then having the books linger (in memory!) for a long time after.

In researching this book I imagine you read many poems and songs in order to write poetry by many different poets in River of Stars. Do you have a favourite Song Dynasty poet now, or any particular ci that have become favourites?

Well, Li Qingzhao herself (there are 2-3 different translations of her work into English) is exquisite and fascinating, as a writer and as a person. But the great, great Song literary figure is Su Shi (sometimes called Su Dongpo, a nickname). He inspired one of the supporting characters in River of Stars and he’s a magnificent historical figure. Poet, politician, diplomat, philosopher, wine-lover, humourist. He’d easily be my favourite. Also widely translated. I like Burton Watson’s versions best, I think.

Might we see more set in the world of Kitai in the future? What other times, spaces, and people intrigue you that you want to write about? That question every author loves at the launch of their latest book: what’s next?

Loves? You think we love. . . ah! You are being ironic. Okay then! The honest truth is that I never know. Not avoiding an answer, just don’t know. Sometime this summer a nagging voice will get really nagging, and I’ll start to become brooding and irritable, and everyone around me will know I am trying to figure out what comes next.

River of Stars: available April 4th at fine independent bookstores everywhere (check Indiebound), as well as Amazon and Indigo.

For more on Guy Gavriel Kay, you can read my recap of his reading and Q&A with Chatelaine books editor Laurie Grassi at the Toronto Reference Library’s Appel Salon.

You might also like:

Wow. Jealous!

One of the first “Post Tolkien” fantasy novels I ever read was the Fionavar Tapestry, and it firmly entrenched my love of Fantasy, so I have very fond memories of reading Guy Gavriel Kay, although I haven’t picked up any of his work in almost two decades.

I may have to change that policy…

Was he a nice guy? Friendly? Obviously very educated…

I didn’t realize you were a Kay fan. I would have done my best to procure an autograph for you. I’ll lend you things, okay?

He’s incredibly intelligent, incredibly erudite, seems like a genuinely good guy.

Reblogged this on halfmidnight and commented:

A broad discussion of Guy Gavriel Kay’s work in an interview with him that also has some fascinating things to say about River of Stars. Also, I clearly need to read Under Heaven.

Thanks for stopping by. I would highly recommend Under Heaven too!

awesome blog, sincerely, from the fantasy writer of LondenBerg by Lord Biron

Thanks very much!