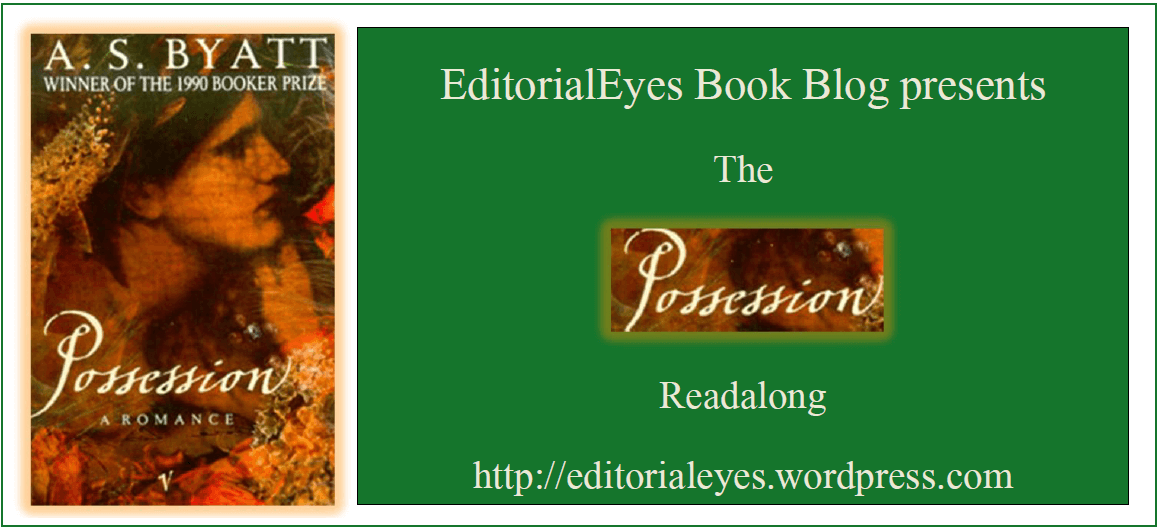

Part 1: Chapters 1, 2, and 3

Part 1: Chapters 1, 2, and 3

Next week, Chapters 4 and 5

The story so far. . .

Chapter One

Possession

opens with a quote from a long poem called “The Garden of Prosperina,” written in in 1861 by one Randolph Henry Ash. Twenty-nine-year-old British scholar Roland Michell is at the London Library. His area of expertise is Randolph Henry Ash, and he works part time as a research for Professor James Blackadder,

a man who has been working on the complete edition of Ash’s poems for his entire academic career. Roland is look for a copy of Vico’s

Principj di Scienza Nuova

—the very copy that Ash once owned himself—hoping to find links in the text of the book that might show influences on Ash’s “The Garden of Proserpina.”

Roland discovers that the book, laced with “a black, thick, tenacious Victorian dust” (p. 2) has been undisturbed possibly since Ash himself last closed the book in the 1800s. This could be a big deal for Ash scholars, since most of Ash’s belongings have been secreted out of the UK and to Robert Dale Owen University in New Mexico under the supervision of an Ash expert named Mortimer Cropper.

Inside the Vico are a number of inserts—book-bills and the like—covered in what Roland immediately recognizes as Ash’s handwriting; they are notes on the text. And, Roland soon finds, there are also two drafts of a letter addressed only to “Madam.” Roland is shocked. As far as anyone is concerned—and Ash scholars know a lot about Ash’s daily life, his comings and goings, his friends and colleagues—Ash was happily married to his wife Ellen for forty years. And yet in these two drafts, he expresses excitement regarding the conversation he and this “Madam” had at a mutual acquaintance’s home, and an urgency that they speak again. Whoever this woman is, she understood Ash’s newest poetry collection (lambasted by critics at the time) and he felt an extraordinary connection with her. The two drafts are full of crossed-out lines as Ash tried to revise his thoughts coherently and tamp down the overly eager excitement shining through.

Roland is shocked. Ash scholars know so much about the poet’s movements, and yet nothing has ever suggested that he was anything but faithful to his wife Ellen or that he had any sort of intellectual liaison with a woman. Surprising himself, Roland tucks the letters into his own briefcase in order to either borrow or steal them from the Library, then finishes his work with the Vico and returns it.

Chapter Two

The chapter begins with a quote from Ash’s epic poem “Ragnarok,” which suggests that a man is composed of many things, his own history, things said to him, his nation, his race. This leads into a brief exploration of the things Roland sees as shaping his character. His mother, disappointed in the road her life had taken, had made sure that Roland had received a comprehensive academic education, which led to his acceptance into university and his eventual PhD. Roland returns home to the basement flat he shares with his girlfriend Val, who personifies the other force he sees as having shaped all his life. He doesn’t believe he’d have finished his First without Val’s encouragement, and her bitterness and mood swings now continue to shape his daily life.

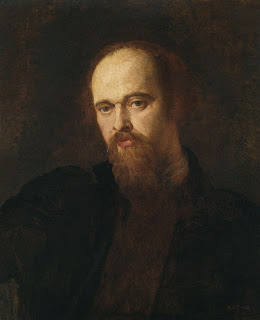

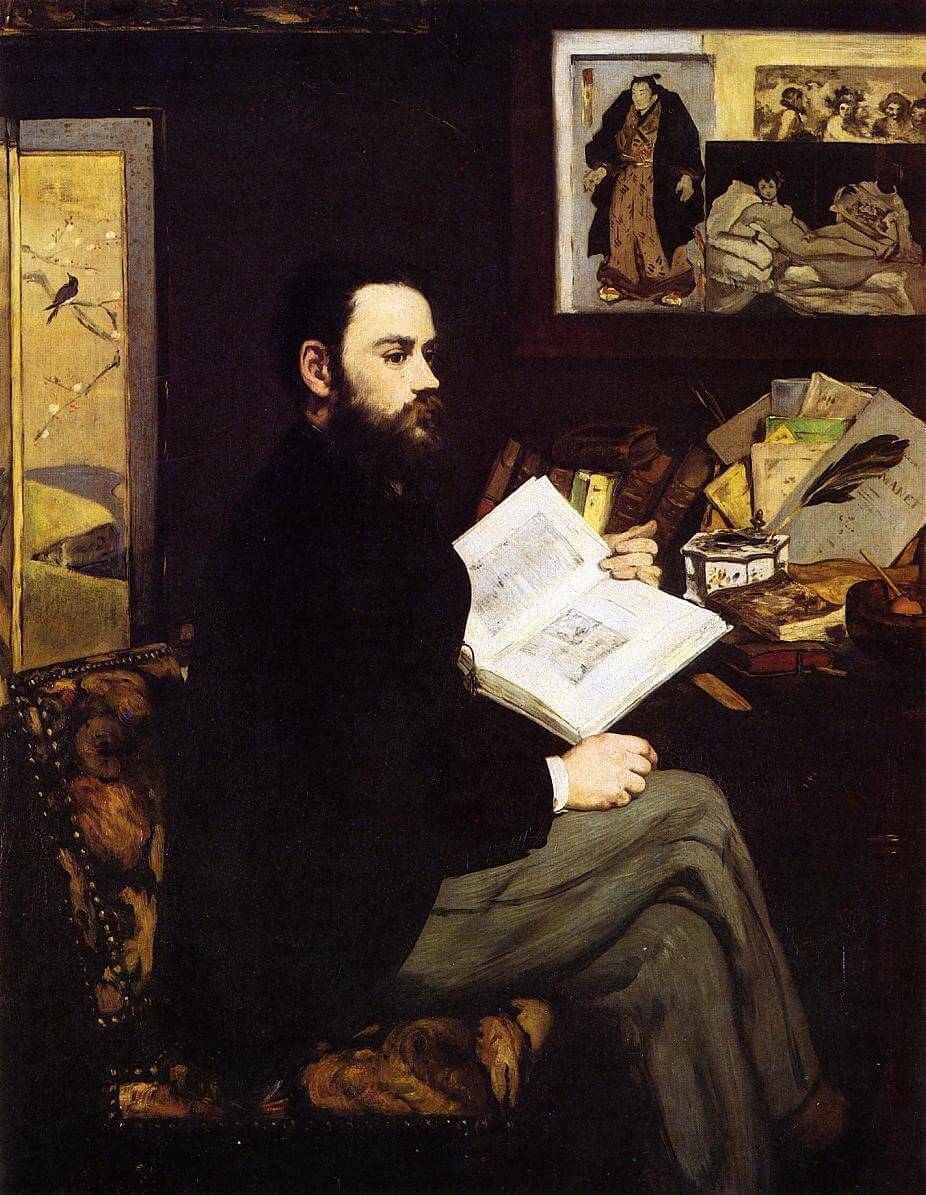

This evening, he can see that she is in a bad mood but isn’t sure what’s set her off. He tries to tell her about his discovery of the letters but she loses her temper with him. She hates their flat (which is so small because Roland can barely contribute to the household income, and which looks out into a garden they aren’t allowed access to; and because, it seems, so much of Roland’s life is dominated by Ash, from his framed copies of portraits of Ash done by G.F. Watts and Édouard Manet to the topics of his conversations and his work). They go to bed, Val angry and Roland vexed, clearly unhappy with the relationship but not strong enough to do anything about it.

Chapter Three

This chapter begins with another quote from Ash’s “Ragnarok III” about “this dim space”: appropriately, Roland returns to what is known as “the Ash factory,” a group of research assistants working under Blackadder in the basement of the British Museum to compile all things Ash. But first he stops at the Dr. Williams Library. He wants to check the diary of Crabb Robinson, the man at whose gathering Ash says he met the unknown “Madam” of his draft letters. Roland knows, based on which of Ash’s works he references as “new,” roughly what year to look for the encounter, as well as who else was at the party. Sure enough, he finds what must be the right gathering, a breakfast party at which a Christabel Lamotte had come out, as a special favour to Crabbe, to discuss her father’s Mythologies. The conversation was animated, touching on the spiritualist movement and on Ash’s own poetry.

Roland copies out the passage in its entirety (by hand, of course, as this is 1986) and muses on the nature of copying: though he is careful, there is no such thing as an error-free text. Texts are almost always accidentally corrupted in some way. He then returns to the Ash factory, akin to “that dim space” referenced in the Ash poem at the start of the chapter. Blackadder’s background is given: in his fifties, he was schooled on Ash, amongst others, by his father and grandfather, then studied under F.R. Leavis and became an expert on Ash. With the blessing of the current Lord Ash, a descendant of one of Ash’s remote cousins, he began work in 1959 on The Complete Poems and Plays, a task which still consumes him and which he has come to terms with as his life’s work: “There were times when Blackadder allowed himself to see clearly that he would end his working life, that is to say his conscious thinking life, in this task, that all his thoughts would have been another man’s thoughts, all his work another man’s work” (p. 29).

Roland seeks Blackadder out, telling the professor, along with Blackadder’s assistant Paola, about the extra notes he found in the Vico. Blackadder is reluctant to show excitement; further, he is concerned that if this truly is an important discovery, his academic rival Cropper, the monied American, will send some cash to the London Library and spirit Ash’s Vico away. This has happened more than once, to Blackadder’s continuing dismay. Roland asks him about Christabel Lamotte. Blackadder refers first to her father, who wrote a compendium of Breton folklore, and then dismissively of Christabel herself, saying she wrote some religious poetry and children’s stories, and one really bad epic, which Paola points out is very fashionable right now with “the feminists.” Blackadder dismisses the feminists too, muttering acerbically about his colleague Beatrice Nest, who has a cubicle in the Ash factory and who has the rights to study all of Ellen Ash’s writings. Ellen, wife of Randolph Henry, is described as terribly dull and upstanding by Blackadder, while, he says, feminists today want a woman who was forced down by her husband, whose thoughts were stolen by him, and so forth. Beatrice’s style of scholarship went out of style in the years she has put into editing the complete Ellen Ash, making her obsolete before she has ever finished her work.

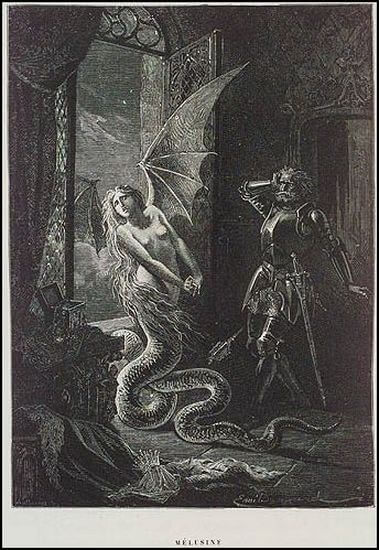

Roland meets up with a colleague, Fergus Wolff, who happens to be the man who beat out Roland for the one available position in the literature department. (Val hates Fergus for it, but Roland rather likes the man in spite of the rivalry.) Roland asks Fergus if he knows anything about Christabel Lamotte. Indeed he does: she wrote an epic poem called “The Fairy Melusina,” a strange piece about a fairy “who married a mortal to gain a soul,” on the condition that he never spy on her on Saturdays. They had several children together, all with strange defects. The husband spies on her through a keyhole, of course, during one of the forbidden Saturdays, and sees that while her top half is that of a human woman, the bottom half is, depending on the version, that of a snake, a fish, or a large andouille sausage. The symbolism, says Fergus, is obvious. He keeps his discovery to himself, but eventually, one of their monstrous children murders another and the husband blames her for it because she is a snake. Enraged that he broke his promise and knows her secret, Melusina turns into a dragon. “She’s a kind of Dame Blanche, or Fata Bianca,” says Fergus. Also, it turns out that Fergus had a brief affair with one of the few Lamotte experts, a woman named Maud Bailey, who, Fergus warns Roland, “thicks men’s blood with cold.”

Some Thoughts. . .

What seems like a quiet start, a discovery in a library, followed by a scene at home and another in a research office, packs a lot of punch. We get a stunningly complete picture of Randolph Henry Ash. The details A.S. Byatt weaves in are remarkable. From descriptions of the two portraits Roland has on his wall, painted by Manet and G.F. Watts, we see first how important a figure in the Victorian era Ash must have been, second what he looks like (“Manet’s Ash was dark, powerful, with deepset eyes under a strong brow, a vigorous beard and a look of confident private amusement” [p. 16]), and third, how varied his interests were. Rocks and geodes are on his desk, indoor gardens grow behind him, he has a skeleton of cat handy and a pile of disparate books.

In contrast to Ash, who is so knowledgeable about so many things, who seems utterly confident in his intellect and curiosities, Roland is difficult to get a read on at first. He is our main character, the point of view we’re given for the majority of this section, and yet he’s not a terribly strong person. He’s a wishy-washy guy; he went to the schools his mother wanted for him, followed the academic course she set out for him. He researches what he is told to research by Blackadder. And what he studies, like Blackadder, is the past, lives already lived. He knows Ash’s personality, and Crabb’s, and many others’, like they were family. He can track their movements through their meticulous diaries. But he doesn’t seem to have that much connection to the living world of the present. He stays with Val out of apathy, or perhaps fear of the unknown, but doesn’t seem to have a great deal of affection for or attraction to her. He doesn’t want to rock the boat by complaining about their living arrangement because she’s the breadwinner. The nickname she calls him, Mole, is one he can’t stand and yet he never tells her he doesn’t like it. It’s an apt nickname, though. At the beginning of this story, he is a small man living in the dark, both physically in his basement flat and at work in the bowels of the British museum, and mentally, in the recesses of other people’s minds.

An obsession with death and the dead exists in characters like Roland and Blackadder, so concerned with exactly what these dead Victorians thought and felt and wrote and meant. Far more emphasis is placed on this scholarship than on the real world, or at least on the world outside of academia. It’s not clear to those of us outside Ash scholarship why these letters are so important, for example, what this one particular Victorian poet was actually thinking when he met this unknown woman.

Ash’s writings are also presented in snippets, and he is referred to by several different scholars as a ventriloquist, someone capable of writing Norse epics, love sonnets, Jacobean dramatic verse. His copy of “the New Science” is heavily annotated. This is clearly a man of prodigious intellect; it’s particularly interesting that this man who could take on so many voices clearly had difficulty getting his own voice under control as he tried with evident difficulty to write to Christabel. Further, seeing the crossed-out parts of his drafts offers insight into what he wanted to say but thought better of. The strikethrough is a powerful storytelling device, showing us Ash’s true thoughts while also telling us that he took them back, revised them, offered up a different sentence or sentiment in their place.

And we also see the world of the modern (in the book’s day, more on that in a moment) scholars whose own lives are subsumed by the dead people they study. Beatrice Nest has worked for so many years without publishing anything on Ellen Ash that she has rendered herself obsolete. Scholarship, always terribly given to trends and trendiness, has moved on. But Beatrice has the rights to work on Ellen’s things. She possesses Ellen and the Ellen scholarship in a way that the younger generation of feminist researchers do not.

This idea of possession in terms of intellectual pursuits and the actual artifacts of the dead begins early, and is something we’ll see throughout the book. We’ve yet to meet Mortimer Cropper but he’s referred to several times. His actual physical possession of so many of Ash’s things, from furniture to notes to books to manuscripts, irritates Blackadder, who thinks the British should own these things and study them because Ash was British. Blackadder considers the difference in the way he and Cropper approach Ash: “he believed Mortimer Cropper thought himself the lord and owner of Ash, but he, Blackadder, knew his place better” (p. 29). Roland, too, muses on the idea of ownership, which also plays heavily on the concept of authenticity. Roland also dismisses the way Cropper behaves about Ash, pulling out Ash’s own pocketwatch, sitting where Ash sat. Roland isn’t interested in these things. And yet, Roland does steal the letters; he hardly understands why himself, or why he doesn’t share the discovery with Blackadder or any of the others. He makes photocopies, which he acknowledges are actually easier to read than the originals, but he still wants to possess the originals. He goes so far as to make up a story about the papers flying everywhere when he opened the book, ostensibly to cover up anything that might be found missing from inside the Vico.

Why is it better to possess the actual letter, more than the more legible copy? What is the point of authenticity? What does it bring with it, what does it mean? Roland doesn’t want artifacts generally but he does “take pleasure” in letting his eyes read the very words that Ash would have read in Ash’s own copy of Vico. The London Library owns this book once owned by the poet, and Cropper will likely want to take it for himself. Roland only wants the letters, and he wants to find out more about the mysterious Christabel Lamotte, who so far we have only seen through the eyes of others. She, like her modern counterpart Maud, exist only in the stories told by someone else and not, as Ash does, clearly in the mind of the reader. At least not yet.

Val, the other major character introduced to us, is also a difficult one. Self-involved and self-pitying, defining herself by how much she has been defined by Roland, she’s something of an anti-feminist or a crypto-heteronormativist. Sure, she’s the breadwinner, but she based her academic career on what Roland was studying, blamed him when it went south, and left academia entirely. She seems now to hate all things Ash, forcing Roland to keep his Ash things out of her line of sight, not wanting to hear about what he’s studying. We only see her through Roland’s eyes, to be sure, and he doesn’t have a terribly high opinion of her at the moment, but her emphasis on how menial her job is and therefore how menial her life is, her constant repetition of the word “menial,” gives a good idea of what she’s like.

She does provide an important clue to where the book is headed when Roland observes that there are actually two Vals: “one sat silently at home in old jeans and…lustreless brown hair…Just sometimes this one had crimson nails left over from the other, who wore a tight black skirt and a black jacket with padded shoulders over a pink silk shirt and was carefully made up with pink and brown eye shadow, brushed blusher along the cheekbone and plummy lips. This mournfully bright menial Val wore high heels and a black beret” (p. 14). Defined by the difference in dress, we see what Roland means: the work-Val who is sad but made up, and the equally sad home-Val, who is a bit of a mess and likely who would not be recognized at first by people who only know work-Val. She has two totally different selves. Soon, we will see that Randolph Henry Ash is just the same. None of these bright minds who obsess over Ash know what Roland is about to discover regarding Ash’s private life.

Finally, a note about the “modern” scholarship: it’s fascinating to me how much things have changed in such little time. The fact that Roland has his boxes of index cards, which he dutifully uses to cross-reference facts, is astounding to me. The painstaking handwritten notes, the knowledge that this transcription will cause the text to be corrupted in some way, the use of typewriters, and the complete and total lack of computers and the internet add a layer to this story not originally intended by Byatt. This is simply not how modern research works, at least in its trappings. It makes me wonder what would happen if the Ash discovery happened now. Would a quick look at Google Maps have made life easier for the search to come? In fact, as I was putting the visuals together for this post, I was frustrated because I had found the woodcut image of Melusine above but the site I’d found it on gave no credit or reference for it. Who had made this art? And when? So, what rigorous research did I do? I saved the image, dragged it from its folder into Google Image Search, and Google found the information for me. It didn’t take more than ten seconds from wondering who the artist was to finding him. Google pulled up the image in other sources, suggested (correctly) who it thought had made the art, and gave me a variety of links to sources about the artist. How much scholarship has changed!

What do you think of the story so far? Next week, we’ll meet the female protagonists of our tale, Maud and Christabel, and learn more about the mysterious letters. . . stay tuned!

You might also like: