Introduction

Part 1: The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing (first half)

Part 2: Letters from Zedelghem (first half)

Part 3: Half-Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery (first half)

Part 4: The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish (first half)

Part 5: An Orison of Sonmi~451 (first half)

Part 6: Sloosha’s Crossin’ an’ Ev’rythin’ After

The Story So Far . . .

Sloosha’s Crossin’ really is a crossing, the point at which we move out of the first halves of the six narratives and cross over to the second halves. Sloosha’s is presented in its entirety, in the first person, as an older Zachry tells the tale of his life, presumably to a group of children gathered ’round. The first thing you’ll notice is the dialect: it’s written in English, but a corrupted (or evolved) form of English that is as foreign to modern ears as Adam Ewing’s 19th-century English is.

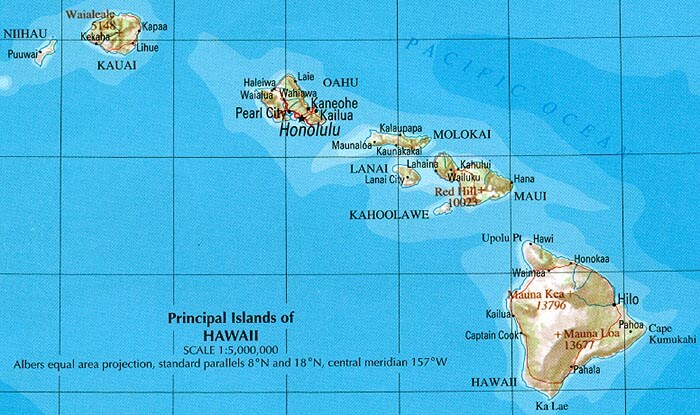

Zachry’s tale begins on Big I, in the Hawaiian islands, long after The Fall of humankind. When he is 9 years old, he, his brother Adam, and their pa are on their way back from Honokaa Market, when Zachry goes into the bush after a bird. He hears the voice of Old Georgie (the Devil) whispering to him, and becomes aware that Kona raiders are about. He accidentally leads the Kona back to where his family is, and then hides while the Kona butcher his father and take his brother as a slave. Horrified, he returns to the Valley where he lives, reporting the Kona attack but never telling anyone that he led the warriors to Sloosha’s Crossin’.

Zachry talks about his gift for herding goats, and the peaceful lives of the Valleysman. Because of his goats, he knows the Kohala Mountains well and knows of the existence of a few Old Un buildings there that others are unaware of. He recounts the tale of his first baby, when he and a girl named Jayjo are 12 years old. Assuming they will settle down together, everyone is saddened when the baby boy is born without a mouth or nose holes, and suffocates immediately after being born.

Back in the “present” of the yarnin’, Zachry digresses somewhat. He discusses the one true god followed by the Valleysmen, Sonmi, who lives amongst her followers, saves the sick, and guides souls from the bodies they died in to the wombs where they will be reborn. The only obstacle to this process is bad deeds, which Old Georgie stones a soul for, eventually claiming a heavily stoned soul for his own and eating it. That soul will never be reborn after that. Zachry figures his soul is already partly stoned because of the events at Sloosha’s Crossin’.

But the Valleysmen believe inherently in rebirths. He mentions the School’ry as one of the special places that housed Old-Un Smart, including windows made of glass, books, and “the greatest of ‘mazements,” the only still-working clock on all of Ha-Why: “I mem’ry Abbess sayin’, Civ’lize needs time, an’ if we let this clock die, time’ll die too, an’ then how can we bring back the Civ’lize Days as it was b’fore the Fall?” (p. 247).

The Valleysmen also have an Icon’ry, where the icons of each person are kept. Valleysmen carve their own icons in life as a sort of living record to be left behind and to be shown respect after their deaths. Zachry has been in the Icon’ry twice at this point, once to pray to Sonmi for his mother’s health, and once during his Dreaming Night, when he was 14 years old and therefore a man. On this vision quest, Zachry dreamed, and the Abbess augered his dreams:

“One: Hands are burnin’, let that rope be not cut.

Two: Enemy’s sleepin’, let his throat be not slit.

Three: Bronze is burnin’, let that bridge be not crossed.” (p. 247)

The storytelling Zachry is drawn by his invisible audience to tell the tale of the Ship of the Prescients, whose magical ships glided across the water to trade once a year with the Valleysmen. The Prescients have more of the Smart of the Old Uns and would barter incredible ironware for foodstuffs, never giving Smart greater than what was already available on Big I, nor talking about what the rest of the “hole world” is like, preserving the Valleysmen’s level of Smart and Civ’lize and never disabusing them of any notions they might have.

One particular year, Zachry is tending to his goats, and to a girl named Roses, when the Prescients arrive for their annual bartering. He doesn’t bother going to see them, assuming his mother will. She, however, wasn’t able to get there either, and to their surprise, they discover that one of the Prescients, a Shipwoman named Meronym, has asked to live among the Valleysmen for six moons. In return for the Valleysmen’s generosity, the Prescients have given twice as many bartered goods as usual. And because no one was there to represent Zachry’s household, and because everyone is skittish about having a stranger from a strange tribe living with them, the group voted Zachry’s dwelling to be the one to host Meronym.

Meronym arrives with gifts for each member of Zachry’s household, but he is suspicious of her motives and refuses her gifts. He dislikes the way others from the village ask her questions and pretend to understand her answers. He thinks she tells many lies, but acknowledges that a few things she says may be truths: that her ancestors darkened the colour of their skin in order to cope with “the red-scab sickness,” and that she is fifty years old, which shocks the Valleysmen, who rarely live past forty. Zachry feels she is unnatural, and dislikes the way she settles in amongst them, learning their ways.

One day she accompanies him goatherding and he sees her drawing a map of the terrain. He goes to the abbess with his concerns that she plans to harm the Valleysmen, but the Abbess tells him he must have evidence to support such a huge accusation. As Meronym’s popularity grows, so do Zachry’s suspicions. When he hears her asking questions about the Icon’ry, he lies in wait there, expecting her to sneak in and do harm to their most sacred space, Sonmi’s dwelling. Instead, he finds one of his own people, Napes, guiding her in and telling her about the time his ancestor went all the way to the top of Mauna Kea, shared loot with a ghost, and met Old Georgie himself. Georgie laid claim to Napes’ ancestor’s soul, for the top of Mauna Kea is Georgie’s dwelling. Napes leaves to give Meronym time to explore, and Meronym addresses Zachry: somehow, she has known he was there the whole time. Zachry accuses her of not telling him the whole truth about her purposes there. She, in turns, points out that she knows he has a secret too, and his mind flies to thoughts of Sloosha’s Crossin’, which no one knows about. She swears to him that the Prescients mean the Valleysmen no harm, but he doesn’t believe her.

Instead, Zachry waits until she’s out and goes rooting through her things. He finds a silvery egg, which when warmed to the touch produces the image of a ghost girl. She seems to be answering questions in Old-Un tongue, and he is haunted by her. Suddenly her image disappears and is replaced by a man who is addressing Zachry, scolding him for going through his guest’s things.

Three moons later, Zachry’s little sister Catkin steps on a scorpion fish and falls deathly ill. Zachry begs Meronym to use her Smart to save Catkin. Meronym refuses, saying she can’t get involved in Valleysmen’s destinies. Zachry throws himself upon her mercy, admitting to everything that happened at Sloosha’s Crossin’, giving her that bargaining chip over him in exchange for her help. Reluctantly, she gives him a pill and makes him swear that he will administer it without anyone seeing, and if Catkin survives, he’s to give all credit to the village herbalist.

Later on, after Catkin recovers, Meronym reveals a desire to climb Mauna Kea. Zachry volunteers to go with her: “One, I owed Meronym for Catkin. Two, my soul was ‘ready half stoned, yay, surefire I’d not get rebirthed, so what’d I got to lose? Better if Old Georgie ate my soul ‘n someun else’s who’d get rebirthed else, yay? That ain’t brave, nay, it’s jus’ sense” (p 269). They set out together, passing by Sloosha’s Crossin’ and at one point hiding from Kona raiders. They trade stories, and after Zachry asks her several questions, Meronym tells him some truths he has trouble believing: that the Fall wiped out almost the whole world, with only tiny pockets of Civ’lize left, that the Fall was not “tripped” by Old Georgie but by Old Uns themselves because of their awful hunger for more of everything, and that his god, Sonmi, was a “freakbirthed” human who lived and died hundreds of years ago, and isn’t a deity.

One night when they make camp, Meronym falls asleep but Zachry sees a Honomu fisher appear, wanting to share their fire. He knows this is a ghost, like the one that Napes’ ancestor saw. The next day, Meronym gives Zachry a pair of Prescient boots because his footwear has worn through. They reach the gates to the Old Un settlement and use a rope to climb over them. Inside are buildings that Meronym calls “observ’trees,” where Old-Un priests studied the moon and stars.

Meronym removes the silvery egg, which she calls an orison, and uses its Smart to record everything she can. As she works, Zachry is plagued by visions and voices sent by Old Georgie. This is his dwelling, and he urges Zachry to murder Meronym for the good of the Valleysmen. Not knowing his internal struggle but sensing that he is troubled, Meronym tells Zachry that the thin air can play tricks on them.

In one building, they come across the well-preserved body of what Meronym calls a “chief ‘stronomer” and Zachry believes is a “soocided priest-king.” The dead man speaks to Zachry, urging him to murder Meronym because she is sick with Smart the way the Old Uns were. Zachry finally agrees to murder her, and when they step outside, he raises his spiker…

This, I think, would be the place where the story would break, if there were yet another narrative after it. However, this is the central tale, and so it continues. In a split second, Sonmi changes Zachry’s mind and he throws his spiker high over Meronym’s head. She never knows he nearly killed her. Still, Old Georgie is after him, and as they climb the rope over the gate, he urges Zachry to cut the rope. But Zachry remembers the Abbess’s auguring and refuses: “let that rope be not cut.” Georgie threatens to kill all of Zachry’s family in revenge.

Back down to the village they go, closer and more understanding of each other now. Zachry finds he has some notoriety, and mothers are telling their daughters to stay away from him for he must have sold his soul to Old Georgie while he was on Mauna Kea.

Meronym’s last moon with the Valleysmen coincides with the yearly Honokaa Market. She accompanies the Valleysmen, who are laden down with the extra Prescient goods for barter, as Zachry’s “Aunt Ottery,” who does drawings of people at the market, much to everyone’s astonishment. The market is a time of celebration and trade, when all the peaceful tribes come together, share their food and drink and weed in a show of generosity that resembles the Haida potlatch, and celebrate together.

Zachry spends that night with a Kolekole girl in her camp, but in the morning he dreams that his long-dead father is urging him to wake up. As he goes to find breakfast, he realizes that the sounds he thought were carried-over partying are actually battle. The Kona have amassed their forces and have attacked all of the tribes at this time of peace and trust. They are enslaving, raping, and/or killing everyone in their wake.

Zachry is captured and despairs for his family and the bleak outlook for his enslaved future. He realizes that one of the men he spoke with the day before, Lyons, has betrayed them all. Then one of the slave boys is selected and gangraped by the Kona. Just as Lyons is about to have his turn, another Kona appears on the scene and uses an incomprehensible weapon to quickly and quietly kill all of the Kona. This, of course, is really Meronym in disguise.

Meronym and Zachry consult the orison. Duophysite, the man who earlier scolded Zachry, now asks for his help in getting Meronym to Ikat’s Finger, where Prescient kayaks will be waiting for her. It seems that the whole of Big I has been enslaved by the Kona, and more troubling to the Prescients, a plague has been moving through other pockets of people and seems to have wiped out the Prescients on the Ship. In return for Zachry’s help, there is a place for him on the kayaks. Zachry agrees to get Meronym there but will stay on the island to look for his kin. Meronym admits that Zachry’s suspicions of her actually had a shade of truth to them: the Prescients have been seeking a new place to settle because of this plague.

Together, Meronym and Zachry double back to the village. Heads are on pikes and no one seems to have survived or escaped enslavement. Zachry laments the burned-out school’ry. The last of the Old Un books are gone, and the last clock is gone. Kona guard the village, but Zachry and Meronym sneak into his old home, where it is clear his mother and sisters have been killed or taken. Sorrowfully they leave, but Zachry insists on stopping at the Icon’ry first, to save his kin’s Icons if nothing else. There, he finds a sleeping Kona. He grapples with himself, remember the second auguring: “Enemy’s sleeping, let his throat be not slit.” Though he wrestles with himself and knows it is “right” to leave the Kona be, he exacts revenge anyway and slits his throat. He grabs the Icons and they hightail it out of there, but soon after they leave the alarm is raised: the dead Kona has been found, and Zachry’s actions have made escape that much more difficult.

But luck is with them, and as they make their way to Ikat’s Finger, Zachry wonders how and where the souls of Valleysmen will be reborn without Valleyswomen’s wombs to be reborn in. He asks Meronym if Civ’lized or savage people are the stronger, and Meronym tells him they approach the world differently: savage people take whatever they want right away with no thought of the future, Civ’lized people plan ahead and go without in the present if it means a better future. She tells him that the Old Uns had some of both in them.

Nearly to Ikat’s Finger, they come across a whole platoon of Kona. Meronym is able to bluff them a little, making them think she is a Kona general long enough to gain a head start, but the Kona attack, shooting a crossbow bolt into Zachry’s calf. They gallop toward the bridge over the Pololu River, and Zachry remembers the third auguring, “Bronze is burnin’ let that bridge be not crossed.” He convinces Meronym to forgo the bridge ride their horses through the river instead, and sure enough as the heavily armoured Kona thunder across, the bridge gives way and they plunge to their deaths. This gives Meronym and Zachry enough time to get to the meeting spot for the kayaks. Meronym does her best to heal Zachry’s calf and gives him something for the pain. In a haze, he misses the Prescients’ arrival, and when he awakens he is on the kayaks: Meronym has made the decision that she cannot leave him behind to an almost certainly dire fate.

Zachry the storyteller in the present winds down his yarn, and the narrator’s voice then changes to that of Zachry’s grown son, who is either interjecting or has, perhaps, been retelling his father’s telling. This new narrator informs us that Zachry’s yarns were often just “musey duck fartin'” (p. 308), stories for children and stories that have grown a bit crazy in his old age. Zachry even believed that Meronym was the reincarnation of Sonmi because of her comet-shaped birthmark. Zachry’s son believes there is a lot of truth to the yarns about Meronym and the escape from the Kona, and indeed he still has the silvery egg in his posession. He gives the egg to his audience, and bids us to hold it and look at what the egg will show.

Some Thoughts…

Seriously, doesn’t that give you goosebumps? Sloosha’s sets up the boomerang back into the latter halves of the first five stories by actually handing we readers/listeners the orison and asking us to look at it.

In many ways, this most complex of all the narrative voices is telling the most straightforward adventure story. In several places, Zachry and then his son make clear that his yarnin’s are not necessarily 100 percent true. His talks with Old Georgie strike me as embellishments meant to scare children around the campfire rather than the “hole true” of what actually happened to him. Meronym’s recounting of the Prometheus-inspired story about how the survivors of the Fall in Panama were given fire by Crow, who flew to the Mighty Volcano and fetched fire for the people, hints at this: stories are stories that have within them kernels of truth but are not always a blow-by-blow factual account. This doesn’t make their meanings or emotional resonances any less true or necessary. What of Zachry’s yarnin’ is true and what is false or embellishment? I think the meat of the story truly happened, but his hallucinations of ghosts and maybe even the augurings are later additions for the benefit of his audience.

In this section we see the culmination of hints of disaster that have played out earlier. There is mention of the great city of “Buenas Yerbs” that was wiped out in the Fall, which hearkens back to the setting of Luisa Rey’s story, and there is a tribe of “Swanekke,” who must be the survivors in that area. We have the “red-scab” disease that is alluded to in Sonmi~451’s story, and references to how much of the world is “deadlanded,” which again speaks to the idea of nuclear disaster wiping most of humanity out. Sonmi herself has gone from a clone about to be executed, as we last saw her, to a deity: somehow, her story, her words, have become teachings that have spread through the last pockets of Civ’lize. Zachry has trouble believing she was a (freakbirthed) human who lived and died, and isn’t a god.

The transient nature of religions is suggested here. While Sonmi is the absolute god of the Valleysmen, Zachry refers to a strange Old-Un building called “Church” where part of the Honokaa Market takes place: “Last there was the bart’rin’ hall, a whoah spacy buildin’ what Abbess said was once named church where an ancient god was worshiped, but the knowin’ of that god was lost in the Fall” (p. 285). Further, the Prescient Duophysite’s name raises some questions: it is close to “dyophysite,” a word used in Christian theology that refers to the dual nature of human and divine in Jesus Christ. Does this speak to the higher level of Smart the Prescients have, the closer to “godliness” they are, or the dual nature that Meronym refers to in the Old Uns to be both Civ’lize and savage? The Prescients, one would assume, have some psychic ability, based on what they call themselves, and on how Meronym seems to know where Zachry is and at least the basics of his mood even when he isn’t volunteering that information. Or perhaps they call themselves Presicents because they are able to learn from the past to see into the future, to understand that humanity has to be kept from hungering too much if it is to survive itself.

Other points of connection to past stories are subtle, for example Zachry learning to shoot by aiming for ever smaller pieces of fruit, which recalls the abusive situation Chang pulls Sonmi out of when Boom-Sook and his drunken friends try to shoot ever small pieces of fruit off her head. And of course the comet-shaped birthmark, which appears in this story on Meronym’s shoulder. Somehow, Zachry is able to piece this together with information about Sonmi, or so it would seem from his son’s thoughts on his father’s “loonsome” ideas.

We have the very physical theme of ascent here as Zachry and Meronym ascend Mauna Kea, which recalls Adam Ewing’s ascent up the Conical Tor in the first story. The metaphorical ascent/descent theme is at play here as well: as they reach the top and see all that the Old Uns had once had to offer, Zachry wrestles with the idea of murder. And not long after their descent, the Kona attack, plunging the island into war and barbarism. The further descent into Zachry’s home valley shows how much death and destruction has been wrought, and the loss of the Civ’lize, possibly for good (though of course, that Zachry is telling these stories to another generation suggests that human life does continue on, as do societies). This also sets off the “descent” theme in the second halves of the stories, as we will come to see as we descend out of the book.

The idea of the remaining Civ’lize on both Prescient Isle and Ha-Why being wiped out at the same time is interesting, as is the implicit comparison between the plague that kills the Prescients and the Kona who kill the Valleysmen. The ideas of levels of predacity are strongly at work here: the broken state of humanity is the result of the nation-led predacity we’ve seen hinted at in previous narratives. The Kona prey on the other tribes both at the individual level and at the societal level. The slavery we see recalls strongly the tales Mr. D’arnoq tells of the enslavement of the Moriori by the Maori in Adam Ewing’s narrative. But we also have smaller levels of predator/prey happening, for example the villagers all but forcing Zachry’s family to take on Meronym when no one else wanted her, because they weren’t there to speak for themselves, as well as Lyons’ betrayal of the tribes at Honokaa Market.

The idea of Civ’lize needing the time of clock is also playful and intriguing. Without a timepiece, is there time? Does one really need to know the time to be “civlized”? This brings up more questions about the ideas of “truth” and “hole true,” which come up all throughout this narrative. We’ve seen evidence of unreliable narrators in each of our six stories so far. Each, with the possible exception of Luisa Rey’s (but more on that in the upcoming Luisa Rey post) are someone’s tale, someone’s unconscious or deliberate shadings of the truth. Is there ever any real “hole true”? “Then the true true is is diff’rent to the seemin’ true?” Zachry asks Meronym regarding the movement of the earth around the moon (p. 274). Meronym responds, “Yay, an i’t usually is, an’ that’s why true true is presher’n’rarer’n diamonds.” Even as Meronym is totally certain about Prescients’ views of who Sonmi was and the lack of afterlife, Zachry dismisses what she knows as less than what the Valleysmen know: she doesn’t believe in reincarnation, and yet reincarnation exists absolutely for Zachry (and, perhaps, for us as readers, because we have been shown these tantalizing hints all throughout the narratives).

I find with this story that while it’s at first difficult to get into because of the warped and devolved way of speaking, the longer I read it, the easier it is to understand, until at last my brain is reading it rhythmically and without difficulty. This is, to me, as brilliant as any languages Tolkien invented. This is an entirely plausible way for English to morph and change many hundreds or thousands of years down the road, or at least is representative of that change, even as it recalls the difficulties we first have reading Adam’s dialect in the 1850s.

This story also most directly lays out the idea of souls presented in this book, and I’ll leave you with the quote that, to me, most embodies the spirit of Cloud Atlas:

I watched clouds awobbly from the floor o’ that kayak. Souls cross ages like clouds cross skies, an’ tho’ a cloud’s shape nor hue nor size don’t stay the same, it’s still a cloud an’ so is a soul. Who can say where the cloud’s blowed from or who the soul’ll be ‘morrow? Only Sonmi the east an’ the west an’ the compass an’ the atlas, yay, only the atlas o’ clouds.

(p. 308)

You might also like:

|

|

I’m on my second reading of ‘Could Atlas’ and have really enjoyed picking up on connections and referenced in the first part of the book to subsequent chapters, as well as references in the second half to previous chapters that I missed the first go-round. One thing I am not clear on, and I’m hoping someone can explain: At the beginning Sloosha’s Crossin’, Zachary notes that he is a niner when he leads the Kona to his camp where they kill his father and take his brother Adam. Then later, he tells of his first trip to the Icon’ry to ray to Sonmi to heal his mother after Catkin was born. He says he was seven at the time, and he worries about visting the holy site since Georgie had already stoned his soul at Sloosha’s Crossin’. I’m having a hard time reconciling the timeline – does anyone have an explanation?

I’d have to read the pertinent passages again, but it can be explained either as something Mitchell overlooked or Zachry’s own unreliable narration. Are you sure it wasn’t Catkin who was seven at the time?

Yeah, page 245: “First time I went inside the Icon’ry was with Pa’n’Adam’n’Jonas when I was a sevener. Ma’d got a leakin’ malady birthin’ Catkin.” His pa took him to the Icon’ry to pray to Sonmi to heal his mother, and Zachary states, “an’ in my head I prayed the same, tho’ I knowed I been marked by Old Georgie at Sloosha’s Crossin’.”

Hmm His pa and Adam are still alive, too. So, unreliable narration, says I. Mitchell plays with that a lot throughout the book.

Just a note about the Audible version. All of the narrators were excellent, but the one who read Sloosha’s Crossin’ was sensational. He managed to get a real lilt in the narrative, a music, that made simply the sound enchanting. He also made the futuristic English easy to understand. I can imagine the difficulty a reader of hard copy might have encountere.d

Thank you so much for writing this up.. I had the most difficult time understanding ch.6 but now things are crystal clear.

I really struggled with this section. Mostly because of the language. I found it really difficult to read/interpret and therefore hard to get into and enjoy. Ultimately I’m glad I stuck with it because it offered some really interesting insight into the nature of novel/all the characters and I liked how Mitchell seemed to tie in elements from the other 5 stories.

All that being said though, I’m excited I’ve pushed through it so I can see how all the other stories conclude!

Has anyone else picked up on the potential cyclical nature of the story up to this point? Consider this: The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing covers a sea voyage from the perspective of the voyager, stopping at various islands and dealing with natives before heading home. Sloosha’s Crossing is a narrative from the perspective of natives being visited by passing see voyagers. Clearly the author intended to connect the future with the past in this way.

It is, however, and reversed connection, with definite contrasts. In the Journal, the voyager’s lives are disrupted by the presence of a stowaway native. In Sloosha’s, the native’s lives are interrupted by a single sea voyager. In the Journal, the dark-skinned natives are deemed savages, while in Sloosha’s the darker skin of the Precients are a sign of sophistication. Even the children of the Valleymen try to paint their faces black to emulate Meronym’s appearance, only to be chastised and told that the color of one’s skin does not make one important. I wonder what point the author is trying to make by making the Precients more benevolent and egalitarian than the “white man” crew of Ewing’s voyage.

I didn’t read down to Brett’s mention of the “Adam Ewing analogue.” Oops. Still, this is one of the primary connections I came away with.

Absolutely, and thanks for your comment! This is a book about cycles and cyclical nature. We see several major relationships and situations from both sides in different stories. One of my favourites is still the Autua/Adam moment of *seeing* and connection and the Hae-Joo/Sonmi moment of the same. We absolutely see as we go back through to Adam’s story again the many ways his and Zachry’s worlds and narratives are similar. As we’ll see in Sachs’ ponderings about the nature of time in part 9, we’re perhaps looking at an infinite Matryoshka doll set.

Books being turned into movies are always a tough transition. So much is lost, but other things are gained too. The relationship of the Prescients weren’t explained well in the movie. They just sort of come out of nowhere. As someone who didn’t read the book (but I plan to certainly), I was like, “After all the trouble humanity has had up until this point, now these primitive people are being attacked by aliens?!?!” At least that what it seemed like. Then you realized they’re humans, but then you wonder if they don’t have some prime directive about interfering with primitive cultures. Then you get that they’re friends, but then you realize they are talking the same language then it’s like TIME OUT…how is that possible?

Those that have the advanced technology would have had access to all the information from centuries past. I can believe the primitive people might have been talking in some weird devolved dialect, but the Prescients should have still been speaking in a regular English tongue or at least some primary language, maybe only using the devolved dialect to speak with Zachry’s people.

There was a lot the movie glossed over from the book. In some ways good, in some ways bad. After almost 2 hours they were simply running out of time to tell this section better. The relationships were confusing and there wasn’t time to get into any rhythm the language was taking. I have no doubt it’s something someone can get used to but listening to it for a first time it throws you for a look, and certainly doesn’t sound advanced by any means. I have friends from the south who talk like that now!! =P

I maintain that to bring this book to the screen properly, it should be done as a high-budget miniseries, not a movie. There’s just too much good stuff going on in the book that must necessarily be axed from a film to keep to a halfway-decent running time.

You get a much better sense of who the Prescients are and what they’re up to in the book. Their thrust of Meronym’s mission has been changed in the movie (and, in fact, Zachry’s character has also been altered substantially from a boy who isn’t quite a man yet to Tom Hanks…). We know that the Prescients have access to some serious technology but they’ve also lost a lot, too. They have some records, for example, from Sonmi’s time (and the language in Sonmi’s world is already evolving from our own form of English), so it’s not surprising in the book that their language would be similar.

Another thought that’s just occurred to me…perhaps Zachry IS speaking in the dialect of the Prescients. He’s telling the story to an unidentified group of children years after the events he’s relating. He would be telling them the entire story, including any dialogue, in a language they would understand.

Another thought, maybe two, not mutually exclusive:

1) Meronym is speaking to the Valleysmen in their native language, much as visitors to a foreign country speak the local language.

2) Zachry is yarnin’, so he’ll be usin’ language his audience can understand, regardless of which character is speaking.

(First time commenting, I love this read-along. I’ve seen the film and am not quite through the second half of Half-Lives in the book. It’s interesting to see the differences between the book and movie; not just the structure, but plot points as well. Dee, you and my fellow commenters have great insights. Thank you.

Hi! I am very happy I found this website! I absolutely love this book! It is difficult read but this website does help to clarify and understand some ideas. Today I will start reading second part for Cavendish story. The end for sonmi story was shocking to me, especially knowing that everything was staged and she manipulated…

Thanks for reading and commenting! I’m glad you love this book 🙂 I had actually forgotten that that was the outcome of Sonmi’s tale when I started reading this book this time around. I remembered the litehouse, but not the political machinations going on. Sonmi’s is my favourite section, and the ending is so gut-wrenching.

Just wanted to drop a note that I really enjoyed this. I just finished this chapter and am feeling a little melancholic about starting my own “descent” into the second half of the book.

Thanks for reading and commenting! Glad you’re enjoying it. I know what you mean: the first time I read this book, I remember a combination of excitement that I would find out what happens next with all of these stories and wistfulness that we were now leaving these characters.

Hello everyone!

First of all, I love this readalong and I am happy to see that I am not the only one obsessing about this book 🙂

Though I enjoyed reading some of the other stories more, my mind goes back to this one the most. Especially Old Georgie. Is he just living in Zachry’s imagination or is he real? And whom could he resemble from the other stories? It has already been mentioned that Zachry has polished his tale in order to deal with his own temptations and fears. Old Gerogie seems like a methaphor for the devil (or thoughts that are not in line with the ethic codes of his society) on one hand, on the other hand the valleymens’ god Sonmi is a real person. Similar to Buddha, Jesus or Mohammed having most certainly lived some years ago and still being worshipped today. The valleymen are spiritual people and they might have developed special senses for the metaphysic. His tribe could have developed new senses, maybe even triggered by mutiations from the “Fall”. Zachry talks to a ghost at the campfire on the mountain, so his truth of interacting with spirits could be a general truth. I think Meronym mentions earlier that the truth often cannot be understood by the senses, this could be real for her as well especially since the soul (and reincarnations) are an essential part of this book. Happy to read your thoughts as well….

Thanks, Albert. I’m happy you’re here! I agree with you that Old Georgie is the Valleysmen’s version of the Devil, a way to enforce the ethical code and point to punishment for bad behaviour. I hadn’t thought about him as an analogue to Sonmi, perhaps starting out as someone real, but I’ve often wondered where the name “Georgie” came from. Perhaps he is modelled after someone, after all. Interesting….

I read the visions of Georgie and other ghosts as more of old Zachry’s storytelling device than as something that “actually” happened, but as we see all throughout this book, there’s no way of telling what is truth and what is personal reflection or bias. Am I looking through my dispassionate liberal arts 21st century lens and assuming that of course the spirits can’t be real, when in fact they are for Zachry and his people?

You beat me to it. In hindsight, the tale really reads as something he’s polished over his decades of life, telling it over and over again (just like how Luisa Rey thinks that she’s polished the story about How Her Dad Became A Famous Journalist through repeat tellings). It’s interesting that we never find out what happened to Meronym after she helps to heal his leg, which suggests that he either never saw her again, or her fate is one of those things where it’s supposed to be so well-known to the characters (but not to us) that they never bother bringing it up.

It could also be that, since the story is from Zach’ry’s point-of-view, he remembers Meronym as being more wise and understanding than she actually was many years earlier.

To me, the “Prescient” label could refer to two things. The first is what you said, that they’re able to see into the past to see into the future (which fits with the Orisons, including a precious one of Sonmi herself). The second could be a label they gave themselves for seeing the signs of the Fall, and fleeing aboard a ship in advance until they found a secure island in the far north where they could try to rebuild.

I love your connection between Zachry’s polished story and Luisa’s polished story. I missed that.

I like the idea of the Prescients calling themselves that because they were seeing signs of the Fall: this would suggest an almost cult-like mentality, perhaps, as well as an arrogance that we know the Old Uns had: WE see what’s coming, WE know the truth.

(Also, apologies to you–I managed to post the unproofread draft of this last night, so you had to stumble through rather a few typos. This is the cleaned up version now!)

They’re a bit condescending, but the Prescients are still an improvement over their Adam Ewing analogue (the Europeans encountering the Moriori before the Maori show up and enslave them). They fairly trade with the Valleyfolk, and even their planned migration was in the context of trying to help the Valleyfolk and other islands (as well as living with them in order to minimize the impact of the migration).

I agree they’re an improvement, but I’m not sure they weren’t out for themselves in their study of Big I as a possible new home. I have the feeling they’d have moved in and tried to help “for the the good of the Valleysmen” while doing what colonizers have done throughout history: take over and make sub-classes, even if they think they have good intentions. Had the Prescients succeeded in moving in, would they have continued to keep the remaining Smart for themselves? Would they have aided the Valleysmen in the Kona attacks, or held themselves aloof as the white men did during the Maori/Moriori conflict? Hard to say…

I did not find the Prescients to be condescending at all. Any condescension was the perception of Zachary, fueled by his mistrust.

True, we’re definitely seeing this through Zachry’s eyes, and Zachry is taking pains to show how much he didn’t trust them. But at the same time, their “prime directive”-style way of dealing with those who have less Smart than them is something I find questionable. Why do they choose to let people die when they do have the ability to save them, for example? Why, even, would she say her ship runs by fusion power but not take the time to explain what that is? The Prescients have a natural aura of a superiority when dealing with the “primitives” that echoes the way the white colonials of Adam’s time deal with the Maori.

Another parallel of the Prescients and the white Chatham colonists is that, despite supposedly superior firepower, they could only stand by and watch as the predatory natives (Kona/Maori) slaughtered and enslaved the more peaceful, Valleysmen/Moriori). Ewing seems to judge the colonists for their inaction, but Sloosha’s Crossing shows powerless they really were.