Introduction

Part 1: The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing (first half)

Part 2: Letters from Zedelghem (first half)

Part 3: Half-Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery

The Story So Far . . .

The third of our six nested stories in Cloud Atlas is the first that reads like a novel, not a true-life account. It’s a third-person, mostly omniscient, and present tense narrative. It also starts with the most direct link to the previous story of all of the narratives, beginning, “Rufus Sixsmith leans over the balcony…” (p. 90). Sixsmith, of course, is the recipient of the letters written by Robert Frobisher in part 2. It’s 1975, 44 years after those letters were written, and Sixsmith is an old man and eminent scientist who meets a 26-year-old journalist named Luisa Rey when they get stuck in an elevator together.

Luisa is the daughter of admired cop-turned-Vietnam reporter Lester Rey, who recently died. She’s cutting her teeth as a gossip columnist for Spyglass magazine and hoping for an opportunity to write about something real. Sixsmith is harbouring a secret that might get him killed, and passes along just enough information to get her interested. They talk for an hour and a half, the duration of the blackout that has trapped them in the elevator, trade stories (she tells stories about her dad, and about interviewing Hitchcock, he talks about his beloved niece, Megan), and Sixsmith remarks that “I feel I’ve known you for years, not ninety minutes” (p. 96).

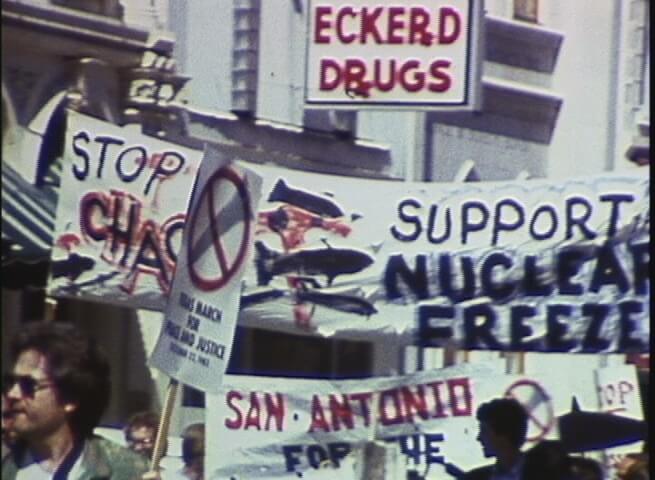

Freed from the elevator and arriving home, Luisa finds 11-year-old neighbour Javier has broken into her apartment again. She lets him crash with her whenever his mom is out all night, which apparently is often. Tonight he is also sporting a welt on his face, from a “friend” of his mom’s. Not a great life this kid has, it seems. She grants him the security of sleeping on her sofa for the night. The next morning at a pitch meeting at the magazine, Luisa listens to the veteran reporters making up tabloid stories, alleging drunken presidential antics and man-eating piranhas living in sewers. Luisa pitches Sixsmith’s story: that Seaboard, the tenth largest corporation in the country, has covered up serious design flaws in its new nuclear reactor just off the coast of Buenas Yerbas, California. Seaboard already has one reactor running and is about to unveil its second, with plans for a third. Her boss scoffs at her and tells her she can only run the story if she has hard evidence to back it up, a stipulation he didn’t require from the male reporters’ stories.

Driving out to Swannekke Island, the reactors’ home, Luisa is welcomed to the facility by Fay Li, the publicist. Luisa claims that Spyglass wants to raise their editorial standard and run a day-in-the-life-of-scientists piece because of the new reactor’s grand opening. She’s immediately spotted by Joe Napier, head of security who is not far from retirement, and who ruminates on the eleven scientists he and Seaboard’s security team were able to intimidate into “forgetting” a nine-month inquiry into the design flaws of the power plant. The twelfth scientist, the one they couldn’t silence, is, of course Rufus Sixsmith, who is in hiding after writing a damning report about the reactor’s lack of safety.

Luisa sits in on the grand opening speech made by CEO Alberto Grimaldi. Grimaldi hands over the podium to Federal Power Commissioner Lloyd Hooks. The two exchange muttered unpleasantries beneath their big smiles for the cameras. Luisa slips out and finds Sixsmith’s office, where she meets scientist Isaac Saachs, who assumes she is Sixsmith’s niece, Megan. He demands to know where Sixsmith is hiding, and then Fay Li comes in and removes Luisa. Luisa plays dumb, claiming that she’d met Sixsmith ages ago and had an appointment to chat with him while she was on Swannekke.

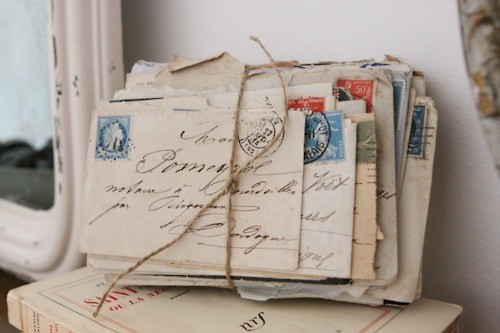

Sixsmith, meanwhile, is watching the ceremony on TV as he calls Megan. An unfamiliar male voice answers and tells him to get out of the country because “they” are coming for him. He takes the call seriously, goes to the airport, deposits the Sixsmith Report in a locker there, and mails a package to Luisa that contains the key to the locker. He then books the first available flight for England, which departs the next day. He takes a hotel room to wait for the flight, where he looks over his most prized possessions: a bundle of letters from “his unstable friend, first love, and if I’m honest, my last,” Robert Frobisher (p. 111). These are, of course, the letters of part 2. They are deeply worn and well read, and Sixsmith knows them by heart. He reads the first nine in the series and takes the rest with him to read at the hotel restaurant over dinner. Returning from his meal, he lays down on the bed, and is promptly murdered by the Seaboard-hired assassin Bill Smoke, who shoots him in the head and leaves the gun and a typed suicide note at his side.

Luisa sips her morning coffee at her usual diner and is shocked to read about Sixsmith’s “suicide.” She immediately assumes he was murdered, and goes to the hotel to investigate. Accused of being a “ghoul” who is just after a story, she claims she is Sixsmith’s bereaved niece and is given the only thing left in his room, the packet of nine letters. The omniscient narrator tells us she passes within ten yards of the locker in which Sixsmith hid his report. She goes back to work, is chewed out by her boss for going to Buenas Yerbas to pursue the story, and bargains her way into a stay of execution: she has until the following Monday to deliver the hard facts to back up the story or she has to drop it.

An interlude occurs from the point of view of a used record store employee, taking a call from Luisa, who has read Robert Frobisher’s letters and is looking for a copy of his musical work Cloud Atlas Sextet. The employee tells her Frobisher was a wunderkind who died young, and that only five hundred pressings were made of the music but that he can probably track it down for her—for a price.

Bill Smoke watches Luisa and learns where she lives. She, meanwhile, reads and re-reads the Frobisher letters, totally disconcerted by them: “It is not the unflattering light they shed on a pliable young Rufus Sixsmith that bothers Luisa but the dizzying vividness of the images of places and people that the letters have unlocked. Images so vivid she can only call them memories” (p. 120). She is further disconcerted by the mention of the comet-shaped birthmark between Frobisher’s shoulder blade and collar bone, a birthmark identical to her own. She claims she doesn’t believe in “this crap,” but clearly she’s thinking reincarnation. She is seeing the Frobisher letters in more detail than she should.

Luisa goes back to Swannekke, this time to talk to the encampment of protesters outside the power plant. She talks to Hester Van Zandt, whom she refers to as “Doctor,” and who is a leader of sorts for the protesters. Hester tells her that the land they’re using belongs to Margo Roker, a woman who refused to sell her land to Seaboard and who was horribly attacked in her own home by “burglars” who didn’t happen to take a single thing after beating her unconscious. She remains in a coma, and Hester all but says the burglars were Seaboard assassins, especially since a front corporation owned by Seaboard is now offering Margo’s relatives four times what the land is worth.

http://www.texasarchive.org/library/index.php/Category:The_Alan_Frye_Collection

Next, we get to see the story through the eyes of the evil Alberto Grimaldi, CEO of Seaboard. Grimaldi has a briefing with Fay Li, Joe Napier, and Bill Smoke, to talk about how much of a threat Luisa is. Dismissing the other two, Grimaldi and his assassin Smoke have a tete-a-tete. Grimaldi congratulates Smoke’s excellent work with Sixsmith and points out that accidents should be ready for both Lloyd Hooks and Luisa Rey.

Back within the power plant for her fictitious day-in-the-life piece, Luisa is reintroduced to Isaac Sachs, who Sachs insinuates that he might be able to get her the report, but that he is afraid to do so. They make plans to get together the next morning, but instead of Isaac, Luisa is met by Napier, who claims Isaac had to go to Three Mile Island at the last minute to work. He shows her around in Sachs’ place, and we glimpse a surprising fact. Joe clearly knew Luisa’s father from his cop days (and is deeply uncomfortable with the idea that Luisa might need to be “dealt with”): “Of all the professions that lippy little girl could have entered, of all the reporters who could hae caught the scent of Sixsmith’s death, why Lester Rey’s daughter? Why so soon before I retire? Who dreamed up this sick joke?” (p. 135).

Meanwhile, Fay searches Luisa’s hotel room for the report or any clues to its whereabouts. Fay has cards up her sleeve, too: she’s not looking for Luisa’s knowledge of the report for Seaboard but because she wants to sell the report to a rival oil company, who will pay handsomely in order to discredit atomic energy. Later, the two women go to dinner, where Fay tries to bond with Luisa over the chauvinism they face as professional women in the 70s. Fay hints that she might have information to pass along. Though curious, Luisa doesn’t trust her enough to take the bait.

Later that night, Luisa’s awakened by a long-distance call from Isaac, who tells her that he’s given Garcia a gift for her. She understands after a moment; during their drinks together, she told him her VW Bug’s name is Garcia. He must have put the report in her car and is afraid the conversation is being recorded. Sure enough, she finds the report in a garbage bag in the trunk, and upon hearing Napier calling out her name, makes a break for it. Smoke instructs the gatekeeper to allow Luisa off the island. On the open road, he rams into her car with his own, forcing her through the barrier and into the sea, where he assumes she will die.

Some Thoughts…

This section is said to most closely resemble an “airport novel,” a quick and cheap paperback that you buy at the airport, read on a plane, and toss when you land. The present tense seems out of place in the genre to me, and the reading and language level is somewhat higher than the average pulp book. That said, Mitchell creates some wonderfully overwrought phrases that match the genre well, such as “Wednesday morning is smog-scorched and heat-hammered” (p. 112). The characters are stereotypical and larger than life in many cases, including the villainous Alberto Grimaldi, the smooth and cold Bill Smoke, and the eighteen-months-to-retirement Joe Napier, who of course just happens to know our plucky heroine. The stakes are also higher in this story than the previous two–we’ve moved from the small, personal problems of Adam Ewing and his Ailment or Robert Frobisher’s debts to safety concerns that could rain nuclear winter down onto America’s west coast, all in the name of money.

The theme of predacity is apparent on a number of levels in this story. We have Seaboard ignoring hard scientific fact and the possible loss of countless lives in order to make a lot of money. We have the individuals within Seaboard, specifically Alberto Grimaldi and, at his orders, Joe Napier and Bill Smoke, menacing scientists into silence. Less lethal but no less dishonest are the journalists at Spyglass, making up stories about serial murderers in order to frighten people and entice them into buying the magazine, of course. And in the most individual example in this section, we have poor Javier, who is often abandoned by his mom and who is threatened and beaten by the men his mother knows. We also have willful neglect, with several characters quite happily turning a blind eye to bad deeds in order to save themselves or at least to avoid hardships.

But just as important, to me, is the flipside of predacity: compassion. Luisa has no real reason to take care of Javier. She is in no way connected to him or his mom except for the fact that they live next to each other, but she takes care of him anyway because she is a compassionate person. Or, when Isaac talks about how afraid he is to go into detail about the Sixsmith report, Luisa tells him to do “whatever you can’t not do” in order to save lives or preserve the truth (p. 133).

In the third straight story are many examples of systemic prejudices. Though the racism here is not quite as blatant as in the first two sections, it’s nonetheless there under the surface, for example when the journalist Jerry Nussbaum is telling his “heroic” tale of escaping a mugging by “six dreadlocked freaks of the negroid persuasion” (p. 107). But much more prominent than racism in this section is sexism. Luisa’s male co-workers constantly ask her if she needs help or advice, in a disparagingly paternalistic way, or making blatant sexual statements to her, such as when she tells Nussbaum to kiss her ass and he replies “In my wettest dreams…” (p. 100), causing her to be “torn between retaliation—Yeah, and letting the worm know how much he riles you—and ignoring him—Yeah, and letting the worm get away with saying what the heck he wants.” Fay Li expresses similar issues to Luisa, talking about an engineer who propositioned her: “What would you do? Dash off some witty put-down line, let ’em know you’re riled? Slap him, get labeled hysterical? . . . Do nothing? So any man on site can say shit like that to you with impunity?” She laments that perhaps one day women will live in a liberated world, but the world they’re in now is nowhere close. For someone like me, pushing thirty and having never had deal with this kind of blatant bullying, this belief that I am inferior simply because of my gender, it is mind-boggling to think that this kind of attitude was pervasive around the time I was born.

Stories within stories within stories are happening here, and subtle connections are made backward and forward within the book. The fictional Buenas Yerbas, where much of this story takes place, is in California at a time of the flourishing of atomic energy, and links quietly back to Adam Ewing, who is also from California at the time of the Gold Rush. Questions of authenticity become murkier in this section. This seems quite obviously to be a novel, from the subtitle, “The First Luisa Rey Mystery” to the tone. (Indeed, the title itself is something I adore, half-lives referring of course to radioactive, to the way these characters might not be living complete lives, and also to the way we’re only reading half of each story.)

So this is a work of fiction in which the character Luisa is reading the nine letters we read in part 2, in which the character Robert Frobisher read a journal written by Adam Ewing. This certainly muddies the idea of what is “real” and what isn’t within the framework of Cloud Atlas. Or is this a novel based on real events, as shown by the existence of Robert Frobisher’s almost-forgotten music? That so few examples of his music remain match eerily the comment he makes (posted at the end of Part 2 of the readalong) that a composer is but a scribbler of cave paintings, and that no lasting immortality should be sought through music.

This question of immortality, and an echoing of Ayrs’ hopes for his music, is seen in Luisa’s assessment of Alfred Hitchcock: “He spoke in bons mots like that, not to you, but into the ear of posterity, for dinner-party guests of the future to say ‘That’s one of Hitchcock’s, you know'” (p. 95).

And, with regard to immortality, we also get the question of rebirth, of lives lived and re-lived, of mistakes made and re-made, in the fairly pronounced suggestion that Luisa is Robert Frobisher reborn. Even as she should be hurt by her ex-boyfriend’s appearance, instead “her mind walks the passageways of Zedelghem chateau,” a place she has never been but memories of which have somehow been evoked by the letters of a man who died before she was born, and with whom she shares the same comet-shaped birthmark (p. 122).

What do you think of this section? Did you find it faster paced? More interesting? Less well written? What do you think of the shift to fiction from true-life first-person narratives? What do you think of the omniscient point of view, and of all of the extra detail we get about other people’s lives here, including Luisa’s mom and ex-boyfriend? Does Javier play an important role? What are your thoughts on Luisa Rey’s mystery?

You might also like:

Another significance of the name “Half Lives” relates to something which has confused many readers: Luisa Rey and Timothy Cavendish, if they both exist on the same plane of reality, appear to be reincarnations of the same “soul”, and yet, given their ages, they are alive at the same time. We might assume, then, that when Cavendish reads “Half Lives”, he is, without realising it, reading about the “other half” of his own life.

I know that this may be long overdue but I recently started reading the novel, I must admit it seemed a bit boring at first but “Half Lives: The First Luisa Rey Mystery” really had me going. It is a very interesting novel which am sure I will enjoy. I have reached “An orison of Sonmi-451.

Overall, I’ve found this book to be perfectly compelling, and I found this section to be engrossing, although very different in style. As it’s been mentioned in the other comments: it takes skill to be able to write in a more ‘mediocre’ fashion.

The theme that I’ve found to be most fascinating in the novel as a whole is the ‘validity’ of the previous sections. In Zedelghem, Frobisher doubts the authenticity of Ewing’s journal, and the style of this section, written as a novel, even mocks the validity of everything we’ve read thus far.

I only have one question regarding this section. How did Luisa Reyes know the name of Frobisher’s Work: The Cloud Atlas Sextet? This part of the novel says that Luisa only received the first nine letters, which are the ones before this chapter, yet these letters don’t mention the his sextet’s title.

Anyway, this readalong

…has been helpful, to say the least. Being a non-native English speaker, reading this helps me make sure I didn’t skip anything, which is great help.

And whoops, I accidentally pressed the ‘submit’ button before I was done. I guess typing on a cellphone has its drawbacks.

I enjoyed the faster pace of this section. It was a bit refreshing. Plus I really got into the story, and found the pages started flying by. That being said however, I don’t think it is less well written. Just written differently. We still see a lot of the same themes, and Luisa herself was fascinating to me. She was struggling to live up to her father’s reputation, dealing with loss of her relationship etc but she still fought to find the truth, even when it would have been easier (and safer) to walk away. One line that really stood out to me was when she’s talking to Sachs and she says “Do whatever you can’t not do” (p 135). I thought this was really representative of her character as a whole.

I also resisted a huge temptation to flip ahead and see how her story ends, the first part stopped so abruptly! But I resisted and now it’s on to part 4!

This is definitely one of the bigger cliffhangers in the first half, though personally I found the end of part 5 even more of a “Ohmigawdwhathappensnext?” moment.

I love the “Whatever you can’t not do” line too.

It’s written very well in a deliberately less style, in my opinion. Mitchell is going for the more popular narrative with the bigger tropes, the obvious characters that everyone can identify, the quick plot twists and turns, etc., and he’s doing it with much more obvious language. And it takes great skill for him to do that, I think.

I ended up loving Timothy Cavendish’s story far more than I remembered the first time ’round. Can’t wait to hear your thoughts on him!

I like the fast pace of this section. But it is one of my least favorite because it’s a bit predictable and as Timothy says in the next section: (the young-hack-versus-

corporate-corruption thriller) it’s been done a hundred times before.

I think a lot of people feel this way about this section, and I think it’s totally intentional on Mitchell’s part. He has done the very difficult job of a gifted writer, namely writing poorly. Or at least writing in a more mediocre way than he normally would.

I loved this section. It reminded me of something I read once that was written by the great Science Fiction writer Isaac Asimov, about how it takes a good writer to write a convincingly stupid character in a compelling way. Luisa Ray’s not a stupid character (for the most part), but it’s definitely a mark of Mitchell’s skill as a writer that he was able to write a compelling section with a plot that silly.

Excellent catch about women and power in this story, which is not coincidentally set in the 1970s (an important decade for Feminism). It’s another aspect of the Predacity Theme.

I think the random detail about the boyfriend (an occurrence which has no real connection to the greater story and leads nowhere) is just another sign that the First Luisa Ray Mystery novel is a badly written story. In fact, if you take the story as thinly veiled wish fulfillment on the part of the “Hillary Hush” author (which seemed likely after reading the 2nd Cavendish section), then this would probably represent “her” inserting something that happened to her into the story.

The “Mom” sections have more relevance in the 2nd Half of the Luisa Ray story.

So true. It’s like the problem of casting Sally Bowles in the musical Cabaret. The character is a two-bit, not particularly talented singer, and you need a truly great singer to be able to pull off the job of singing poorly in the musical.

I love Timothy Cavendish’s dismissal of the Luisa Rey novel, that it was written by someone envisioning it as a movie, that its writing style is “artsily-fartsily Clever.”

Is this your favourite narrative of the six?

I like it, but it’s not my favorite out of the six. My favorite is Sonmi 451, followed by Frobisher and Ewing (mostly because of the moving end to Ewing Part 2, when he comes to his realizations about what he needs to do).

It’s been long enough since I first read this book that I don’t have a strong memory of the second Adam Ewing section. Sonmi is my favourite too, and I actually found I enjoyed Cavendish far more this time than the first time around. The tonal shift into comedy is such a change and respite from the darker goings-on.

In just a few paragraphs we know exactly the time period in which this story takes place. Its almost comforting how easy this section is to get into and yet the story is oh so not comforting at all. I think the writing is equally as good as other sections but so different, that I am reminded of the brillance of the author. This is the second reading of this book for me; I loved it so much the first time that I have been a bit reluctant to re-read in case I am disappointed. That is not the case at all, in fact I have a renewed appreciation for this work all over again. Still not sure how a movie version will work though….

You’re so right. And the ease of reading this one sits in the midst of some of the more difficult sections in a similar way to the mirrored, nesting overall structure.

What do you think of the various tangents that happen here? We get a lot more about the lives of Luisa and those around her than in the first two sections, including the interludes with her mom on the phone and the ex-boyfriend, Napier’s deceased wife Millie and his plans for retirement, Dom Grelsch’s health issues, etc.

I’m pretty thrilled to say I have a ticket to see the movie at TIFF in less than two weeks….I’m so nervous and anxious to see how it translates to the big screen.

I think for this story the tangents are necessary just based on the plot alone. I don’t remember the second part of this story but I bet the detail will be necessary. Also these details get you so hooked into the story and the people. I am worried about Javier, I care about Luisa, I am thinking about Megan.

Can’t wait to hear your thoughts on the movie. I wonder if David Mitchell will show?! Not sure when I will get to see it.

” Its almost comforting how easy this section is to get into and yet the story is oh so not comforting at all.”

It so warmly reminds me of watching “Kojak” or something like that when I kid. But indeed, now, it is a very sinister turn of events.

Definitely faster paced-liked the added detail, it made Luisa more “human”- that may be the wrong word, but it made me feel more involved in the story. Can’t quite figure out Javiers purpose in the story.

I enjoyed the fast-paced nature of this section too. It’s interesting how stepping out of the first-person POV can give us a more complete picture of who the protagonist is. We don’t have Luisa’s voice telling us what she thinks of Javier, but we do have the narrator showing her judging Javi’s mom but also taking Javi in whenever he needs help.

It’s far more in fashion for third person limited viewpoints right now–we see only what Harry Potter sees (with a couple of exceptions). How different would Harry be if written like this section, dropping into the thoughts of Dumbledore and Hermione and Snape and Dudley? Or if the narrator gave broad hints and commentary about opportunities Harry missed as he’s missing them, not after the fact as he discovers his own error? I think it’s a great choice Mitchell has made with this section because it fits the timeline and genre this section was supposed to be written in, not unlike, say, a Robert Ludlum book.