“Ultimately, it’s a book about crossroads.”

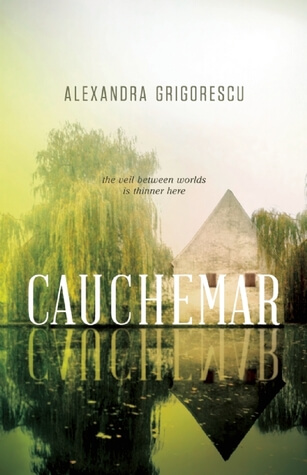

In Cauchemar, debut author Alexandra Grigorescu weaves some extraordinary magic. This sultry southern gothic tells the story of twenty-year-old Hannah, raised in the Louisiana swamp by Mae, a midwife who relies a little more on voodoo than Hannah ever realized. When Mae dies unexpectedly, Hannah is thrust into two worlds, opposite in nature but just as dangerous—the distrustful townfolk Mae has kept her isolated from, and the sinister sorcery of Hannah’s witchy birth mother…

As quickly as Alexandra Grigorescu evokes the robust spices in deep south cooking, she sends shivers up your spine at the mention of something white and scaly sneaking through Hannah’s dreams…and into her reality. Alexandra stopped by the blog to answer a few questions and share an excerpt from chapter two of Cauchemar.

Alexandra, thank you so much taking the time to discuss your mesmerizing book with me. Let’s start with perhaps the most mysterious question of all: What led a Canadian in (currently very) snowy Toronto to set a book in the deep, swampy south?

Thanks so much for having me, Dee, and thank you so much for your kind words. Winter’s the perfect time to start taking a mental vacation to somewhere warmer, and nothing transports me quite like writing.

But the answer to that question lies, I think, in a quick little story: When I first started writing Cauchemar, I was living in this tiny bachelor apartment in Toronto, and I was dating my now-husband. We were in the early days of the spring thaw. I was taking a step back, assessing the vista of my life, and I had that fingertip itch to just write .

I’d discovered a nearby salvage shop (The Chief Salvage Co.), which was brimming with old B&W photos, jewelry, and bones that were sometimes sourced from the South. I’ve always had an affinity for bones, and I fell head over heels for this sun-bleached cow skull, lightly cracked and missing a few teeth—a bovine Yorick. I spent what was, to my newly unemployed self, a bit of a fortune on it, and mounted it as the only significant decoration in that small space. I’d positioned it, without meaning to, so it was reflected in the mirrored closet door. Everywhere I turned, I saw that skull, from morning to night. Thing is, that skull didn’t look like a cow’s to me. It seemed like a relic. It felt like parched coral. In the morning light, it looked almost reptilian.

I started writing the book, and it quickly became vaguely supernatural and decidedly Southern. I think I’ll always blame (and thank) that skull.

Have you lived in or visited Louisiana? What is it about the foods and music that have so obviously captured your imagination?

My husband and I visited Louisiana, and there’s not much about it that wouldn’t capture the imagination. We took a boat ride on the Atchafalaya and there’s something about the Spanish moss and those old trees rising from the water that’s instantly suggestive of some in-between place. The food is wonderfully spiced, incredibly rich, and not easily forgotten. Frenchmen Street is one of my finest memories, with its bars full of patrons breathlessly spinning each other and brass bands spilling into the street. This is fiction, though, so I took some liberties.

What kind of research did you do specifically for the magical/spiritual aspects of the story? Is Christobelle’s “church” based on reality? What other traditions influenced this story?

Christobelle’s a strange case. She’s not a spiritualist or a medium–she’s something quite malevolent—so her practice is, as far as I know, not based in anything real.

The orishas, and other practices such as voodoo, are incredibly complex, and I regret that I wasn’t able to explore them more fully on the page. In reading about the traditions of the South, I got the sense that there’s some disagreement even among those who live there about what they mean, how they should be interpreted, and how they manifest.

As I was writing Cauchemar, I discovered an interest in superstitions and folklore, particularly those that are shared among different cultures. As an example, the experience of cauchemars in the South bears resemblance to the Hag (a common superstition throughout history) or the Persian Bakhtak. These are all essentially describing sleep paralysis. I find it fascinating that a medically observable condition has so many folkloric iterations, some of which have moral or punishing components.

Sexuality plays a big role in Cauchemar—from Hannah’s early, confused explorations with Sarah Anne to her relationship with Callum that quickly leads to pregnancy, as well as the strange power Christobelle exerts over her followers. Can you discuss this?

Sure. Sexuality, I think, plays a big role in life. I think part of sexuality is being open to experimentation and being rewarded by intimacy. Sexuality can also signal complete vulnerability, which sometimes goes hand in hand with the threat of pain or danger.

I didn’t intend to have Hannah’s relationship with Sarah Anne unfold as it did, but it felt right to me once it was on the page. Christobelle falls somewhere in the tradition of a succubus, I think, but I don’t think of her relationship with her followers as being sexual, do you? I imagine it as a chalk-dry, thirsty thing.

The theme of duality resonates throughout you book, twins who show two sides of the same coin. Darkness and light, bad demons and good orishas, Christobelle’s gift of death and Mae’s gift of life, even the isolated swamp versus the bustling town. Were you consciously playing with this idea of duality?

Not consciously, I think, but it ended up coming through in so many aspects of the book. Ultimately, it’s a book about crossroads. It’s an interesting shape if you think about it—the opposed finding common ground, even if it’s fleeting. It’s a strong image, and I think I had it in mind as I was headed towards the book’s conclusion. Everything was rushing towards that one moment of impact.

You can only ignore a crossroads if you stand still (which would make it a dot, really), so it comes down to making a choice. A lot of the book’s duality comes from choices, specifically as they relate to Hannah. It’s a bit of wish fulfillment that your choices would be in such stark contrast, but hopefully by the book’s end, it also becomes clear that a lot of these differences are not as defined as they might seem.

To that end, the question of safety is a big one—what does it mean to be “safe”? How can the home that has protected Hannah from what is waiting for her start letting things in instead of keeping things out. Can you talk a bit about the imagery and symbolism in Hannah’s house in the swamp?

What is safety to you? It might be one of those words that only becomes personally defined once it’s gone. I think it’s deeply troubling to find your four familiar walls offering no protection, particularly when what’s outside is so threatening. The edge of a swamp is a dangerous, isolated place in most people’s mind, but for Hannah, it’s a safe space. As she quickly realizes, though, the physical structure of the house (which is literally torn apart over the course of the book) does not equal a home, and it’s actually the latter that made her feel safe.

I hope that’s as recognizable a distinction for the reader as it is for me—no walls can keep out fear, but the ineffable essence of a home (love, comfort, and belonging) is strong stuff.

Can you talk about using horror as a way to explore the way we deal with grief and loss?

Grief and loss are a horror, at least in the private moments when we let ourselves feel them fully. They can change you into something frightened, or even frightening. They can undo you. But they can also instruct you to deal more tenderly with those who are here. Death is an end you can’t negotiate with, and that’s a tricky thing to wrap your head around: it boggles the mind.

The white alligator isn’t necessarily a symbol of grief, but the way it’s dealt with throughout the book can be seen as a sort of signpost for the way we deal with, and move through, the pain of loss and the fear of what comes next.

Where did the story start for you? Was it always about Hannah and her baby? When did Sarah Anne and Jacob enter the picture?

I have what might be an unusual approach to writing. It usually starts with a particular image or a sentence that worms its way into my head and won’t let go—everything else begins from that kernel. I write whatever’s there to write, and then I put the puzzle pieces together.

It began with Christobelle, but this book didn’t feel like her story, so Hannah was a way to observe Christobelle’s world—just to dip my toes in. Insofar as I was writing what I knew, I knew what it meant to be twenty-something, and ever so slightly unsure about what came next.

It was interesting to play with the Rosemary’s Baby notion of an unborn child because it offered up so many questions. Will the child even be born? Which side of the duality you described will it land on? Will Hannah survive?

Sarah Anne and Jacob were there almost from the very start. I wanted to have an element of Hannah’s childhood as a way of giving context for her choices and behavior.

Did you ever creep yourself out as you wrote? You definitely creeped me out (in the best possible way!) as I read.

I’m so glad I creeped you out! I’m a sucker for horror flicks, and watched Twin Peaks at what most would consider too young an age, so I suspect I have much more, much worse scares in me.

Much of what unnerved me most while writing it were the emotional stressors, and finding that I was willing to risk the characters, without quite knowing that they’d make it back.

Who are some of your influences?

Honestly, too many books, movies, paintings and albums to list. As far as this book goes, I think writers who do horror well—Stephen King, Patrick McGrath, and Nick Cutter (who I discovered not too long ago and just can’t stop raving about) to name a few—have a real gift. It takes chops to frighten someone, and to maintain that particular pitch of high tension. Josh Malerman’s Bird Box is a great example of housebound horror done beautifully. Tony Burgess’s People Live Still in Cashtown Corners is a treasure.

Just in general, Ian McEwan, Barbara Gowdy, and Ann-Marie MacDonald will always be something so, so special to me. A single line of Anne Carson generates neurological fireworks.

Music also stokes my creative fires: I was listening to Bela Fleck and Abigail Washburn, and Mirel Wagner’s incredible (and unnerving) self-titled album during the final edits on Cauchemar.

What’s next?

Stay tuned. Who knows, I might even find my way back to the South one day.

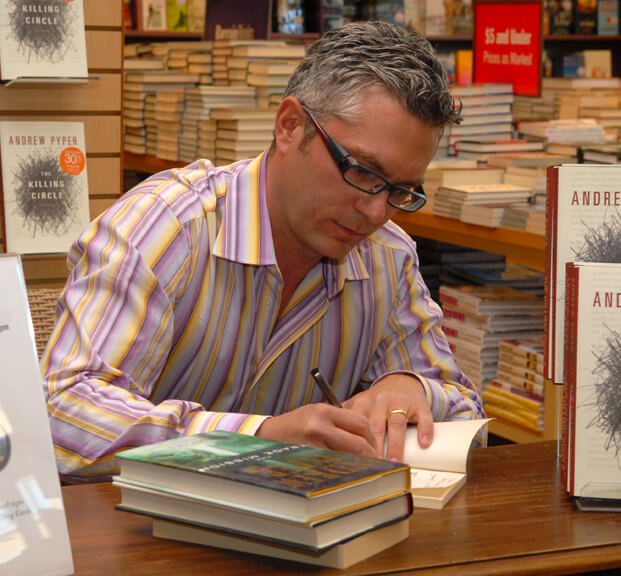

Thanks to ECW Press for a review copy of Cauchemar and Alexandra Grigorescu for her thoughtful and beautifully worded answers! And now, here’s a sneak peek at chapter 2 of Cauchemar:

Follow the tour!

March 1: The Book Binder’s Daughter, http://thebookbindersdaughter.com, Review + Giveaway

March 2: Bibliotica, http://bibliotica.com, Review + Guest Post (the use of food to enhance the story)

March 3: Bella’s Bookshelves, http://www.bellasbookshelves.com/, Review + Excerpt (Ch. 1)

March 4: Write All the Words!, http://www.ekristinanderson.com, Guest post for International Women’s Week feature

March 5: EditorialEyes, https://editorialeyes.net, Interview + Excerpt (Ch. 2)

March 7: Lavender Lines, http://lavenderlines.wordpress.com, Review

March 9: Svetlana’s Reads, http://sveta-randomblog.blogspot.ca, Review

March 10: The Book Stylist, http://thebookstylist.wordpress.com, Review + Interview

March 11: Booking it with Hayley G, http://bookingitwithhayleyg.blogspot.ca, Review + Guest Post + Giveaway

March 12: Dear Teen Me, http://dearteenme.com, Guest post (letter to teen self)

March 13: The Book Bratz, http://thebookbratz.blogspot.ca, Review + Giveaway

March 14: Feisty Little Woman, http://feistylittlewoman.wordpress.com, Interview + Excerpt (Ch. 3)

You might also like:

|

A review of The Winter People by Jennifer McMahon

A review of The Winter People by Jennifer McMahon