Violent political realities in Sierra Leone and their lasting physical and psychological traumas form the backdrop of Michael Wuitchik’s gritty debut My Heart is not My Own. neck.

“By evening, the heat of the day has thickened like a smell. P’tit finally falls into a snuffling doze in her locked arms.

A tap at the door. . . Jenny Bonnet, the pool of purple around her eye faded to greenish yellow, the swelling gone down. It was only two days ago when the thug walloped her chez Durand, Blache calculates. That was in Blanche’s old life, before she brought P’tit home.”

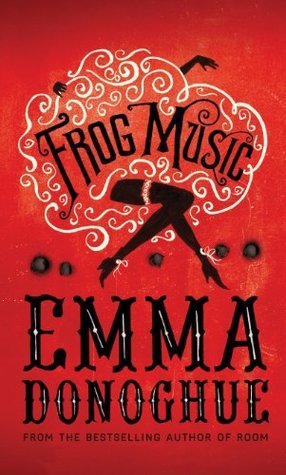

– Frog Music, Emma Donoghue

San Francisco, 1876: During an unbearable heat wave and a dangerous outbreak of smallpox, Blanche Beunon bends over to unlace her boots and bullets fly over her head, killing her new friend Jenny Bonnet almost instantly. Blanche is sure her lover and his best friend are behind it, that the bullets were meant for her. Jenny, a prototypical coucher surfer who makes her living catching frogs for restaurants and has done jail time for her habit of wearing men’s clothing, was simply in the wrong place. But can it be more than that? From the notorious House of Mirrors where Blanche dances to Chinatown where she and her lover live, Frog Music draws a picture both bright and bleak of post–Gold Rush San Francsico and brings to life a real unsolved murder.

Blanche, a former Parisian circus performer, pays the bills as a celebrated burlesque dancer and sometime-prostitute, and has saved enough money to buy the rooming house in Chinatown in which she and her lover Arthur live. Arthur and his friend Ernest live la vie boheme, which for them mostly means living off and freely spending Blanche’s earnings. Everything changes when the trouser-wearing frog girl Jenny accidentally drives her high-wheeler bicycle into Blanche. She follows the dancer home and asks some guileless but uncomfortable questions that cause a series of tragic events to unfold. In particular, Blanche realizes how little she knows about the “farm” where she pays to have her and Arthur’s one-year-old son P’tit fostered. The narrative jumps back and forth between the murder and its aftermath and Jenny and Blanche’s burgeoning relationship and the havoc caused by the reintroduction of the baby into Blanche, Arthur, and Ernest’s carefree lifestyle.

The present tense narration puts the reader directly into the action. This immediacy makes us remember that these aren’t just characters, but living, breathing people. I love this kind of historical fiction. Donoghue has meticulous research skills and an immense imagination. She gives us a huge, intricately woven tapestry: San Francisco is as much a character as a setting here. From restaurants and saloons to bawdy houses to parks, everything is created in vivid detail. We can see the the little yellow flags hanging outside doors, feel the horror that smallpox resides within. The stifling heat wave, the brimming xenophobia, the glorious multiculturalism, and the expansive freedom our post-Prussian-war main characters feel in America makes for a delicious reading experience. And the mystery of who shot Jenny, and whether the killer had meant to aim for her or for Blanche, is satisfyingly convoluted. Many different characters have means and motive, and the fact that Jenny’s death is already inevitable tinges even the fun and intimate scenes with tragedy.

Blanche is a fascinating heroine, a woman in the 19th century who genuinely loves sex and is entirely comfortable with her sexuality. She’s fashionable, shrewd with money, and not maternal. Her fight for her baby is far more a matter of will and a sense of duty than love or instinct. This is a refreshing take on motherhood and womanhood. Too, Blanche’s emotional journey is engrossing: from blithe ignorance and meek submission, letting Arthur call the shots even though she is the breadwinner, toward a fuller sense of self-worth. The best moments of the novel come when she is interacting with the boisterous Jenny. Though Blanche makes her living as a burlesque dancer and prostitute, she is in many ways the upright, buttoned-down straight woman to Jenny’s quite literally free-wheeling, jolly, criminal life.

As charming as the high-wheeling, cross-dressing frog hunter is, because we only see her through Blanche’s point of view, and only in the flashback scenes, there is something of a detachment that occurs. Jenny never comes as alive as I wanted her to, remaining closer to a caricature as Blanche realizes how little she knows about her new, dead friend. The mystery of Jenny’s back story is compelling, and way she and Blanche connect so deeply and yet at the same time almost not at all, makes for the best kind of readerly frustration: you want more for these women than history has allowed them to have.

Frustrating in a less appealing way is the choppiness of the chronology. There is no real need to jump back and forth so much. The reliance on flashbacks rather than a straightforward timeline took me out of the narrative somewhat, rather than compelling me forward, and made it difficult to see Arthur and Ernest as the villains of the piece. It strains credulity somewhat that Blanche lived so closely with them for nine years, only to be turned on so quickly and fiercely. And because Donoghue incorporates so many historical, well-researched characters, at times the facts seem almost too crammed in, as though the ghost of each person gets to make a quick cameo in this fictionalization of their story.

Frog Music is nevertheless well worth the read for its lush historical detail, seedy glimpses into San Francisco’s underbelly, and twisty, turny, totally plausible explanation for who killed the real life frog catcher Jenny Bonnet. Blanche and Jenny, caught up in their tragedy, will stay with you long after you finish reading their story.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Three and a half out of five blue pencils

Three and a half out of five blue pencils

Frog Music, by Emma Donoghue, published in Canada by HarperCollins, © 2014

Available at Amazon, Indigo, and at fine independent bookstores everywhere via Indiebound.

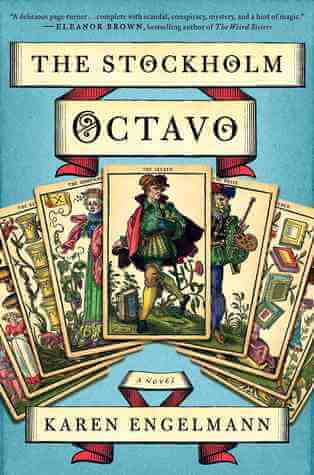

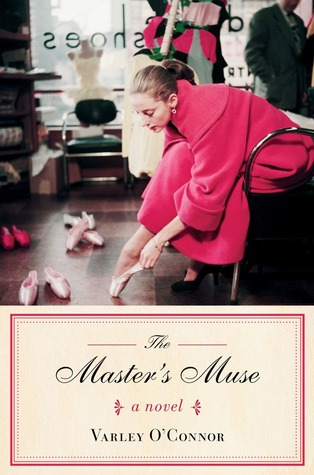

You might also like:

Great review (I linked to it in my post)! It’s a fascinating novel. I loved the way Donoghue brought the historical context to life. I also thought Blanche was a fascinating character, but I didn’t think she was a refreshing take on womanhood and motherhood. Her life made me sad, and I kept wondering if her insistence about her “desires” was really a coping mechanism.

I have this book as well and I’m looking forward to reading it! Blanche sounds like a really interesting character. I like female characters who are comfortable in their own skin/sexuality. Too bad to hear there’s a bit of detachment as far as Jenny goes!