Sometimes I forget how amazing—and how connected—our world is. Then, I find myself in a movie theatre, watching a live performance of the famed Bolshoi Ballet, beamed around the world to me via satellite. Cineplex offers a fantastic opportunity to see ballet (and theatre and opera) from esteemed troupes around the world, and seeing it at the exact moment it’s happening on a stage somewhere far away. I have never experienced the Bolshoi in person, but I have seen them live several times over the past few years thanks to this technology.

I happily attended Sunday’s production of La Bayad ère, not quite sure what to expect. I’ve never seen a Canadian company offer this ballet before, though I was aware that it is a Marius Petipa ballet, with music by Ludwig Minkus, the team behind other ballets including Don Quixote. What I witnessed was a mixed bag of flawless dancing and deeply troubling choreography, storytelling, and cultural stereotypes.

La Bayadère is the story of Nikiya, a temple dancer, and Solor, a warrior. They have sworn to be true to each other, but fate, as it so often does, especially in ballet, has other ideas: the high Brahmin at Nikiya’s temple is in love with her and wants to do away with his rival. A nearby Rajah has decided that Solor should marry his daughter, Gamzatti. The high Brahmin informs the Rajah of the young warrior’s love for the temple dancer. Bad things happen, and Nikiya ends up being bitten by a snake after she dances at her beloved’s engagement party to this other woman. Rather than taking the Brahmin’s antidote and living without Solor, she chooses death. Confused? Don’t worry about it. The third act has almost nothing to do with the first two: Solor, horrified, dreams of her that night and follows her into the “Kingdom of Shadows,” a mostly decontextualized third act that is far more about choreography and the beauty of dance than it is about the story. This third act is often presented on its own, without the rest of the ballet.

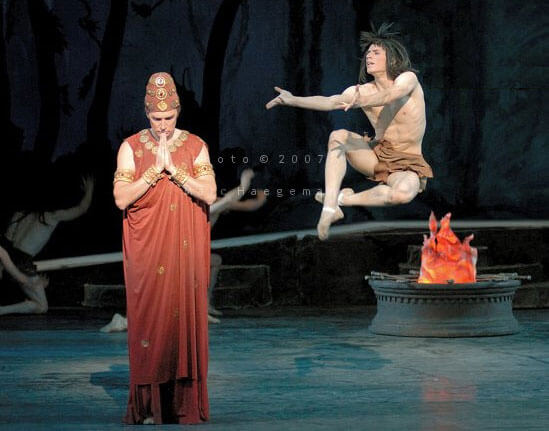

So, to the Bolshoi’s production, and the place of this ballet in 2013. In terms of technical skill, the Bolshoi is generally second to none. Further, the dancers are also all terrific actors, portraying a broad and convincing range of emotions through facial expression as much as through movement. As Solor, Vladislav Lantratov leaped with grace and power, displaying the brash nobility of a warrior and the broken heart of a lost lover. Maria Alexandrova was stunning as his second choice, the Rajah’s daughter Gamzatti, holding the audience captive with every perfect movement. Svetlana Zakharova, in the title role of the bayadère Nikiya, was fluid and flexible but so painfully thin that she was often uncomfortable to watch. Perhaps it’s a low blow to talk about a ballerina’s physicality (as we saw when New York Times ballet critic Alastair Macaulay called the totally healthy and beautiful Jenifer Ringer fat back in 2010), but Zakharova’s boniness, each individual rib, the visible ulna and radius in each forearm, was distracting and worrisome. (Here she is, embracing Solor: http://youtu.be/jllgIkHgFR0?t=19m17s)

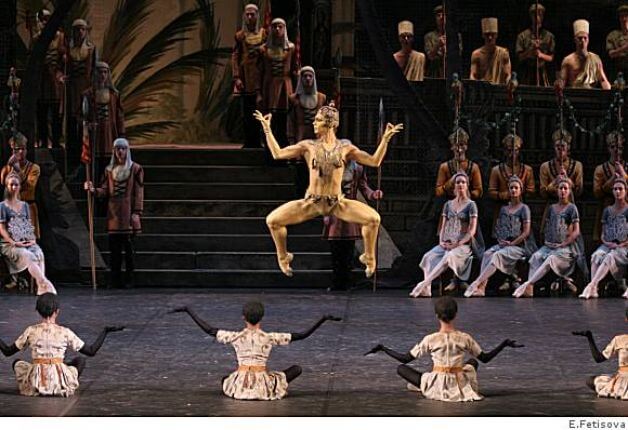

The three create and work the angles of a compelling love triangle, with Nikiya’s choreography otherworldly, pliant, and fluid, and Gamazatti’s strong, with bold lines and athletic leaps. This ballet presents one of the only female fight scenes I can think of in the classical canon, as the women go head to head over Solor. It’s good see the women taking their fate into their own hands (and brandishing knives at each other, yet; it’s right up there with Mercutio and Tybalt duelling). This is by no means a feminist tale, of course, as their fate is ultimately decided by the men, and Nikiya decides it’s better to die than to live without Solor. The third act is transcendentally pretty, as the entire female corps move down a snaking ramp, repeating the same arabesque sequence, seeming to refract or reflect the image of Nikiya over and over. Take a look (this is the Paris Opera Ballet):

So, those are the positives. I could happily watch that third act without any of the stuff that comes before it. Because, oh, the problems with this ballet. Where to begin with La Bayadère ? One of Marius Petipa’s many ballets, it is said that he and composer Minkus were inspired when real Indian “temple dancers” toured Russia. Petipa is the choreographer and ballet master behind Spanish-flavoured ballets Paquita and Don Quixote, Byron-inspired Le Corsaire, and such iconic works as The Nutcracker, Giselle, Cinderella, The Sleeping Beauty, and the most famous version of Swan Lake. As was the fashion throughout many cultures in the 1800s, Petipa latched onto the “Exotic Other,” creating ballets that were about mythical or faraway places and times, about settings and people exotic and different from his own. In the case of La Bayad ère, Petipa set his ballet in “ancient India.” It does not appear that he did research beyond possessing a vague knowledge that India has temples, rajahs, and harem pants. The story is not derived from any Indian source. The names are not Indian. The religion depicted is. . . honestly, I don’t know what it is. There’s a temple in the background that houses a random golden statue (a bit like a Buddha with a topknot) and there is a sacred flame attended by, well, cavemen, as near as I could tell? The temple is run by the High Brahmin, who you can tell is in charge because of his big red robe and fez (yes, his fez).

The scenes scream of orientalism, an essentializing, stereotypical, often patronizing and generally false depiction of Asian culture by Western, or “occidental” cultures, often with an emphasis on mysticism: this a story set in a dark and distant land full of strange people who are unlike us in custom and dress, purely for the purpose of spectacle. Several of the dancers portraying monks are in saffron robes and are wearing skullcaps to appear bald, seeming to be Tibetan Buddhist transplants in this ancient Indian jungle.

Oh, and did I mention the children in blackface? Because that happened. I can’t find a clear image of the shocking costumes the adolescent dancers who portray young Indians are made to wear (and that might be a good thing). They have full black spandex body suits, covering feet hands, even fingers, and their face are painted brown, seriously. The offensiveness was only compounded by the 19th-century choreography in which the children hop around like monkeys. Children in blackface, portraying “ancient Indians” onstage in 2013. Here they are in the ballet: http://youtu.be/jllgIkHgFR0?t=24m8s

So, we have an all-white cast performing a ballet over a century old that is based on this one time some Indian dancers came through Russia. Is it fair to criticize Bayad ère when other ballets cut broad strokes against other cultures? Giselle, for example, might not showcase an accurate portrayal of the Rhineland in the Middle Ages; Don Quixote might be a bit liberal with its Barcelona setting, but it, at least, is based on the Cervantes novel. As well, Don Quixote nods toward Spanish music and dance. Sure, in Bayad ère there are the aforementioned harem pants and the dancers occasionally raise their hands intertwined above their heads—based perhaps on what Petipa saw the visiting temple dancers do. But that’s it. Just as insidious as the overtly racist imagery, if perhaps a bit subtler: nothing here evokes India whatsoever apart from these very few flourishes.

Sure, the sets show a temple in a jungle, but the story of the common woman whose noble lover is to marry a noblewoman instead of her, and who therefore kills herself/chooses death, and spends the final act as a ghost is just Giselle with elephants. And, in this case, cavemen. The story isn’t Indian, the names aren’t Indian (Gamzatti? Nikiya?), and the costumes are passingly Indian only in a “we saw some Indians wearing something like this, sort of. Maybe. Also, we added in a bunch of tutus” way. Minkus’ score is musique dansante style, which is to say it’s polkas and waltzes and sounds like every other ultra-Euro-Russian score of the time. Not a step of Petipa’s choreography strays outside classical ballet repertoire. This story might as well be set in a made-up land for all it has to do with anything on this earth, and in 2013, how can that be okay when it is, in fact, meant to be set in India? The cultural appropriation and racism is shocking.

La Bayad ère reminds me of being a young dancer when we were choosing what our competition pieces would be for a given year (“This year we’re hippies! That means we’ll wear bellbottoms and our hair down and swing our arms like this!” “This year we’re Can-Can dancers! Yips and high-kicks and big skirts!”), putting on the costumes and settings of other time periods or cultures. Even so, our music and choreography always reflected and were influenced by the choice of dance setting. Petipa’s Bayad ère has none of that, however. This kind of cultural stereotyping was commonplace in the 1800s and much of the 1900s. Just look at Bugs Bunny in blackface in now-banned 1950s cartoons. Or consider Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom from 1984. Its depiction of the bloodthirsty high priest of the human-sacrificing Kali cult (who is somehow capable of thrusting his hand into a man’s chest, pulling out his still-beating heart, and throwing the man, still living, into lava) isn’t so different from Bayad ère ‘s interpretation of Hinduism. It’s meant to evoke shock and exoticism. It isn’t in any way an accurate portrayal of real people.

Certainly we have to be careful in saying that an all-white cast can’t use dance to tell a story set in another geographical and cultural space. The flipside of that argument might be, for example, that an Indian dance troupe can’t perform Romeo & Juliet because they aren’t white and British (or Italian, come to that). This kind of essentializing is dangerous. Dance can and should transcend cultural boundaries. But it needs to do so in a thoughtful and sensitive manner, borrowing and celebrating rather than appropriating and misrepresenting culture.

In 2008, Manitoba’s Rainbow Stage mounted a version of J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, another stickily racist Victorian tale, a play that usually portrays Aboriginal peoples as “red Indians” whooping and war-calling all over the stage. The theatre company rethought and restaged these scenes with a traditional First Nations hoop dancer and culturally accurate and sensitive costumes and actors, creating a stunning setpiece and bringing new life and depth to the play. Should La Bayad ère be struck from the ballet pantheon? Not necessarily. I’d love to see the story made new with actual Indian dance choreography worked into the ballet, with a bit more attention paid to where and when the story is set and how it might actually operate in the culture in which it is supposed to take place.

In the meantime, I don’t recommend seeing the traditional version of La Bayad ère. This is indeed an amazing and connected world we live in, and one where a greater understanding of our fellow human beings—not strange Other people—is a necessity. With so many other classical ballets in their repertoires, companies can do better than this terribly stereotypical, orientalist old clunker. It’s time to update the temple dancer or put her out to pasture for good.

You might also like:

|

Review of the National Ballet’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland |

Review of The Master’s Muse

Review of The Master’s Muse

Review of Girl Reading, by Katie Ward

Review of Girl Reading, by Katie Ward

Interesting.. I had not read this perspective before, but when I watched the Ballet, I had the same reactions. Being an Indian , it’s particularly hurtful. But I chose a different path: I am a Bharatnatyam dancer, and so I chose to re-imagine the dance, in a more appropriate (Bharatnatyam) form. We are premiering this weekend in Fremont, CA. http://www.dikshaadanceacademy.com

Oh my. I don’t really know what else I can say. Err… I’m glad I didn’t come with you to see this performance? Not that it makes you feel better!

It’s funny that you mention First Nations hoop dancers. I was just thinking back to last summer when I went hiking in Crawford Lake conservation area. On its grounds is a pre-contact archeological site, which led to the construction of a replica 15th century Iroquoian village – all very cool stuff (longhouses are awesome… plus it’s a lovely hiking destination). Anyway there was this special event on while I was there, and I saw traditional First Nations dancers in full regalia. But from a distance, one of the dancers looked caucasian. I suspect he was 1/4 or 1/8 aboriginal, not that I really care: he danced well, and I didn’t look at him and think “white guy”… I thought “skilled dancer”. Both 100% genetically aboriginal and 100% genetically non-aboriginal people (and everyone in between) should be able to perform traditional dance, provided they were taught well and respect the culture. Which brings me to my point: it really ought not to matter what ballet dancers’ colour of skin is. Yes, let’s see an East Indian woman as Juliet. Is her dress similar to what one would have seen in Italy in the middle ages? Do her movements, gestures, and facial expressions show love and heartache? Does she dance well? That ought to be more than sufficient, no?

I really enjoyed reading your thoughts about this production. I recently read “Imperial Dancer: Mathilde Kschessinska” by Coryne Hall. It was an interesting read about the ballet world in Russia when Petipa was active. Thanks to your post I’ll be checking out Cineplex for upcoming presentations – I didn’t know that they did this kind of thing – great!