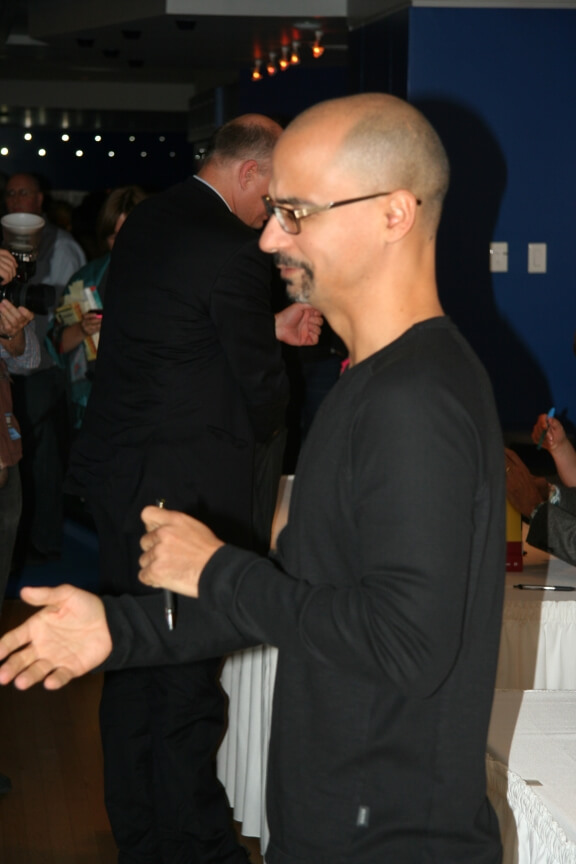

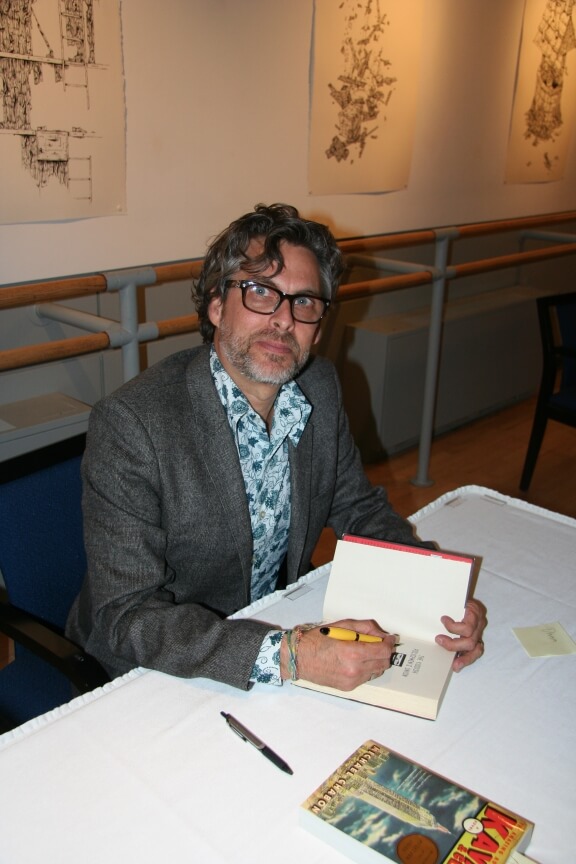

The International Festival of Authors couldn’t have picked a better duo for one of their opening events: Junot Díaz (This is how You Lose Her, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao) and Michael Chabon (Telegraph Avenue, The Yiddish Policemen’s Union), talking about their books, the nature of fiction, the problems of modern book criticism (or lack thereof), writing women, writing race, the awesomeness of Michael Ondaatje, and the double standard in genre fiction. They also read from their books, took audience questions, and were terribly funny and swore a lot. As you might guess, it was a hell of a good 90-minute session.

“Are you ready for some literature?” asked moderator Siri Agrell, author and columnist who was hilarious in her own right and held her own against her formidable guests. The sold out crowd most certainly was. The opening night buzz was palpable (made even cooler for my friend and I by a heated debate about whether the gentleman waiting in line in front of us was Michael Ondaatje. It was. I’d expect him to get his own IFOA throne or something, but he queued along with us normal folk to go and see a lit event. So cool!)

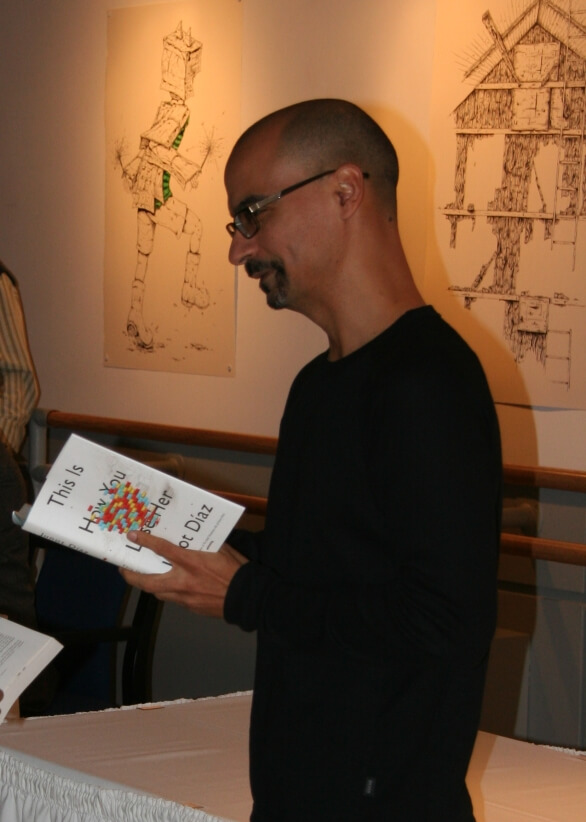

The readings: Michael Chabon began by expressing his gratitude that he was to share a stage with Díaz, grinning and boasting to us, “I thought he was awesome before you did.” Then he read from Telegraph Avenue, an excerpt about a vinyl recording of a song the characters are listening to, a jazzy, turned-inside-out version of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “I Don’t Know how to Love Him.” Junot Díaz then took the stage and was just as admiring of Chabon: when Chabon was first published, “everyone who was a writer thought ‘oooh, we’re in fuckin’ trouble’.” Both authors seemed so genuine in their respect for each other. Díaz read from the final story in his new collection This is How you Lose Her, a searing second-person narrative about Díaz’s favourite protagonist, Yunior, and how he screws up the great love of his life. Díaz’s delivery was wonderfully natural, a guy mocking his buddy for being a moron, showing the humour in a desperate, sad situation.

The discussion: Guiding everyone into the discussion section of the evening, Agrell joked that she thought she would get to sit between the two, becoming a Pullitzer sandwich. Both authors were in a New Yorker “young authors to watch”-type spread, and are supporters of each other’s work. “Do you monitor those magazines for new threats?” Agrell asked, and Díaz replied no, “the best part about books is you can put many on a shelf.”

On language and the f-bomb: Both authors are known for their authentic voices, their narratives that sound the way people actually talk. Chabon was deeply influenced by Raymond Chandler and John Updike, writers who could be poetic and colloquial at the same time. Díaz’s Spanish-laced academic/street slang coarse American English helps to evoke one of the most authentic narrative voices I’ve ever read. He points to the lack of cues writing has when it comes to dialogue; words on the page can’t create the silences between words or the way people stretch or emphasize a certain syllable, and so Díaz denies that his writing is actually the way people talk, but creates a believable rhythm of its own to approximate this quirks of language and extra-linguistic cues.

Which leads, as it must, to the question of cursing: so many classics both old and new veer away from swearing (Agrell pointed to The Art of Fielding and the complete lack of curse words to be found in the all-male jock locker room scenes), but Chabon and Díaz both embrace it in their writing. Chabon, in fact, was the first person ever to have a story with the word “fuck” in it published in the New Yorker: it was integral to a scene and apparently there was a lot of editorial debate about how to take it out before deciding to leave it in. “I paved the way for you,” he told Díaz. “I sit around with my gratitudes all day,” Díaz replied.

On the act of writing; How, Agrell next asked, does each author go about planning a new writing project? Quite differently, it turns out: Díaz might have a character or an exchange in his head that he wants to write, or he might have a strategic concern that is much larger or more abstract; for example, he wanted to examine the after-effects of how many women were raped in the Dominican Republic under the Trujillo dictatorship, which became a large part of the lives of the characters in Oscar Wao. Chabon came to writing because he loved the maps in the childhood books he was reading. He would superimpose the map of the world in his book with the map in his head of his own world, and so he likes to build the world of his book first at this intersection of cartography and storytelling.

Acknowledging those who came before: In building their worlds, both authors expressed surprise at the lack of acknowledgement in modern writing. There is a sense, Díaz said, that one must be an insular genius whose every idea springs fully formed and not informed by those who came before. Or, perhaps worse, there is often the abandonment of “base” sources for loftier ones. This, he told us, was bullshit: you listen to interviews with George Lucas the year Star Wars came out and he’s citing Flash Gordon and comic books and sci-fi as his inspiration. Five years later when asked what his sources were, he replies “Oh, The Iliad.” “We’re not fucking God,” Díaz said. “We’re not generating this shit out of our own brains!” He draws from The Fantastic 4, Tolkien, all sorts of comics, from many other writers. “Oh sure, you’ll be back here in five years talking about Dickens as your inspiration,” Agrell teased him. “Sure, swearing and talking about Dickens. So I’ll get my peanut butter in your chocolate,” Díaz quipped.

Gender, Race, Genre, and Talking Around Books: The discussion of acknowledgements brought up an interesting question about literary criticism today; Díaz recalls seeing an article in the New York Times complaining that a book’s acknowledgements were too long. How strange, he said, that we would waste space talking about this, but not talking about the content of the book itself. Especially when there’s so much room to go around for writing about books in modern media, Chabon deadpanned.

Regarding gender, Both Chabon and Díaz are widely agreed to write good female characters, which not all male writers are always good with. Diaz runs his female characters by women in his life. As a professor of creative writing, he says women tend to write men better than men write women. Somehow, men always include a “boob moment,” he said, in which the main female character touches, looks at, or otherwise contemplates her breasts in ways he doesn’t think women really do. “A student can say ‘this is my Vietnam War book,’ and there in the rice paddy, the woman looks down at her chest…”

And what about race? When Agrell asked whether, say, a white writer can write from a black perspective, Chabon said he never thought about it in those terms while writing his black characters in Telegraph Avenue because he was just in their heads thinking about what they would do. He was, though, worried when he wasn’t writing about how the characters would come across. Díaz pointed out that he’s more interested in the question of privilege here: people will ask “is it okay for white people to write about black people” but not “is it okay for Asians to write black people,” and so on. He sees this as just another way of talking around a book, rather than about the content of the the book, about what the book is trying to do and trying to say.

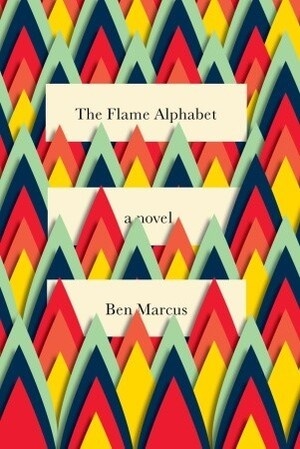

The question of genre writing also came up, and again, it was seen as a question of privilege and of talking around books: if a genre writer, Díaz said, wrote a book about zombies, that writer wouldn’t get profiled in the Times, wouldn’t be reviewed, might sell a few thousand copies. But if Díaz writes a genre book, because he’s considered part of the literary firmament, everyone will say “Oh my God, he wrote a book about Wookies?!” and he’ll get all sorts of attention. “Does that seem fair to you?” Diaz asked a member of the audience, that they could write the exact same book, but Díaz would be hailed for his and the audience member would languish in obscurity.

Ondaatje: One of the loveliest moments of the evening occurred during the audience Q&A, when someone asked what it’s like to find the exact word to fit into a sentence, like a missing puzzle piece. Díaz referred to a particular line in Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient, when the character Kip notices the colour of everyone’s hands around the table. Someone in the back of the theatre shouted “He’s here! Michael Ondaatje is here!” Sure enough, the fellow my friend and I had been eyeballing was Michael Ondaatje. Incredible moment to be a part of, to have such a talented writer on stage praising the work of another talented writer without realizing he’s in the audience. “It’s an honour,” Díaz said humbly. Michael Chabon stage-wiped his brow and said, “Thank God, I was going to say that book sucked!”

Everyone laughed. Everyone cheered. It was that kind of night, a celebration of literature to kick off a whole week celebrating literature.

You might also like:

|

|

Sounds like such a fabulous event! I love when the author’s are really engaging, it makes the night fly by and everyone has a good time. And that Michael Ondaatje moment is so cute!

It’s always hit or miss, and some authors (no names named 😉 ) are just not good at these types of events. It’s always a bit worrisome when you go to see someone you really enjoy and they don’t meet your expectations in person. These guys exceeded them. I’d love to take a class with Junot Diaz…no, actually, I’d love to *audit* a class with Junot Diaz. I think he’d be a really hard marker 😉

Hey, glad you had a good time! Was not the most relaxing night I’ve ever had!

I can imagine! They didn’t give you an easy time, but you handled the evening very well! And you were very funny 🙂

Sounds like you had a great time. And OMG Michael Ondaatje! 🙂

So, how do I stop feeling like a loser because I don’t know who Michael Chabon and Junot Díaz are? They sound like excellent writers and really cool people. So many authors, so little time to read their work…

I could have leaned over and *touched* Michael Ondaatje. He was that close to us in line.

I will lend you books!