Introduction

Part 1: The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing (first half)

Part 2: Letters from Zedelghem

The Story So Far…

“Letters from Zedelghem” is the funny and affecting second section of Cloud Atlas. Though from a first-person perspective like “Adam Ewing,” this section is not in journal entries but rather is written entirely in letters. The writer is a rakish, bisexual (or perhaps simply opportunistic), musically gifted and financially strapped Englishman named Robert Frobisher.

July 29th, 1931—Frobisher is writing to his friend and, it’s hinted, (former?) lover Rufus Sixsmith throughout this section, and he begins by recounting how he is awakened in his hotel in London by a debt collector’s thugs hammering his door down. Making his escape from both the thugs and his hotel bill out the bathroom window and down a drainpipe, he hides in Victoria Station and ponders his fate. Should he borrow money from his estranged family or the classmates from the Cambridge college he was kicked out of, or take an entirely different and somewhat crazy option…

You see, Frobisher has an idle daydream in which he visits a reclusive British expat composer who lives outsider Bruges, Belgium. Vyvyan Ayrs, described by Frobisher as “one of the greats,” is ill and mostly blind, and hasn’t produced new music in a decade. And Frobisher wishes to offer himself up as an amanuensis—both to find shelter against his debts and because he genuinely reveres Ayrs’ music and wants to help make more.

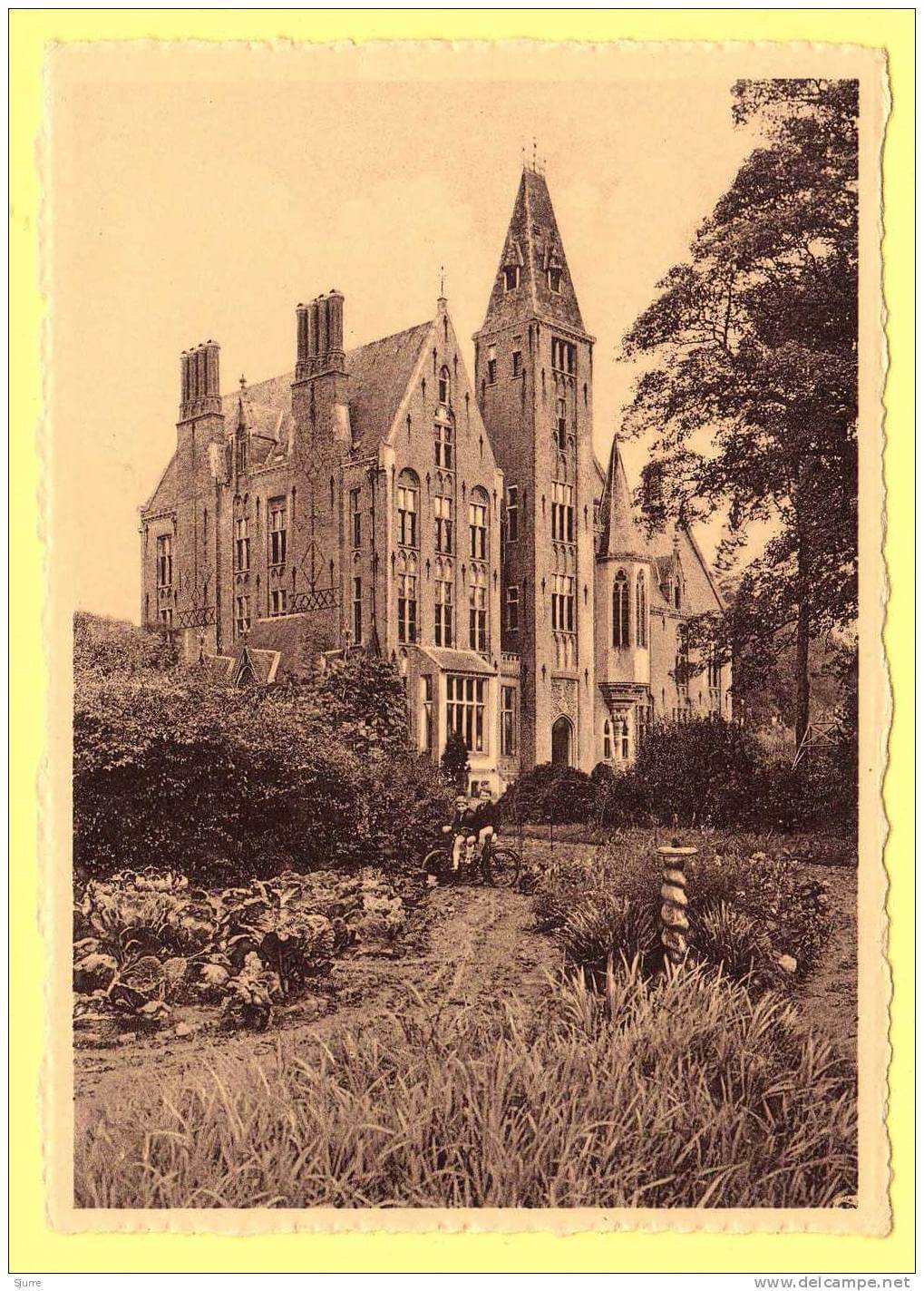

So, over to Bruges he sails with the very last bit of cash in his pocket. He presents himself at Chateau Zedelghem and arouses the old composer’s curiosity. He is allowed to stay the night in order to audition the next morning.

He then recounts his audition. He and Ayrs immediately rub each other the wrong way. As he awaits the pronouncement of his fate, he meets Ayrs’ daugher, 17-year-old Eva: also not a good start. Supping with Ayrs’ wife, Jocasta, Frobisher learns that Ayrs liked his audition, and that Eva is “uncivil” most of the time but rooms in the city while going to school during the week, so he won’t have to endure her much if he stays.

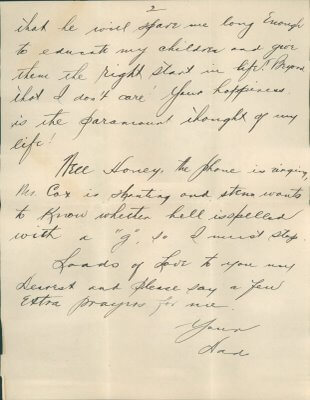

July 6th—Admonishing Sixsmith for sending a telegram, which could draw unwanted attention, Frobisher also refers to a letter Sixsmith has from Frobisher’s parents. He dismisses his father’s concern as centering on nothing more than irritation that the debt-collectors have come calling. He is intent on keeping his financial and familial woes quiet lest his mission at Zedelghem be questioned.

The next morning, Frobisher is summoned to the music room, where Ayrs bellows out a melody without repeating it, slowing down, or naming the key, time signature, or any notes. He then mocks Frobisher’s abilities to Jocasta, establishing his dominance over Frobisher entirely. Miserable and unsure of his position or future at Zedelghem, Frobisher begs Sixsmith for a small loan.

July 14th—Frobisher thanks Sixsmith for the money. Having been admonished by his wife, Ayrs apologizes and acknowledges to Frobisher that “music is oxygen to us both,” and agrees to the amanuensis scheme. The two musicians develop a working routine as well as a daily one that includes meals with Jocasta, time for Frobisher to compose on his own, and visits from many colleagues and friends to Zedelghem.

At this point, Frobisher realizes how much he values Ayrs musicologically, and how much more valuable these networking experiences are than his years in university were. He also grudgingly compliments Eva’s intelligence in spite of his insisted dislike of her. Methinks he doth protest too much.

Amongst working with Ayrs and bickering with Eva, Frobisher also explores the library and lays the groundwork with Sixsmith to steal some of the older, more valuable books, with the intent of selling them to book dealer Otto Jansch and pocketing the cash. He also mentions a book he’s found that’s been torn in two. It’s the published version of an old journal written by an American notary in the 1850s, and he’d like to read the second half, if he can find it.

July 28th—Celebration! Ayrs and Frobisher complete their first work together, “Der Todtenvogel,” The Death-Bird. Frobisher exults that some of the ideas and phrases within the work are all his own (though he will get no credit for composing). He seems to be happy just to be part of the process. He also discovers that Ayrs’ wife, Jocasta, is flirting with him.

August 16th—Into August, the two become lovers even as Frobisher continues to collaborate with Ayrs, whom Jocasta says contracted syphilis in a Danish bordello and hasn’t touched her since 1915. He confesses to no guilt but rather exalts a bit in his secret when Ayrs mocks one of Frobisher’s compositions in front of houseguests.

On the musical front, Todtenvogel has become a controversial success, full of daring new ideas no one expected from Ayrs at his age. Eva, meanwhile, continues to question Frobisher’s place in the house and his shady background, and Frobisher agrees to meet with Jansch in Bruges, per Sixsmith’s arrangement.

So, faking a need to meet with a family solicitor in Bruges, Frobisher actually meets with Otto Jansch, the book dealer. They haggle over prices, and then Jansch suggests another transaction Frobisher might find lucrative. In spite of several anti-Semitic and just kind of mean slurs to Sixsmith regarding Jansch, Frobisher happily sleeps with him, takes his cash, and has a nice afternoon. While out, he sees Eva in the company of an older, married gentleman, and though he insists he doesn’t like her, he is surprised that such an attractive girl would end up with such a bad prospect. When she returns home on the weekend, he confronts her and she tells him the married man is the patriarch of the family she boards with during the week. Frobisher tries and fails to save face by claiming he was worried about her, not trying to blackmail her.

August 29th—Bedroom farce! While in flagrante delicto with Jocasta, who should appear at Frobisher’s door but her husband. Jocasta hides amongst the bedclothes and they trust Ayrs’ blindness to save them. It works, as Ayrs puts Frobisher to work on a melody, a “seesawing, cyclical, crystalline thing” (p. 79) Ayrs heard in a dream. He confides, “I dreamt of a…nightmarish cafe, brilliantly lit, but underground, with no way out. I’d been dead a long, long time. The waitresses all had the same face. The food was soap, the only drink was cups of lather. The music in the cafe was…this.” Ayrs then asks Frobisher if Jocasta has ever come on to him. Frobisher works himself up into indignation and denies it, even as he feels Jocasta’s breath on his thigh beneath the covers. Upon Ayrs’ exit, Jocasta seems angry that Ayrs loves the boy she has taken as a lover.

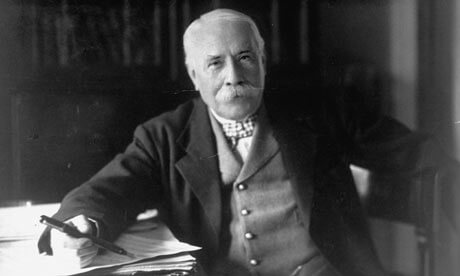

September 14th through 28th—Sir Edward Elgar visits, much to Frobisher’s delight. That delight soon turns to arrogant dismay, however, when Elgar praises Todtenvogel and Ayrs thanks Frobisher as an “aide-de-camp.” “Aide-de-camp? I’m his bloody general and he’s the fat old Turk reigning on the memory of faded glories!” Frobisher fumes (p. 83). This shows quite a change in demeanor and the way he sees his role from July when he was just happy to help out. In the last few letters of September this arrogance increases, with Frobisher all but making Ayrs beg him to stay on even as Frobisher grows weary of Jocasta’s clinginess.

Some Thoughts…

This is one of my favourite sections of Cloud Atlas. Eminently more readable than Adam Ewing’s writings and therefore rather like a breath of fresh air, Robert Frobisher is also a deeply funny narrator, both when he means to be and when he doesn’t. “Spud-faced young steward and I disagreed his burgundy uniform and unconvincing beard were worth a tip,” he sniffs (though he goes on to sleep with said steward, and still refers to him as “spud-faced,” though also as “inventive for his class” [p. 46]). This section is full of Frobisher’s by-the-seat-of-his-pants charm and his classist disdain. As he squares off with Ayrs during the audition, the old composer demands “Go on. Impress me.” Frobisher asks what he should play, to which Ayrs responds, “I must select the program, too? Well, have you mastered ‘Three Blind Mice’?” Indignant, Frobisher riffs out a rendition of that very tune “after the fashion of a mordant Prokofiev” (p. 52). I snickered at his turns of phrase throughout.

The way Frobisher breathes music is beautifully authentic, too. It informs his entire way of seeing the world. Everything is music to him, and as much as he might be a fop, a poseur, and an out-and-out thief, his talent and his love for music are both quite genuine. Of Elgar and Ayrs sleeping by the fire, he quips, “Made a musical notation of their snores. Elgar is to be played by a bass tuba, Ayrs a bassoon. I’ll do the same with Fred Delius and Trevor Mackerras and publish ‘em all together in a work entitled The Backstreet Museum of Stuffed Edwardians” (pp. 83–84). As he ponders his fear of poverty while hiding from the collection thugs, he thinks, “Had a view of an alley: downtrodden scriveners hurtling by like demisemiquavers in a Beethovian allegro. Afraid of ’em? No, I’m afraid of being one. What value are education, breeding, and talent if one doesn’t have a pot to piss in?” (p. 44).

What strikes me here, more than anything, is how different the narrative voice is, let alone the style, between the first two sections. Adam is as earnest and honest as Robert is flippant and thieving. Adam’s is written in the style of Melville while Frobisher’s reads like Wodehouse. It is in reading section two that I began to fall in love with David Mitchell as an author and an auteur. It takes serious talent to pull off two such different voices.

And speaking of the two sections, we begin to see references forwards and backwards in time in this narrative. On page 64, Frobisher writes about half a book he’s discovered in the Zedelghem library, a “journal [that] seems to be published posthumously,” written by an American notary during the Gold Rush by the name of Adam Ewing. Though fascinated by the story, and frustrated that he has only the first half (“A half-read book is a half-finished love affair,” he laments), he also questions the book’s authenticity, suggesting it is too structured, with language that doesn’t quite ring true. What to make of such claims? Did Adam Ewing truly exist? Are we only reading his words through the eyes of Robert Frobisher, who only has as much of the journal as we do? What exactly can we believe is “true” here?

Frobisher also makes mention of the birthmark “in the hollow of my shoulder, the one you said resembles a comet,” (p. 85). This reference will pop up again (and also hints at the relationship that Frobisher and Sixsmith share or once shared). As we’ll see in a few weeks, Ayrs’ odd dream, in which he sees servers, all with the same face, in a strange cafe at a time when he is long dead, will indeed come to pass. Dreams seem to be playing an important role here. Just as Adam Ewing writes about his nightmare in his journal, Robert Frobisher recounts his own bad dream in which he crouches in a trench, “savages” patrolling around him riding giant rats.

Some lovely nods and meta references appear throughout, as well. In particular I like that one of Ayrs’ pieces is called Matryoshka Doll Variations, which calls to mind the nesting, mirrored structure of the stories of Cloud Atlas. That Frobisher mentions Frederick Delius is a nod to the inspiration for this section. As David Mitchell says in an interview with the Washington Post, “a book by Frederick Delius’s amanuensis, Eric Fenby, Delius: As I Knew Him . . . gave me the idea of Fenby’s evil twin, and the struggle between the exploited and the exploiter.” Again we encounter the theme of predacity. Who is exploiting whom more in this relationship?

Frobisher is making two major journeys here, neither of which bode particularly well for him. On one front, he seems to be setting himself up to take Ayrs’ place, feeling more and more of claim on the music they have made together, helping himself to the books in the library, charming the visitors, and of course slepeing with Ayrs’ wife. Jocasta herself is a clue to this, being named after the queen whom Oedipus weds after Oedipus kills her husband. You know how that story goes . . . it is Oedipus’ own father whom he has murdered. Jocasta whom he weds, is in fact his mother. Frobisher is thus set up as an oedipal figure, looking to depose the father figure Ayrs.

Frobisher is a deeply individualistic and self-involved narrator, and this section, accordingly, occurs far more on the individual than the societal level. Even as Ayrs tries to assert his dominance over Frobisher, and Frobisher beings to think that he is more important than Ayrs, we also see a number of ways that individuals deceive and hurt one another. Jocasta has affairs her husband can only guess at, and both she and Frobisher lie about it. Frobisher lies to himself about his growing fascination with the young Eva, he keeps lies by omission about his financial insolvency, and he also outright steals from Zedelghem’s library for his own monetary gain. At no point does he show any flicker of guilt or moral confusion over sleeping with Ayrs’ wife or stealing his books. There isn’t any more justification than “I wanted it so I took it.” He has no issue with prostituting himself for actual cash, or for information or protection. One also wonders just what he’s done to be thrown out by both family and school. These letters are from his point of view and to a sympathetic party, so of course he is painted as the put-upon victim, but surely in spite of his musical genius he’s kind of a rotten human being.

The fact that we only see Frobisher’s letters also adds an air of authenticity to this section, in the same way the publisher’s footnote from Adam Ewing’s son suggests that the diary is a real one. If we were to see both sides of the correspondence, or letters to and from other people, the story would be more complete, as in Nick Bantock’s Griffin and Sabine books or The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows, but it would also read like a novel, and not like a packet of letters that someone has received and kept from an old friend.

We also see the ascent/descent themes here, again on the smaller, individual scale. Frobisher starts his narrative off by scaling down a drainpipe and falling to the street below to escape collectors. And we see him metaphorically rise to become the “golden boy” of Zedelghem, ostensibly usurping or at least mirroring Ayrs’ position within his own household.

Finally, Frobisher leaves us with some rather serious metaphysical musings on the nature of civilization, immortality, and selfishness:

Once, [my grandfather] showed me an aquatint of a certain Siamese temple. . . . Every bandit king, tyrant, and monarch of that kingdom has enhanced it with marble towers, scented arboretums, gold-leafed domes, lavished murals on its vaulted ceilings, set emeralds into the eyes of its statuettes. When the temple finally equals its counterpart in the Pure Land, so the story goes, that day humanity shall have fulfilled its purpose, and Time itself shall come to an end.

To men like Ayrs, it occurs to me, this temple is civilization. The masses, slaves, peasants, and foot soldiers exist in the cracks of it flagstones, ignorant even of their ignorance. Not so the great…composers of the age, any age, who are civilization’s architects, masons, and priests…My employer’s profoundest, or only, wish is to create a minaret that inheritors of Progress a thousand years from now will point to and say, “Look, there is Vyvyan Ayrs!”

How vulgar this hankering after immortality, how vain, how false. Composers are merely scribblers of cave paintings.” (p. 81)

Reincarnation, immortality, the lasting impression of one man’s music a thousand years into the future…we’re going to return to these ideas in later readalong posts as we gather up more of Mitchell’s narratives and see the subtle ways they’ve been woven together. What are your thoughts so far? What do you think of Frobisher as a narrator? How reliable are his descriptions of events? Who is the exploited here? What do you think of the dreams that are appearing? What else do think about this section?

You might also like:

I love your comments on my new favorite book.

Hello. I just wanted to thank you for this series of blog posts. I had started reading the book after I’d seen (and loved) the movie, but I got stuck in the first part and was about to give up on it, when some random googling lead me to your blog and it reawakened my taste for the book. By now I’m mostly through Part 3 and good and well in love. You know the point when you know you’ll read a book to its end, well, you brought me there, and what I would have missed if you hadn’t. So, thanks a lot! 🙂

I just finished this novel, earlier today actually and I haven’t been able to do a single thing but walk around the house and think about it since. Of all the parts, this is my favorite, I love Frobisher the unstable, tortured artist… so self aware of the smokescreen of arrogance and lucky charm he throws up between his insecurities and the world, and yet blinded by it the same. Yet I always feel he’s aware even of that irony, and so can’t help be dryly sarcastic about everything else. Such a great character in the perfect setting for his voice.

I do find this chapter a bit at odds with the others, it has less to do with humanity as a whole… but maybe that’s the point. Maybe one chapter has to be dedicated to someone like Frobisher, to the way this trickling down of human nature through the centuries crystalises in art. Ayrs’ dream is possibly my favorite insert in the entire book.

I loved this part! Frobisher is such an easy to follow and funny narrator. I didn’t feel as bogged down as I did during part 1. I found him an interesting and somewhat devious character. And though I wouldn’t like him if I met him in real life, I love this type of character in literature.

I think I have officially fallen for this book now. I had to break out my sticky notes to mark all the brilliant writing. Mitchell truly has a way with words. Two of my favourites are the passage where he first meets up with Jansch. And the line about the “swampy-sheeted alligator”. I feel like this is only the beginning of the sticky notes.

Isn’t Frobisher wonderfully slippery? I picture Benedict Cumberbatch now when I read him.

I had the same experience the first time I read Cloud Atlas. Someone whose taste I trusted very much loaned me her copy and encouraged me to stick with it even though I had trouble getting into it. And then I hit part 2 and felt the pieces tumbling into place. Mitchell has absolutely gorgeous turns of phrase, which you see throughout his books. The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet (which has a somewhat similar slow start that pays off in the end) is just rife with absolutely breathtaking writing.

I love Frobisher as a narrator too. Great job David Mitchell. I’ve just finished the second half of the letters. Thank you (from Colombia) for the blog.

I’m itching to get back into the second halves now. I’ve read the book before, but on this readthrough I’m forcing myself not to skip ahead, which is sometimes difficult!

Thanks so much for your comment. I’m so pleased you’re reading along!

Frobisher is fascinating because his entire section of the book is the viewpoint of a predator. We get some view-point sections from predatorial characters later on (in the convoluted Luisa Ray Mystery), but nothing so clear as that of Frobisher.

After reading Part Two, the sections when he contemplates Ewing’s letters drip with irony. He immediately recognizes that Ewing is being exploited by his “benefactor”, but doesn’t recognize that Ayers is doing the same thing to him. He’s just so arrogant and self-absorbed that he can’t see it.

I love how self-absorbed he is. He genuinely doesn’t seem to have a second thought about stealing books, and he doesn’t see the truth about how he’s reacting to Eva. He’s truly the mastermind of his destiny in his own mind. He’s tripped through life so far and managed to escape mostly consequence-free so his own rakishness has been reinforced to him.

Discussing this section is almost maddening, because Frobisher Part Two completely up-ends a ton of your expectations about what is actually going on. I remember being in awe when I was reading it.

And that subversion of expectation after making you hold your memories of the story through so many other parts, I think, is really a key part to the genius of the book. Mitchell does so much with structure and intertextuality, and I think it’s very deliberate that we take left turns after having been away from a particular story for so long.

I think Frobisher is a great narrator, although we are only getting one side of the story. I was smiling to myself as I reading this section and internally shaking my head at the same time. This readalong is a great idea. Looking forward to the next installment.

I love Frobisher as a narrator. He’s a self-involve amoral (or immoral?) prig entirely too pleased with his own genius, which makes him such fun to read. He reminds me of Sherlock Holmes (particularly the Benedict Cumberbatch version) or Sirius Black or Eden Bellwether from The Bellwether Revivals.

Thanks very much for joining the readalong! Can’t wait to hear further thoughts from you 🙂

I see it as mutual exploitation. Each person gaining something. I also see Frobisher as an amoral individual despite his obvious gifts. An unrepentant hypocrite-passing judgement on Eva. That being said-I find him much easier to “accept” than Adam Ewing as a narrator.

Thanks for stopping by! That’s a good point–a relationship isn’t always (or possibly even often) just about one person exploiting the other. Each person is benefiting and taking from the other in the case of Frobisher and Ayrs.

I really enjoy Frobisher’s harsh, snarky judgements of Eva, because he doesn’t seem to have any idea how hypocritical he’s being.or that he’s quite clearly infatuated with her.

Because of the nature of this part, all in letters, I find there to be a deeply personal intimacy at play here, and this was one of the sections I had real trouble keeping myself from flipping through the book for, to find the missing half and see what happens.