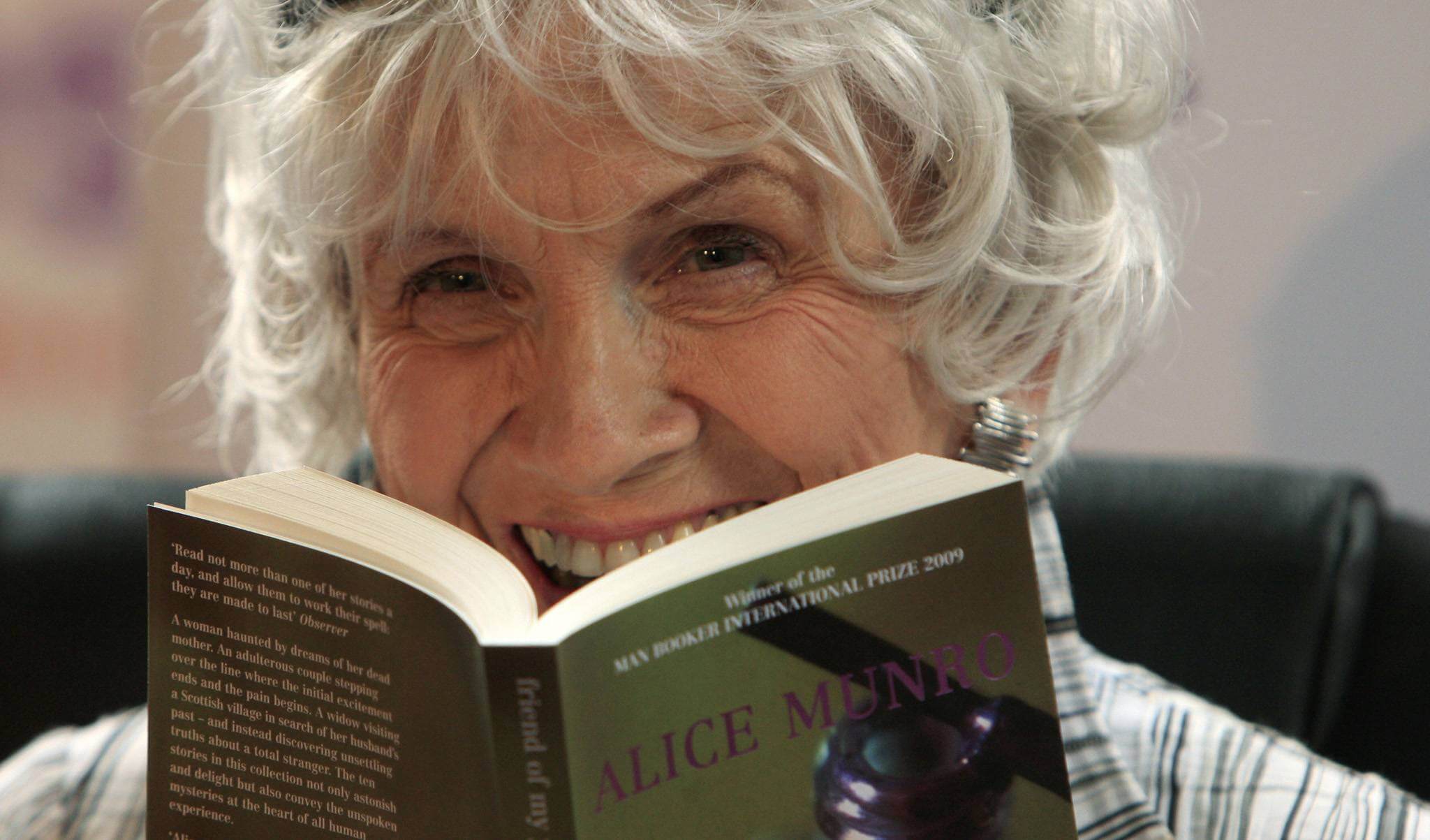

On the evening of November 2nd, 2013, a sold-out crowd at the International Festival of Authors rose in a standing ovation at the urging of editor extraordinaire Douglas Gibson, who asked us to “hoot, and holler, and clap our hearts out” so that Alice Munro could hear us all the way in Victoria, BC, where she’s wintering with her daughter. The Fleck Dance Theatre was packed to the rafters, and we were all on our feet, shouting out our love and admiration for the divine Ms. Munro.

Alice Munro has been a quiet giant of the Canadian and international literary landscape for decades, publishing short fiction that reverberates with authenticity about lives, journeys, small towns, and the roles women play. On August 1st (two months before Ms. Munro became the first Canadian ever to win the Nobel Prize for literature), IFOA announced a tribute to her, a “‘who’s-who’ of Canada’s literary community, including other writers, close colleagues and family members, as they present readings of Munro’s work.” From newer works such as Dear Life and Too Much Happiness to canonical classics Lives of Girls and Women and Runaway, Ms. Munro’s short stories have been a touchstone and a revelation to me—and to many others. The promised who’s-who brought a thrilling mix of authors to the stage: joining host Gibson was Jane Urquhart, Miriam Toews, Colum McCann, Alistair MacLeod, and Margaret Drabble.

Each esteemed author shared anecdotes of Alice, including personal encounters and friendships and her influence on their writing. Each spoke about a different aspect of her work and each read from a different story. Douglas Gibson was a charming host, offering jokes and insights from his long association with Munro: he has been her editor for decades, and she followed him from MacMillan to McClelland & Stewart in order to keep working with him.

Jane Urquhart (Away, Sanctuary Line) read first from a novel written by Alice’s father, Robert Laidlaw, a scene about a family of settlers in rural Ontario, and then from a story Alice had written about her the Laidlaws, examining the way both generations of writers were bound to the land of Huron County. She also brought with her her own diary from the 1980s, which details her fannish glee at meeting Alice: “I met Alice Munro today—four exclamation marks.” They spent a whole day together, and the conversation never ceased flowing. “She told me that she had heard a rumour,” Urquhart finished, grinning up from her old diary, “that the Clinton librarian was once abducted by Albanians.” Alice wondered if she could turn that into a short story. “I hope she does—seven exclamation marks!”

Up next was Miriam Toews (A Complicated Kindness, Irma Voth), whom Douglas Gibson introduced as a member of the writing generation who grew up in Munro’s shadow “and found the shade not depressing, but inspiring.” Toews talked about her childhood in rural Manitoba and, at age 12, sneaking into the bedroom of her older sister, who was away at university. There she found Lives of Girls and Women, which she read in great secrecy, swiftly returning it to its place on the shelf when she heard her parents coming home and throwing herself in front of the TV like she’d been there the whole time. This was “serious, badass, hardcore adult literature,” Toews mused, and she remembered thinking, “Well, this sure changes things, doesn’t it.”

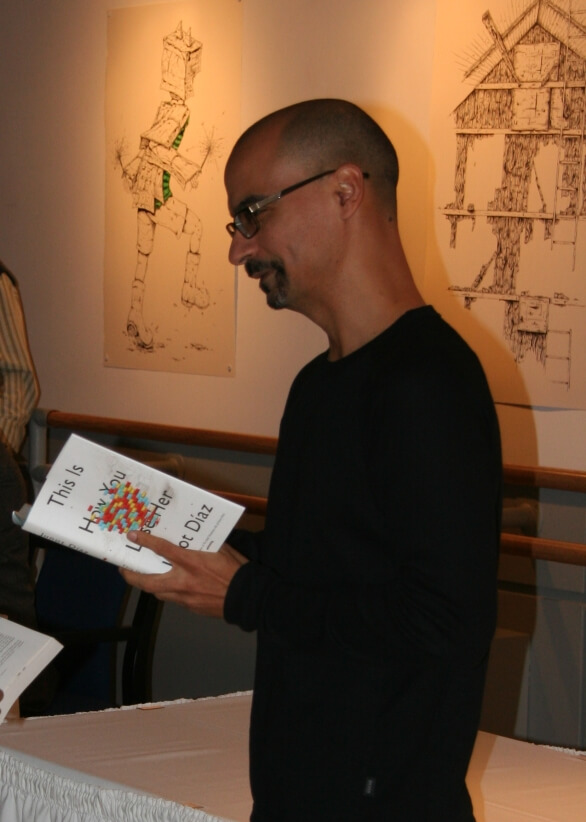

Colum McCann (Let the Great World Spin, Transatlantic) took his place on the stage, joking that he once asked a Russian why they’re so good at short stories, and was told “we have so little time between arrests.” For the Irish like himself, he continued, short stories are best because you get them out between weekly confessions. “So what’s the story on you Canadians?!” he wondered. McCann mused on the short story form, describing it as not fundamentally different from longer fiction: “they’re both universes,” but a novel is an exploding universe, moving outward in all directions, while a short story is imploding, becoming focused, “a white hot star.” In the case of Alice Munro’s short stories, “nothing is simple, especially the apparent ease of simplicity.” McCann read from “The Bear Came over the Mountain,” the poignant, difficult source material for Sarah Polley’s acclaimed 2006 film Away from Her about a man struggling to cope with his wife’s Alzheimer’s. “Here is one of those Alice Munro shotgun moments,” he said with a twinkling smile before reading from the jarringly good ending.

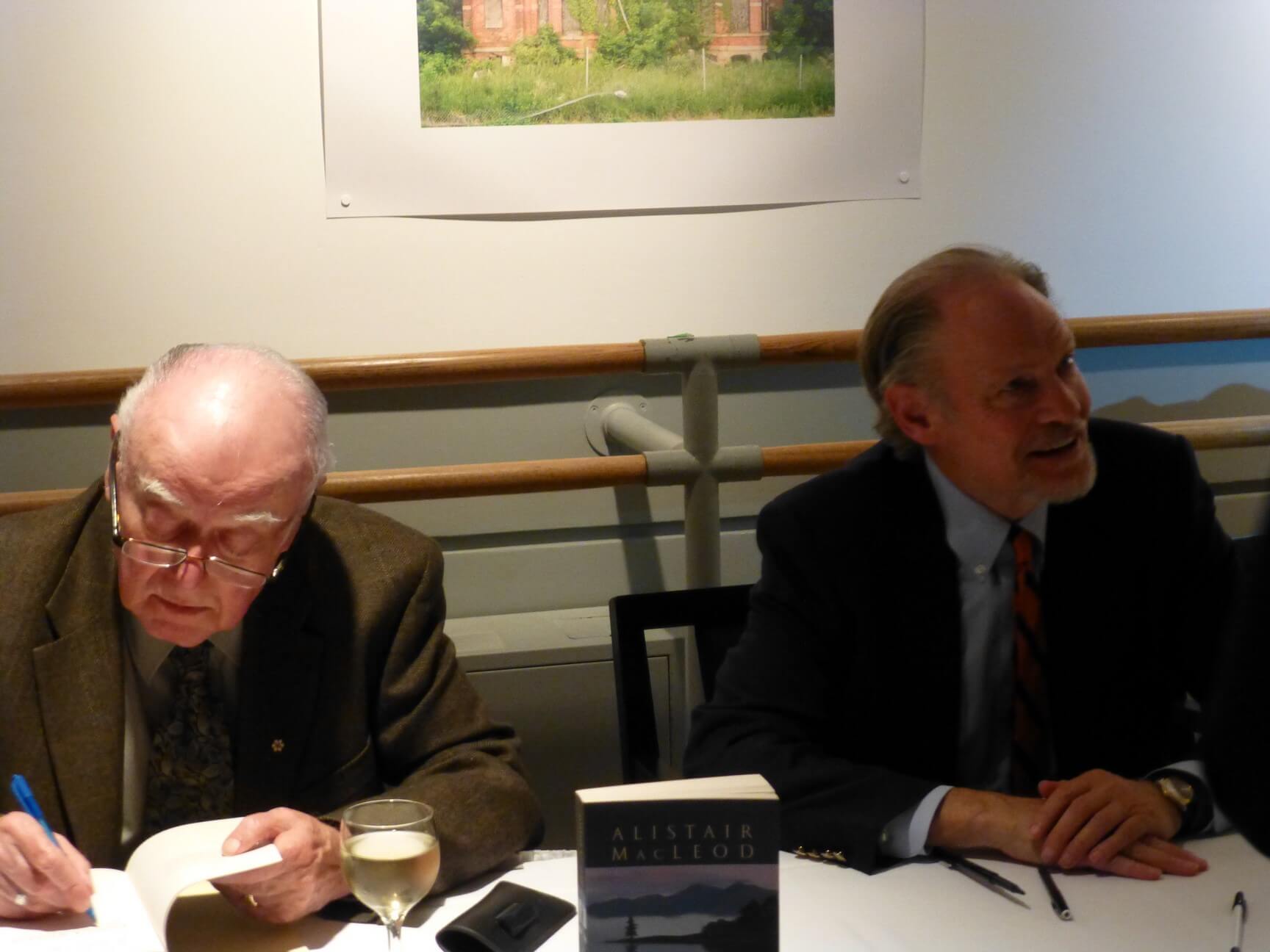

Allistair MacLeod (No Great Mischief, The Lost Gift of Salt and Blood) came next, after being introduced by Douglas Gibson as “the Stone Carver”—a joke about his glacial rate of production (and perhaps a nod to Urquhart’s The Stone Carvers). “I want to talk to you about detail,” MacLeod said to the crowd, discussing with gravity and humour the importance of detail, of noticing which pair of earrings the waitress is wearing that day, that Munro exhibits in her works. Some people can observe, and some people cannot observe, he said. Alice can observe. She gives great details on estuaries, he exclaimed, and the importance of the geography in her works can’t be overemphasized. He read from one of my favourite stories, “Passions,” choosing what he called “a very Alice Munro-y passage.” “You see?” he asked afterward. This character was “an Alice Munro girl: super smart, but poor,” someone who wants to learn all she can but is at the mercy of her geography and her poverty, who maybe has to rely on an unreliable boy to get a ride to the dance in town on Saturday night. “[Alice] notices everything,” he concluded, “and she urges us to notice everything, and I’m glad you’re here tonight because you notice everything!”

The final guest of the night was the British Margaret Drabble, who confided “Alice is a very important part of my Canadian experience.” Rereading Munro in preparation for a Canadian visit is just as rewarding as reading her for the first time. She recalled hearing the news of Alice’s Nobel win: “I let out a great cry of joy,” which her husband heard from floors away and came racing to help, assuming “something ghastly” had happened in the kitchen.” Beaming a the crowd, Drabble praised “her Wordswordian faith in the interestingness of everyday people. . .her insight, her sympathy, and her great wit.” Like MacLeod, she spoke of the importance of geography in Munro’s work, particularly of the deeply Canadian landscapes and journeys she evokes: “She brings Canada itself to life,” exploring “lives rooted and lives vagrant…not a romantic, but most powerful sense of the way the land shapes our lives.”

At the end, we all rose again to applaud the fine gather of wonderful guests and, of course, Alice Munro herself. I hope she heard the words of admiration spoken that evening. I hope she felt how much that packed house loves her.

You might also like:

Wow – sounds like a spectacular evening! Lucky you 🙂

Thanks! Such a perfect evening, filled with affection and admiration for Alice.