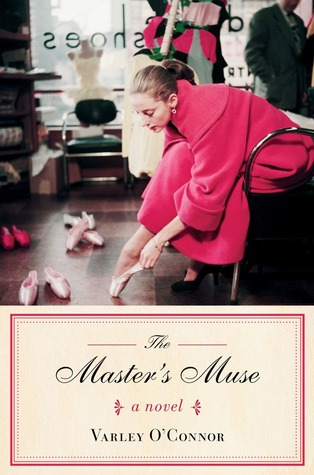

The kinetic world of ballet dancers and the artistic innovation of the 1950s American dance scene are the backdrop of The Master’s Muse, by Varley O’Connor. This novelization of real events is told through the first-person perspective of Tannaquil Le Clercq, prima ballerina of the nascent New York City Ballet, and the fifth wife of superstar choreographer George Balanchine. Tanaquil’s story is not just that of a ballerina, however; in 1956, during a European tour, Tanaquil contracted polio, which resulted in the paralysis of her lower body.

“Pain dilutes in the extension of time. Like ink in water it blackens, and then the water stays clear and the blackness whirls. Days come when it’s a single black thread swirling about. there it is. Hello. There you are.”

The kinetic world of ballet dancers and the artistic innovation of the 1950s American dance scene are the backdrop of The Master’s Muse, by Varley O’Connor. This novelization of real events is told through the first-person perspective of Tannaquil Le Clercq, prima ballerina of the nascent New York City Ballet, and the fifth wife of superstar choreographer George Balanchine. Tanaquil’s story is not just that of a ballerina, however; in 1956, during a European tour, Tanaquil contracted polio, which resulted in the paralysis of her lower body.

Tanny grew up in the school run by Balanchine, who noticed her prodigious talent early. She is the prototypical “Balanchine dancer,” the right sized head and long legs, the ability to travel and “eat space” on the stage, perfect technique and passion. At what point the artistic relationship turns into love is unclear but it does happen early; Tanny is already in love with Balanchine in her early twenties, when he was still married to his fourth wife, Maria Tallchief. Each of Balanchine’s wives was, at the time of marriage, his principal female dancer. She becomes the fifth Mrs. Balanchine when she is twenty-three and he is forty-eight.

But this is all prologue. The real story opens in Copenhagen, after Tanny and George have been married for several years, and Tanny is already noticing that George’s attention is wandering. Though the marriage is rocky, Tanny is at the peak of her physical and artistic career. She is stunningly beautiful, appearing on the cover of Vogue magazine, and she is sought after by choreographers who create dances for her. In Copenhagen, she thinks she is becoming a bit ill, feeling weak and seeing some swelling in her thigh, but she dances through the pain. The flu, she thinks, until she realises that she can’t move her legs. She was twenty-seven years old.

Admitted to the hospital and diagnosed with polio, the first part of the book concerns Tanny’s battle with the disease. She describes her boredom, fear, and anger, her terror of the iron lung and the immediate ease of breathing she feels when she is placed inside it. She lives for letters from her dear friend and once-lover Jerome Robbins, the famed director and choreographic yin to Balanchine’s yang. Balanchine stays by Tanny’s side throughout her hospitalization, the love that grew between them through movement and dance renewed in Tanny’s stasis.

The second half of the story follows the Balanchines’ lives after Tanny’s recovery in Warm Springs, a polio rehabilitation clinic wherein Tanny and George apply all of their collected experience in physical training to reteaching Tanny’s body to move. While some “traces” of nerve response are enough to allow her to condition her upper body into movement, she never regains the use of her legs, and must spend the rest of her life in a wheelchair. We see their marriage through the good times, as they readjust to life without movement: the dinner parties, the summer house, Tanny’s writing projects, the discussions of choreography and the dance world. And we see the marriage disintegrate, as rumours of Balanchine’s dalliances with other dancers abound, ending in his inevitable obsession with a new dancer.

The Master’s Muse follows in the recent trend of books such as Paula McLain’s The Paris Wife, about Ernest Hemingway’s wife Hadley. The narrative choice–to “novelize” a real life, and to tell the story in the first person, is an interesting one, bringing about an immediate authenticity to the narrative but also making for a somewhat unreliable narrator: we know only Tanny’s perspective here, and we see only what she knows or will allow herself to know. She is a proud, reserved character, and is sometimes difficult to connect with. This style of narration also demands rigorous research in order to create the voice and emotions of a real person. O’Connor does a beautiful job in showing the diverse personalities of the 1950s and 1960s dance scene. Balanchine’s enigmatic presence, his strengths and his follies, are rendered in a complex portrait of a difficult, gifted man. Tanny herself is a picture of struggle in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. She never sees herself as a martyr and despises being thought of as “a polio,” refusing to be defined by the disease that ripped away her career.

This is also an excellent presentation of a time in dance history that’s been somewhat gentrified in history. We tend to think of Balanchine as old-school, one of the great choreographers and a standard of many companies’ repertoires, but at the time, he was cutting edge. His long movements, his use of flexed feet and interesting angles of arms and legs, his “storyless” ballets at a time when storybook ballets were the thing, were all groundbreaking. It’s strange to think of the 1950s as the time of “cool,” of artistic reinvention, of Balanchine bringing ballet to the masses and making it hip. As the story sweeps into the 60s and 70s, Balanchine grows older and more sentimental, and artistic trends shift, leaving him dancing with that dangerous partner, obsolescence. this mirrors Tanny’s own fight to remain relevant, and her life choices and the path of her own career post-polio is deeply intriguing.

Tanny’s relationships with her mother and with her father, with Jerry Robbins, and with her female friends, are all three-dimensional. The central relationship of Balanchine and Tanaquil is at the heart of the story, both during their marriage and after it. They love each other to the very end, even after their divorce. Tanny’s love is intense and somewhat irrational, and yet is portrayed sympathetically. They are bound to each other, even as they grow apart. And Balanchine’s womanizing is treated in a fairly forgiving way: he is in love with movement, Tanny observes; the physical, moving female is sensuality to him, and he cannot dissociate his loves from his dances. His adoration of young women is given far more of a pass than if he were, say, a sixtysomething accountant who had a thing for 18-year-old girls.

For those who are interested in the dance world, seeing characters such as Balanchine, Jerry Robbins, Igor Stravinsky, and the dancers of the New York City Ballet come to life is truly magical. This book is a treat for dance lovers, letting us peek inside rehearsals and performances, and the society that is professional dance. One particularly sweet passage refers to the problem with stage moms, apparently creatures who have been around since time immemorial:

Mama Toumanova wore each new pair of Tamara’s slippers herself, tromping about, softening them so her daughter wouldn’t get hurt. Mama stood in the wings and called, “Four pirouettes, Tamara!” Yes, my mother, Edith, came on tour with us far too often and watched every one of my performances, but she wasn’t that bad. She even laughed at the sign on the dressing room door of the corps in New York at City Center, NO MOTHERS ALLOWED.

And yet in spite of all this, there is something of a lack of depth, or analysis, that is perhaps part of the first-person narrative. While authentic, the emotional heart is a bit cold. Perhaps this is because Tanaquil in real life was an intensely private person, and as the main character and narrator of the book, her emotions are often kept in check even as she deals with great difficulty.

Further, I would imagine the insider references to the various real-life characters creates a somewhat inaccessible framework for the casual reader who doesn’t have some preexisting knowledge of dance and its history in the United States. Little explanation is given for who anyone is, or what some of the dance terminology means. There is an assumption of prior knowledge that shuts out the wider audience.

And finally, a small nitpick about the production of the book: I’m not sure why there aren’t any photographs included. Surely images of Tanaquil dancing with Jacques D’Amboise or Arthur Mitchell, with Jerry Robbins or Balanchine himself, perhaps reproductions of her fashion magazine photo shoots, would help contextualize this true-life story.

If you are a ballet fan, this book is absolutely worth the read. The insider’s peek into this major part of American dance history is fascianting, as is the difficult relationship between Tanaquil and George. If you are not a lover of dance, however, this may not be the book for you, lacking the emotional depth and accessibility to make it a truly universal story.

Three out of five blue pencils

The Master’s Muse, by Varley O’Connor, published in Canada by Scribner, © 2012

Available at the Simon & Schuster website, Amazon, Indigo, and fine independent bookstores everywhere.

7 thoughts on “The fifth Mrs. Balanchine: A review of The Master’s Muse by Varley O’Connor”